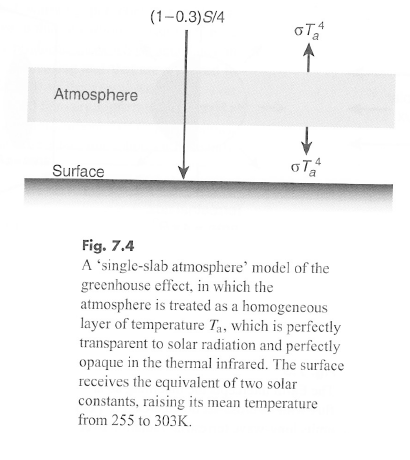

In Part One we saw how a very simple energy balance model with some very basic assumptions provided some insight into how the surface and atmospheric temperatures are determined.

We assumed that the atmosphere was transparent to solar radiation (radiation less than 4 μm), that the atmosphere was totally opaque to terrestrial radiation (greater than 4 μm), and that the atmosphere was isothermal (all at one temperature).

All of these assumptions are incorrect.

We derived an average surface temperature of 303K – instead of the realistic 288K – from this simple energy balance model.

In this article we will look at a very basic model to estimate the temperature of the stratosphere. If you aren’t clear about the troposphere/stratosphere, take a look at Tropospheric Basics. For caveats and explanations about simple models, and about radiation and emissivity, please check Part One.

In the troposphere, heat transfer is dominated by convection. The atmosphere transitions to what we call the stratosphere when convection ceases because radiation becomes more effective for moving energy. The atmosphere progressively thins out the higher we go – and as a necessary consequence it becomes optically thinner (note 1). This also implies that the temperature in the stratosphere will not vary significantly with height because radiation can transfer energy across large distances.

In practice, absorption of solar radiation by ozone means that the stratospheric temperature increases with height. However, in this simple model we want to make huge assumptions just to see what results we get, and in this model we continue to assume (incorrectly) that the atmosphere is totally transparent to solar radiation.

Here is an extract from Elementary Climate Physics by Prof. F.W. Taylor.

It is another very simple model:

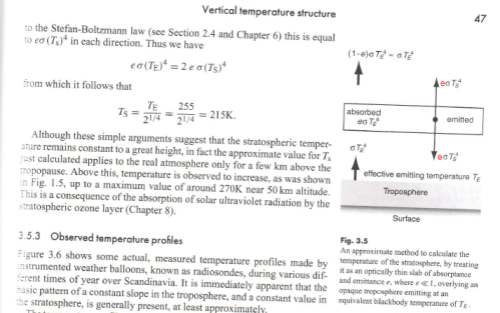

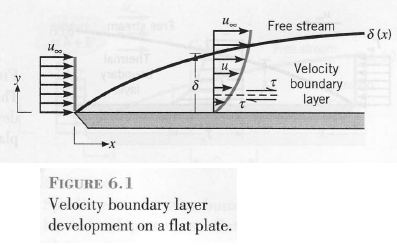

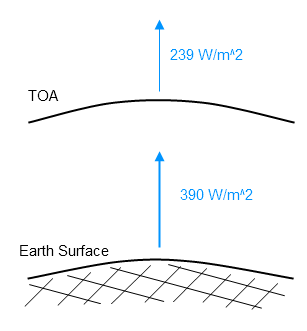

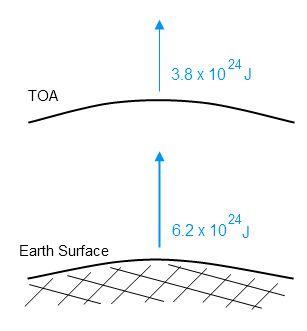

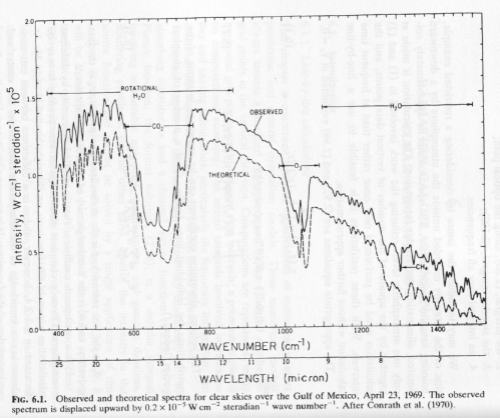

Figure 1

Note there there is a correction (in red) to the diagram (his fig 3.5). Even Professors of Physics make mistakes (or their editors do).

If you followed the method of calculation in Part One then this won’t be too difficult.

We know that the earth/troposphere emits to space at an “effective radiating temperature” of 255K. This term effective radiating temperature causes a lot of confusion. It is convenient shorthand for the temperature at which a blackbody would be to radiate that flux. It doesn’t mean that blackbodies exist – perish the thought. And it doesn’t mean that anyone is assuming that the atmosphere is radiating as a blackbody.

What it means is that the earth/atmosphere emits 239 W/m² to space. We call that an “effective radiating temperature” of 255K. It’s not meant to upset anyone. If we wanted we could just call it 239 W/m². We will do that later just to see the effect.

And following Part One, with the assumption of an optically thick surface/troposphere (read about “optically thick” in that article), we have the emission of surface radiation:

E = σTE4

where TE is the average emitting temperature of the surface/troposphere (as if it was a blackbody)

And if we make some assumptions about the optical properties of the stratosphere we might find some approximate answers that are interesting.

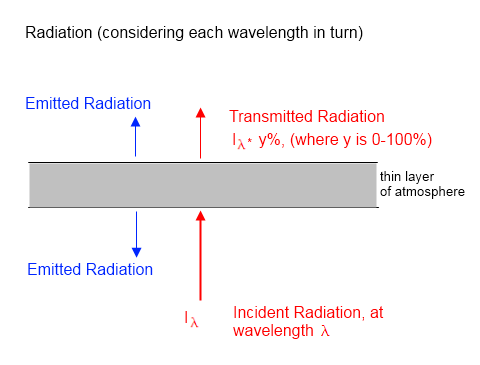

We assume (incorrectly) that the stratosphere is an isothermal layer at temperature, Ts. We assume that the stratosphere is optically thin so that the emission from the surface/troposphere is approximately equal to the emission to space.

The stratosphere has an emissivity, ε, which is very small.

From Kirchhoff’s law, emissivity = absorptivity for the same wavelength ranges. We will come back to review this assumption a little later, but for now note that if the surface/troposphere and the stratosphere are at similar temperatures then this assumption:

absorptivity of stratosphere for surface/troposphere radiation = emissivity of stratosphere

– is approximately correct.

Therefore, from energy balance considerations, the energy absorbed by the stratosphere must be the energy emitted by the stratosphere. So, from figure 1:

εσTE4 = 2εσTs4

therefore:

Ts = TE / 21/4 = 215 K

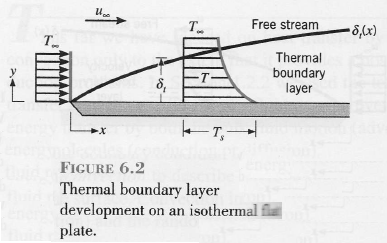

Now, surprisingly enough for such simple assumptions, this is a reasonable value for the temperature at the bottom of the stratosphere.

Without “Effective Radiating Temperatures”

Let’s redo the calculations – this time using the actual flux to space from the surface/troposphere instead of the “effective radiating temperature”.

The surface/troposphere radiates (globally annually averaged) 239 W/m². The stratosphere absorbs a small fraction of this, determined by absorptivity = emissivity = ε:

ε x 239 = 2εσTs4

therefore:

Ts = (239/σ)1/4 / 21/4 = 215 K

The value is the same as previously calculated, no surprise to anyone who has got to grips with this subject.

Using Kirchhoff

Earlier we used the fact that absorptivity = emissivity for the stratosphere, because of Kirchhoff’s law.

It is very important to understand how to use this law correctly. An excellent example of how not to use it was done by Martin Herztberg in his paper, Earth’s Radiative Equilibrium in the Solar Irradiance, Energy & Environment (2009).

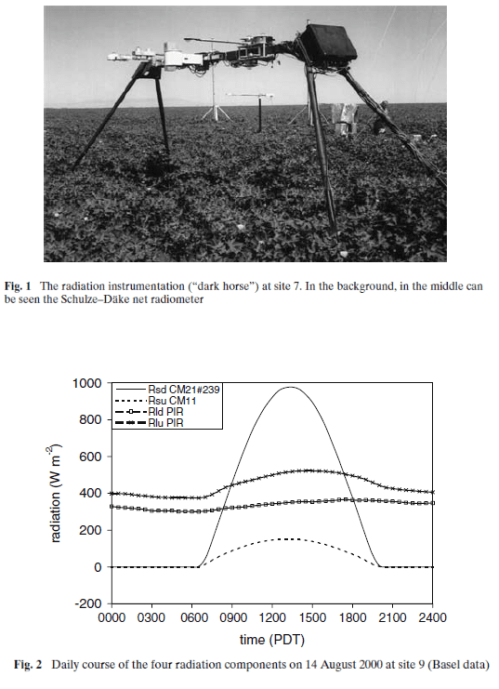

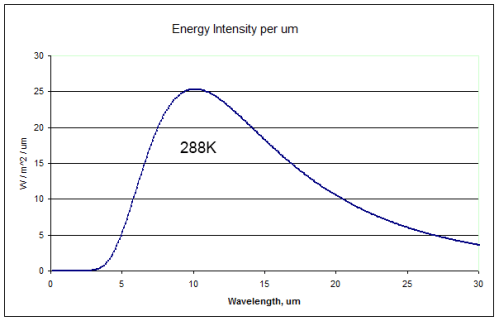

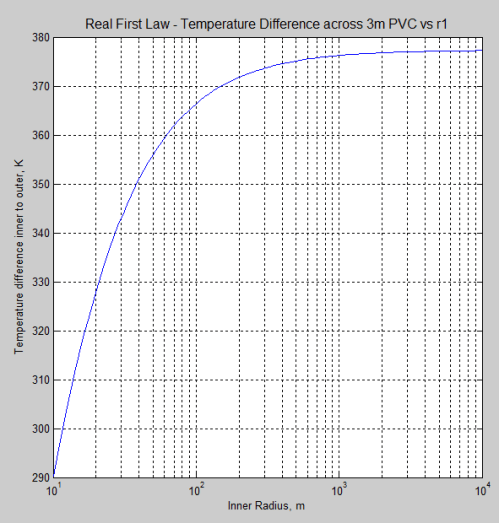

Let me paint a picture with some graphs.

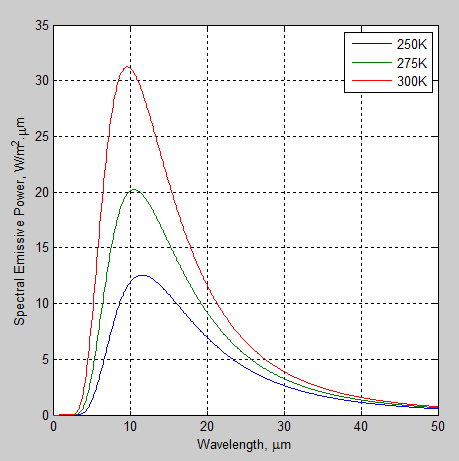

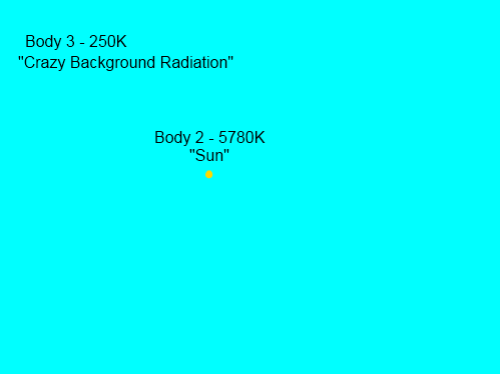

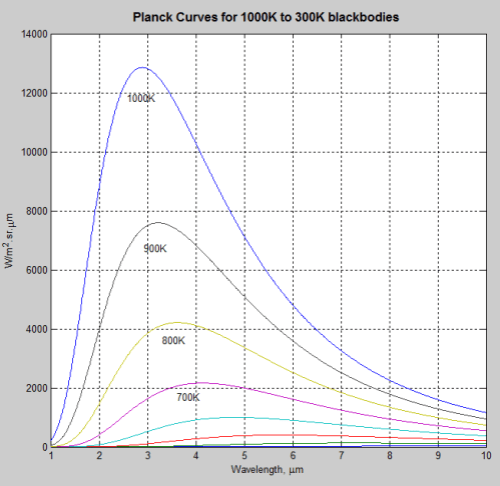

First, the wavelength dependence of blackbody radiation for three different temperatures. Remember that blackbody radiation is just a “perfect emitter”, or the “gold standard” of radiation. Real bodies cannot radiate at a higher intensity at any wavelength, although many come close.

The solar radiation has been normalized to the value at the earth’s surface (because it’s a long way from the sun to the earth – check out The Sun and Max Planck Agree – Part Two):

Figure 2

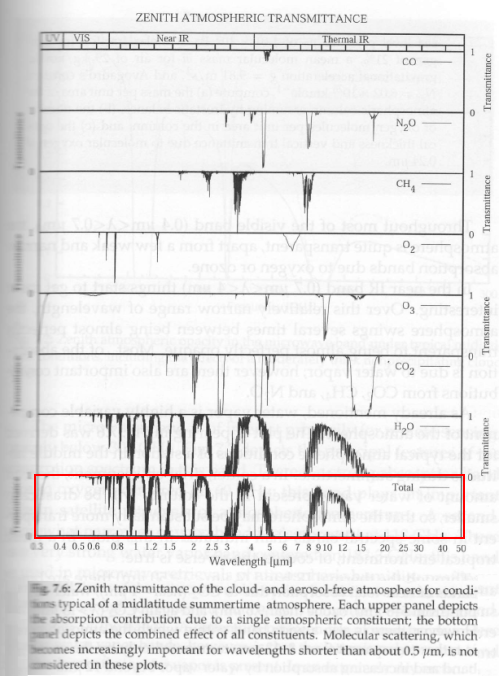

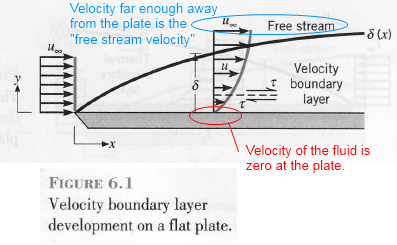

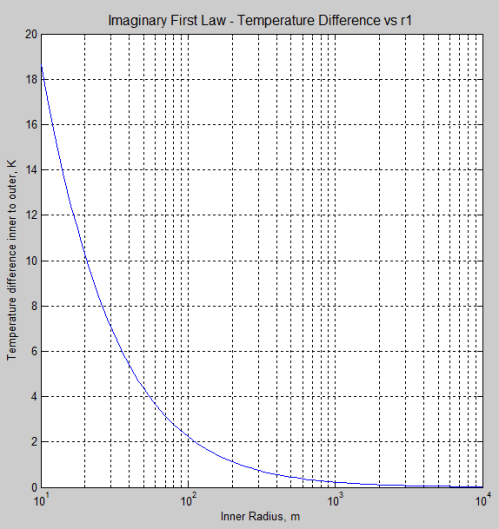

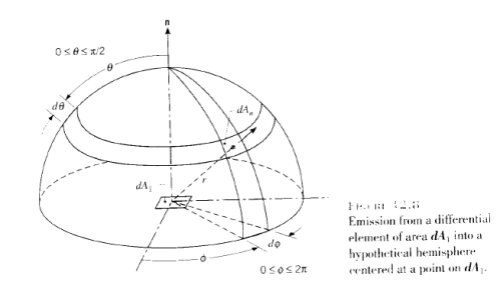

Now, the transmittance for the atmosphere as a function of wavelength. For 4μm and longer wavelengths, absorptance = 1 – transmittance. For shorter wavelengths, especially below 0.5 μm, scattering becomes significant, which means that absorptance = 1 – transmittance – reflectance.

In any case, what should be clear is that absorptance is a strong function of wavelength. See the red marked graph at the bottom:

Figure 3

At any given wavelength, absorptance = emissivity.

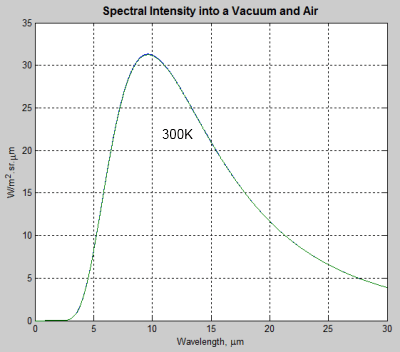

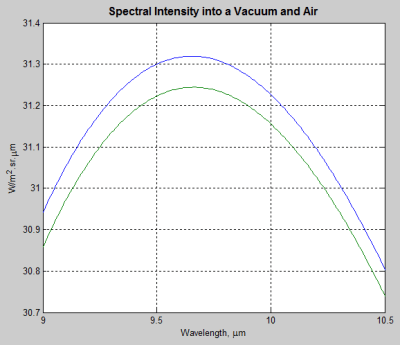

So let’s consider the case of a 255 K atmosphere absorbing solar radiation.

The solar radiation is the blue curve in figure 2 – so to calculate how the atmosphere/surface absorbs this radiation we can use the absorptivity (≈ 1 – transmissivity) between 0-5 μm.

The surface/troposphere radiates according to the green curve. We need to multiply this curve by the emissivity = absorptivity at these wavelengths.

So although absorptivity (at a given wavelength) = emissivity (at a given wavelength), it isn’t much use if the source of the incident radiation is at very different wavelengths from the emission. Which is why Martin Herztberg hasn’t passed the competency test in this field. A “rookie mistake”.

You should be able to see from figure 2 that although the surface/troposphere and stratosphere are at different temperatures, an average absorptivity value for absorbing radiation at 255 K will be quite similar to the emissivity value for emitting radiation at 215K.

If we wanted accurate results we would need to use the absorptivity at the relevant wavelength and the emissivity at the relevant wavelength. We also would not assume that the stratosphere was isothermal, or that it was perfectly transparent to solar radiation.

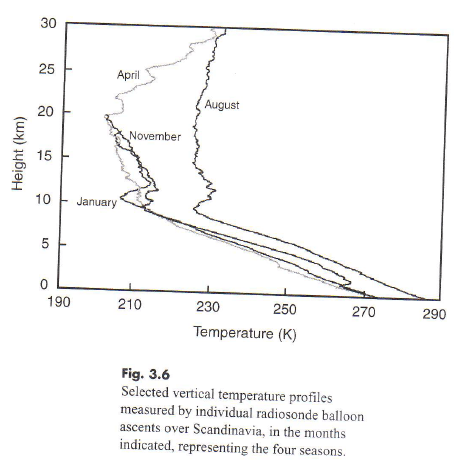

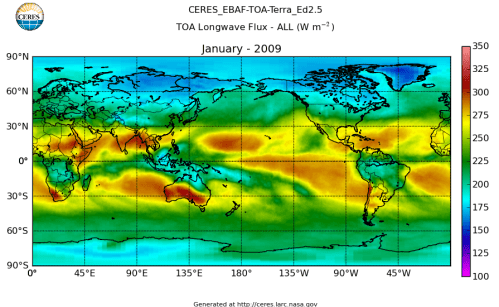

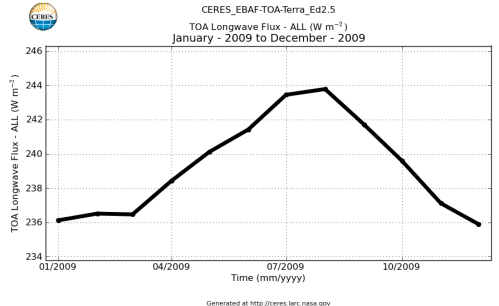

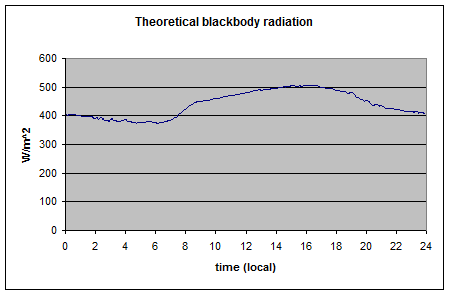

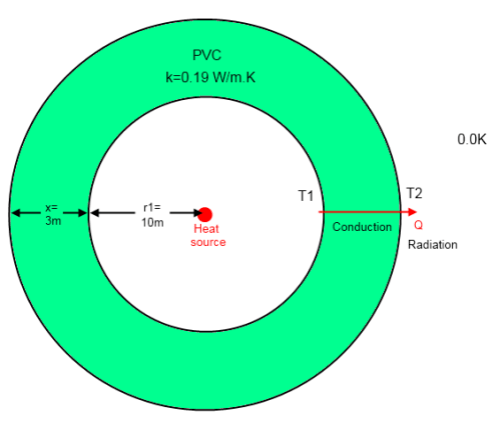

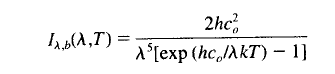

By the way, here are some temperature measurements of the stratosphere in one location:

Figure 4

Conclusion

Calculating the temperature of the stratosphere is a difficult problem. However, as in many fields of scientific endeavor, we can make a very simple model and see how the results compare with reality (and the results of more complex models).

In the example here we make some very simple assumptions and find a result for the stratospheric temperature which is not too far off the mark. However, the only reason for producing (reproducing) this model was to help newcomers to the field gain a conceptual feel for the basics of energy balance and radiative transfer.

By the way, as explained in Part One, no one in climate science believes that the assumptions for this model are correct. Everyone knows that the atmosphere is not a blackbody (perfectly opaque) for all wavelengths greater than 4 μm, and is not perfectly transparent for all wavelengths less than 4 μm.

Notes

Note 1: Optical thickness is proportional to the number of absorbers (molecules that absorb radiation) in the path. So as the atmosphere thins out the density reduces and, therefore, the optical thickness must also reduce. You can read more about the equations of optical thickness in Understanding Atmospheric Radiation and the “Greenhouse” Effect – Part Six – The Equations

Find Stuff Out and Book Reviews

Posted in Basic Science, Commentary on February 26, 2011| 200 Comments »

Reading one good text book on climate science can save 100’s of hours of reading rubbish on the internet. And there is a lot (of rubbish). Well-meaning people without the baggage of any knowledge of the subject writing rubbish, then repeated by other well-meaning people.

Text books cost money. But depending on which country you live in and whether you have an income, the “payback” means that not buying it is like working for $1/hr. That assumes reading rubbish isn’t a hobby for you..

And depending on where you live you can often join a university library as an “outsider” for anything ranging from $100/year up – and borrow as many books as you like.

Learning can be like a drug. In which case, other justifications aren’t necessary, you have to feed the habit regardless. So pawn family jewelery, sell your furniture, etc. Well, as an addict you already know the drill..

Just some ideas.

Global Physical Climatology – by Dennis Hartmann

Academic Press (1994)

Amazon for $88 (reduced from $118, the price at the normally amazing bookdepository.co.uk).

Why am I recommending such an old book? This covers the basics very thoroughly. When someone covers a lot of subjects there is inevitably a compromise. To cover each of the subjects “properly” would be 4,000 pages or 40,000 pages – not 400 pages. What I like about Hartmann:

a) very readable

b) very thorough

c) enough detail to feel like you understand the basics without drowning in maths or detail.

Maths is the language of science, and inevitably there is some maths. But without any maths you can still learn a lot.

Now, a few samples..

From Chapter 4:

From chapter 11:

As you can see, there is some maths, but if you are maths averse you can mostly “punch through” and still get 80% instead of the full 100%.

Elementary Climate Physics by Prof. F.W. Taylor

Oxford University Press (2005)

bookdepository.co.uk for $44 with FREE shipping lots of places in the world, unbelievable but true.

Amazon has it for $60 plus shipping.

This is an excellent book with more radiative physics than Hartmann, but also more maths generally. For example, in the derivation of the lapse rate there is some assumed knowledge. That’s par for the course with textbooks. They are written with an audience in mind. The audience in mind here is people who already have a decent knowledge of physics, but not of climate.

However, even with a tenuous grasp of physics you will get a lot out of this book. Here’s the downside though – quite some maths:

Well, he is teaching physics.

A First Course in Atmospheric Radiation – Grant Petty

Sundog Publishing 2006

Amazon from $48

Thanks to DeWitt Payne for recommending this book, which is excellent. This is the best place to start understanding radiation in the atmosphere. Goody & Yung 1989 is comprehensive and detailed – but not the right starting point.

Radiative physics is no walk in the park. There is no way to make it astoundingly simple. But Petty does a great job of making it five times easier than it should be:

Now onto “not climate science”:

An Introduction to Thermal Physics – Daniel Schroeder

Published by different companies in different countries.

Amazon from $45 plus shipping and Bookdepository for $56 free shipping.

A book that is nothing to do with climate science, but quite brilliant in explaining very hard stuff – heat and statistical thermodynamics – so it sounds really easy. Not many people can explain hard subjects so they sound easy. Most textbooks writers make slightly difficult stuff sound incomprehensible until after you understand it – at which point you don’t need the textbook.

It wasn’t until I read this book that I realized that Statistical Thermodynamics was actually interesting and useful.

The Inerrancy of Textbooks?

Are textbooks without error and without flaw?

So what’s the point then?

The people who write textbooks usually have 20+ years of study in that field behind them. And until such time as E&E start a line of textbooks, the publishers of textbooks, with their own reputation to protect, only ask people who have a solid background in that field to write a textbook.

So even if you are intent on demonstrating that climate science has no idea about basic physics – how are you going to do this?

You could follow the path of many other brave bloggers and commenters who write about the “paltry understanding” of climate science without actually knowing anything about climate science.

But if you choose to do it the old-fashioned way then you should at least find out what climate science says.

Read Full Post »