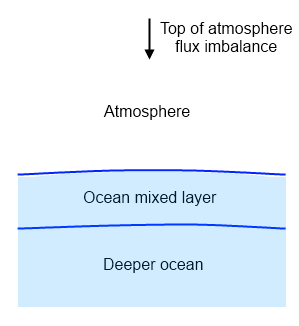

In the last article we had a look at the depth of the “mixed ocean layer” (MLD) and its implications for the successful measurement of climate sensitivity (assuming such a parameter exists as a constant).

In Part One I created a Matlab model which reproduced the same problems as Spencer & Braswell (2008) had found. This model had one layer (an “ocean slab” model) to represent the MLD with a “noise” flux into the deeper ocean (and a radiative noise flux at top of atmosphere). Murphy & Forster claimed that longer time periods require an MLD of increased depth to “model” the extra heat flow into the deeper ocean over time:

Because heat slowly penetrates deeper into the ocean, an appropriate depth for heat capacity depends on the length of the period over which Eq. (1) is being applied (Watterson 2000; Held et al. 2010). For 80-yr global climate model runs, Gregory (2000) derived an optimum mixed layer depth of 150 m. Watterson (2000) found an initial global heat capacity equivalent to a mixed layer of 200 m and larger values for longer simulations.

This seems like it might make sense – if we wanted to keep a “zero dimensional model”. But it’s questionable whether the model retains any value with this “fudge”. So because heat actually moves from the mixed layer into the deeper ocean (rather than the mixed layer increasing in depth) I instead enhanced the model to create a heat flux from the MLD through a number of ocean layers with a parameter called the vertical eddy diffusivity to determine this heat flux.

So the model is now a 1D model with a parameterized approach to ocean convection.

Eddy Diffusivity

The concept here is the analogy of conductivity but when convection is instead the primary mover of heat.

Heat flow by conduction is governed by a material property called conductivity and by the temperature difference. Changes in temperature are governed by heat flow and by the heat capacity. The result is this equation for reference and interest – so don’t worry if you don’t understand it:

∂T / ∂t = α . ∂²T / ∂z² – the 1-d version (see note 1)

where T = temperature, t = time, α = thermal diffusivity and z = depth

What it says in almost plain English is that the change in temperature with respect to time is equal to the thermal diffusivity times the change in gradient of temperature with depth. Don’t worry if that’s not clear (and there is a explanation of the simple steps required to calculate this in note 1).

Now the thermal diffusivity, α:

α = k/cpρ, where k = conductivity, cp = heat capacity and ρ = density

So, an important bit to understand..

- if the conductivity is high and the heat capacity is low then temperature can change quickly

- if the conductivity is high and the heat capacity is high then it slows down temperature change, and

- if the conductivity is low and the heat capacity is high then temperature takes much longer to change

Many researchers have attempted to measure an average value for eddy diffusivity in the ocean (and in lakes). The concept here, an explained in Part Two, is that turbulent motions of the ocean move heat much more effectively than conduction. The value can’t be calculated from first principles because that would mean solving the problem of turbulence, which is one of the toughest problems in physics. Instead it has to be estimated from measurements.

There is an inherent problem with eddy diffusivity for vertical heat transfer that we will come back to shortly.

There is also a minor problem of notation that is “solved” here by changing the notation. Usually conductivity is written as “k”. However, most papers on eddy diffusivity write diffusivity as “k”, sometimes “K”, sometimes “κ” (Greek ‘kappa’) – creating potential confusion so I revert back to “α”. And to make it clear that it is the convective value rather than the conductive value, I use αeddy. And for the equivalent parameter to conductivity, keddy.

keddy = αeddycpρ

because cp= 4200 J/K.kg and ρ ≈ 1000 kg/m³:

keddy =4.2 x 106 αeddy – it’s useful to be able to see what the diffusivity means in terms of an equivalent “conductivity” type parameter

Measurements of Eddy Diffusivity

Oeschger et al (1975):

α is an apparent global eddy diffusion coefficient which helps to reproduce an average transport phenomenon consisting of a series of distinct and overlapping mechanisms.

Oeschger and his co-workers studied the problem via the diffusion into the ocean of 14C from nuclear weapons testing.

The range they calculated for αeddy = 1 x 10-4 – 1.8 x 10-4 m²/s.

This equates to keddy = 420 – 760 W/m.K, and by comparison, the conductivity of still water, k = 0.6 W/m.K – making convection around 1,000 times more effective at moving heat vertically through the ocean.

Broecker et al (1980) took a similar approach to estimating this value and commented:

We do not mean to imply that the process of vertical eddy mixing actually occurs within the body of the main oceanic thermocline. Indeed, the values we require are an order of magnitude greater than those permitted by conventional oceanographic wisdom (see Garrett, 1979, for summary).

The vertical eddy coefficients used here should rather be thought of as parameters that take into account all the processes that transfer tracers across density horizons. In addition to vertical mixing by eddies, these include mixing induced by sediment friction at the ocean margins and mixing along the surface in the regions where density horizons outcrop.

Their calculation, like Oeschger’s, used a simple model with the observed values plugged in to estimate the parameter:

Anyone familiar with the water mass structure and ventilation dynamics of the ocean will quickly realize that the box-diffusion model is by no means a realistic representation. No simple modification to the model will substantially improve the situation.

To do so we must take a giant step in complexity to a new generation of models that attempt to account for the actual geometry of ventilation of the sea. We are as yet not in a position to do this in a serious way. At least a decade will pass before a realistic ocean model can be developed.

The values they calculated for eddy diffusivity were broken up into different regions:

- αeddy(equatorial) = 3.5 x 10-5 m²/s

- αeddy(temperate) = 2.0 x 10-4 m²/s

- αeddy(polar) = 3.0 x 10-4 m²/s

We will use these values from Broecker to see what happens to the measurement problems of climate sensitivity when used in my simple model.

These two papers were cited by Hansen et al in their 1985 paper with the values for vertical eddy diffusivity used to develop the value of the “effective mixed depth” of the ocean.

In reviewing these papers and searching for more recent work in the field, I tapped into a rich vein of research that will be the subject of another day.

First, Ledwell et al (1998) who measured eddy diffusivity via SF6 that they injected into the ocean:

The diapycnal eddy diffusivity K estimated for the first 6 months was 0.12 ± 0.02 x10-4 m²/s, while for the subsequent 24 months it was 0.17 ± 0.02 x10-4 m²/s.

[Note: units changed from cm²/s into m²/s for consistency]

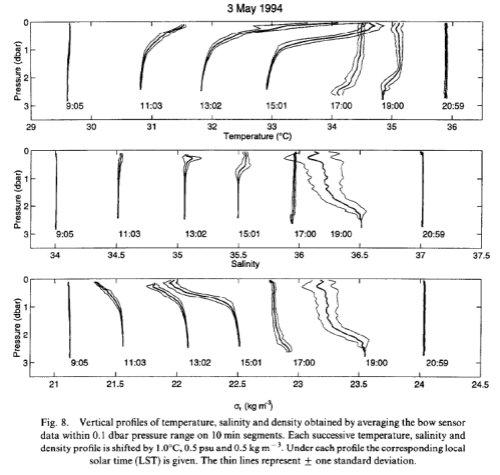

It is worth reading their comment on this aspect of ocean dynamics. (Note that isopycnal = contact density surfaces and diapycnal = across isopycnal):

The circulation of the ocean is severely constrained by density stratification. A water parcel cannot move from one surface of constant potential density to another without changing its salinity or its potential temperature. There are virtually no sources of heat outside the sunlit zone and away from the bottom where heat diffuses from the lithosphere, except for the interesting hydrothermal vents in special regions. The sources of salinity changes are similarly confined to the boundaries of the ocean. If water in the interior is to change potential density at all, it must be by mixing across density surfaces (diapycnal mixing) or by stirring and mixing of water of different potential temperature and salinity along isopycnal surfaces (isopycnal mixing).

Most inferences of dispersion parameters have been made from observations of the large-scale fields or from measurements of dissipation rates at very small scales. Unambiguously direct measurements of the mixing have been rare. Because of the stratification of the ocean, isopycnal mixing involves very different processes than diapycnal mixing, extending to much greater length scales. A direct approach to the study of both isopycnal and diapycnal mixing is to release a tracer and measure its subsequent dispersal. Such an experiment, lasting 30 months and involving more than 105 km² of ocean, is the subject of this paper.

From Jayne (2009):

For example, the Community Climate Simulation Model (CCSM) ocean component model uses a form similar to Eq. (1), but with an upper-ocean value of 0.1 x 10-4 m²/s and a deep-ocean value of 1.0 x 10-4 m²/s, with the transition depth at 1000 m.

However, there is no observational evidence to suggest that the mixing in the ocean is horizontally uniform, and indeed there is significant evidence that it is heterogeneous with spatial variations of several orders of magnitude in its intensity (Polzin et al. 1997; Ganachaud 2003).

More on eddy diffusivity measurements in another article – the parameter has a significant impact on modeling of the ocean in GCMs and there is a lot of current research into this subject.

Eddy Diffusivity and Buoyancy Gradient

Sarmiento et al (1976) measured isotopes near the ocean floor:

Two naturally occurring isotopes can be applied to the determination of the rate of vertical turbulent mixing in the deep sea: 222Rn (half-life 3.824 days) and 228Ra (half-life 5.75 years). In this paper we discuss the results from fourteen 222Rn and two 228Ra profiles obtained as part of the GEOSECS program.

From these results we conclude that the most important factor influencing the vertical eddy diffusivity is the buoyancy gradient [(g/p)(∂ρpot/∂z)]. The vertical diffusivity shows an inverse proportionality to the buoyancy gradient.

Their paper is very much about the measurements and calculations of the deeper ocean, but is relevant for anywhere in the ocean, and helps explain why the different values for different regions were obtained by Broecker that we saw earlier. (Prof. Wallace S. Broecker was a co-author on this paper as well, and has authored/co-authored 100’s of papers on the ocean).

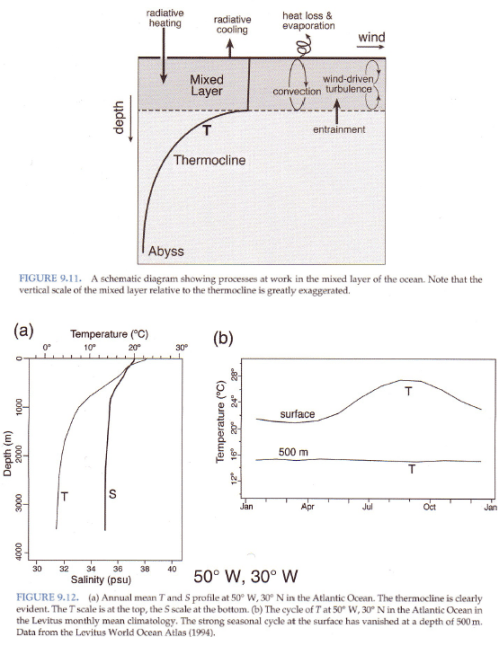

What is the buoyancy gradient and why does it matter?

Cold fluids sink and hot fluids rise. This is because cold substances contract and so are more dense. So in general, in the ocean, the colder water is below and the warmer water above. Probably everyone knows this.

The buoyancy gradient is a measure of how strong this effect is. The change in density with depth determines how resistant the ocean is to being overturned. If the ocean was totally stable no heat would ever penetrate below the mixed layer. But it does. And if the ocean was totally stable then the measurements of 14C from nuclear testing would be zero below the mixed layer.

But it is not surprising that the more stable the ocean is due to the buoyancy gradient the less heat diffuses down by turbulent motion.

And this is why the estimates by Broecker shown earlier have a much lower value of diffusivity for the tropics than for the poles. In general the poles are where deep convection takes place – lots of cold water sinks, mixing the ocean – and the tropics are where much weaker upwelling takes place – because the ocean surface is strongly heated. This is part of the large scale motion of the ocean, known as the thermohaline circulation. More on this another day.

Now water is largely incompressible which means that the density gradient is only determined by temperature and salinity. This creates the problem that eddy diffusivity is a value which is not only parameterized, but also dependent on the vertical temperature difference in the ocean.

Heat flow also depends on temperature difference, but with the opposite relationship. This is not something to untangle today. Today we will just see what happens to our simple model when we use the best estimates of vertical eddy diffusivity.

Modeling, Non-Linearity and Climate Sensitivity Measurement Problems

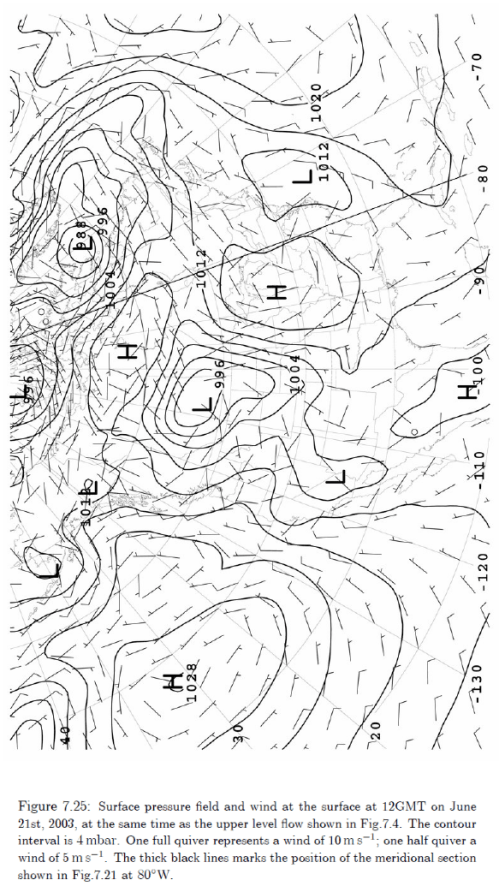

Murphy & Forster agreed in part with Spencer & Braswell about the variation in radiative noise from CERES measurements. I quote at length, because the Murphy & Forster paper is not freely available:

For the parameter N, SB08 use a random daily shortwave flux scaled so that the standard deviation of monthly averages of outgoing radiation (N – λT) is 1.3 W/m².

They base this on the standard deviation of CERES shortwave data between March 2000 and December 2005 for the oceans between 20 °Nand 20 °S.

We have analyzed the same dataset and find that, after the seasonal cycle and slow changes in forcing are removed, the standard deviation of monthly means of the shortwave radiation is 1.24 W/m², close to the 1.3 W/m² specified by SB08. However, longwave (infrared) radiation changes the energy budget just as effectively from the earth as shortwave radiation (reflected sunlight). Cloud systems that might induce random fluctuations in reflected sunlight also change outgoing longwave radiation. In addition, the feedback parameter λ is due to both longwave and shortwave radiation.

Modeled total outgoing radiation should therefore be compared with the observed sum of longwave and shortwave outgoing radiation, not just the shortwave component. The standard deviation of the sum of longwave and shortwave radiation in the same CERES dataset is 0.94 W/m². Even this is an upper limit, since imperfect spatial sampling and instrument noise contribute to the standard deviation.

[Note I change their α (climate feedback) to λ for consistency with previous articles].

And they continue:

We therefore use 0.94 W/m² as an upper limit to the standard deviation of outgoing radiation over the tropical oceans. For comparison, the standard deviation of the global CERES outgoing radiation is about 0.55 W/m².

All of these points seem valid (however, I am still in the process of examining CERES data, and can’t comment on their actual values of standard deviation. Apart from the minor challenge of extracting the data from the netCDF format there is a lot to examine. A lot of data and a lot of issues surrounding data quality).

However, it raised an interesting idea about non-linearity. Readers who remember on Part One will know that as radiative noise increases and ocean MLD decreases the measurement problem gets worse. And as the radiative noise decreases and ocean MLD increases the measurement problem goes away.

If we average global radiative noise and global MLD, plug these values into a zero-dimensional model and get minimal measurement problem what does this mean?

Due to non-linearity, it tells us nothing.

Averaging the inputs, applying them to a global model (i.e., a zero-dimensional model) and calculating λest (from the regression) gets very different results from applying the inputs separately to each region, averaging the results and calculating λest

I tested this with a simple model – created two regions, one 10% of the surface area, the other 90%. In the larger region the MLD was 200m and the radiative noise was zero; and in the smaller region the MLD was 20m and the (standard deviation of) radiative noise was varied from 0 – 2. The temperature and radiative flux were converted into an area weighted time series and the regression produced large deviations from the real value of λ.

A similar run on a global model with an MLD of 180m and radiative noise of 0-0.2 shows an accurate assessment of λ.

This is to be expected of course.

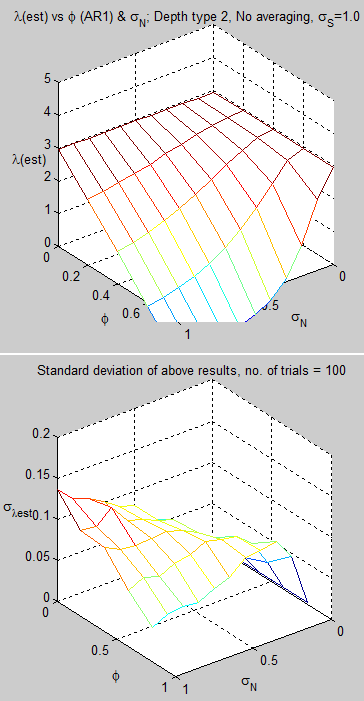

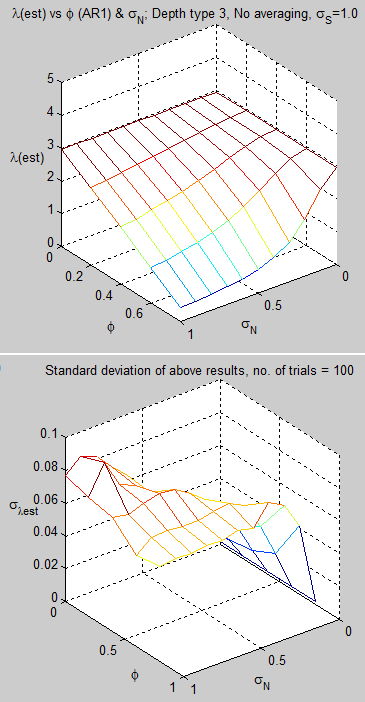

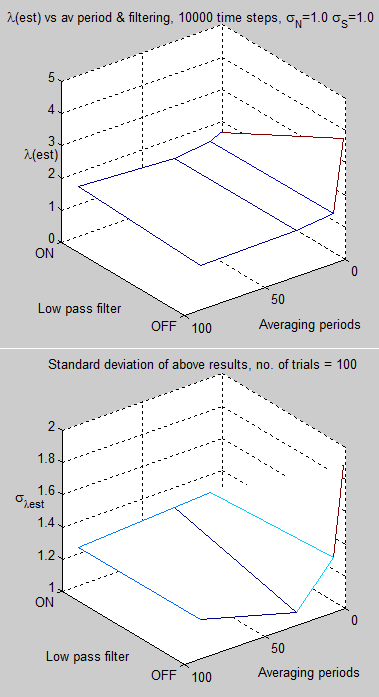

So with this in mind I tested the new 1D model with different values of ocean depth eddy diffusivity, radiative noise, and an AR(1) model for the radiative noise. I used values for the tropical region as this is clearly the area most likely to upset the measurement – shallow MLD, higher radiative noise and weaker eddy diffusivity.

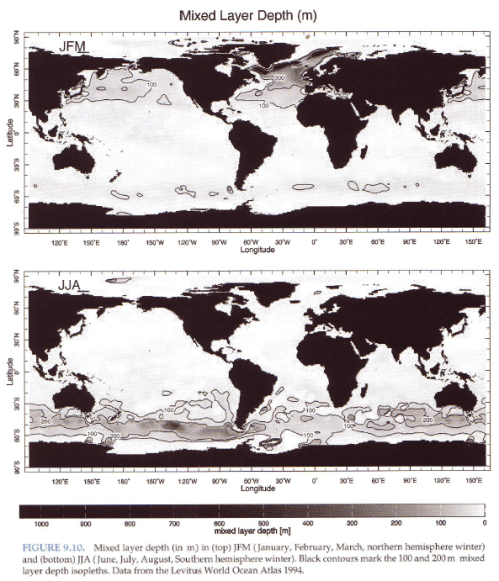

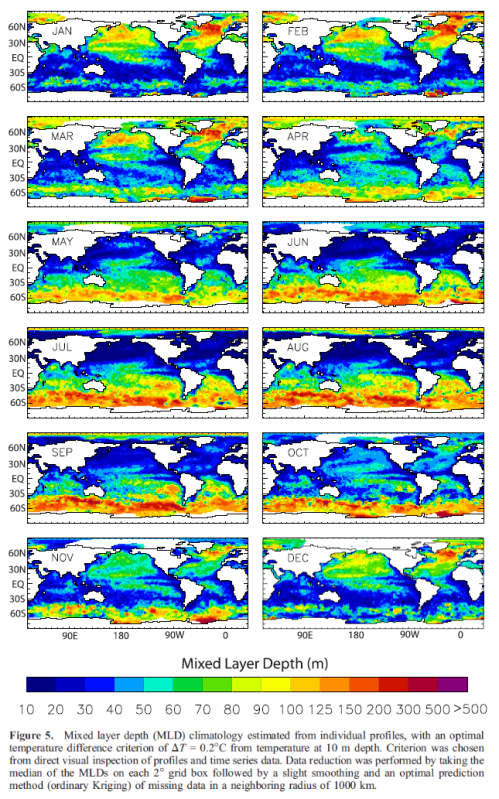

As best as I could determine from de Boyer Montegut’s paper, the average MLD for the 20°N – 20°S region is approximately 30m.

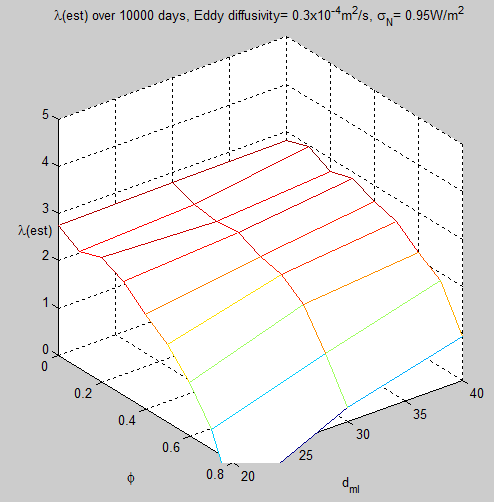

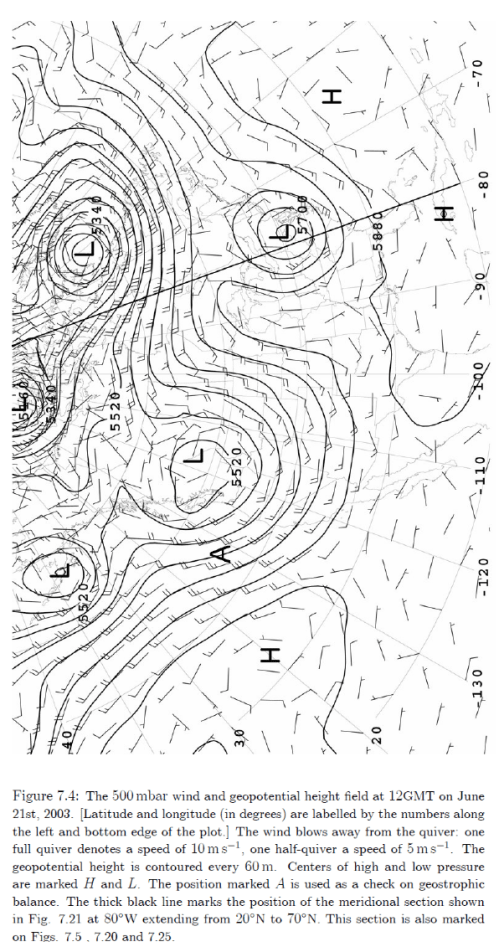

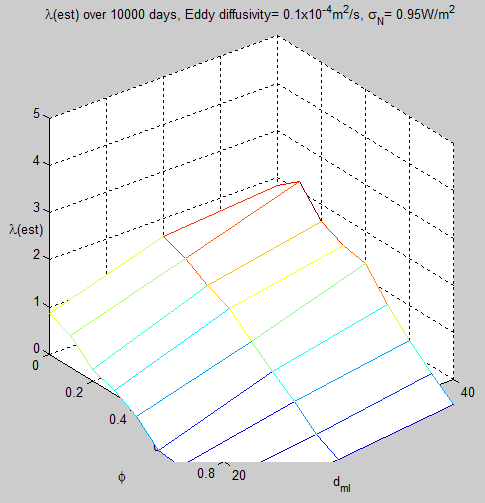

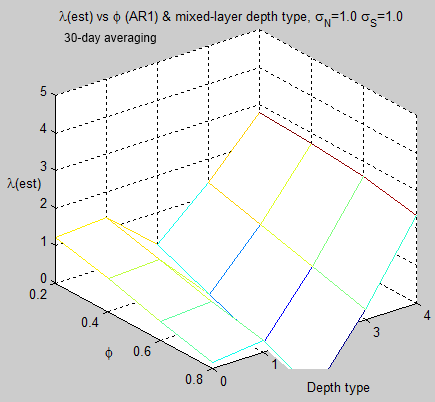

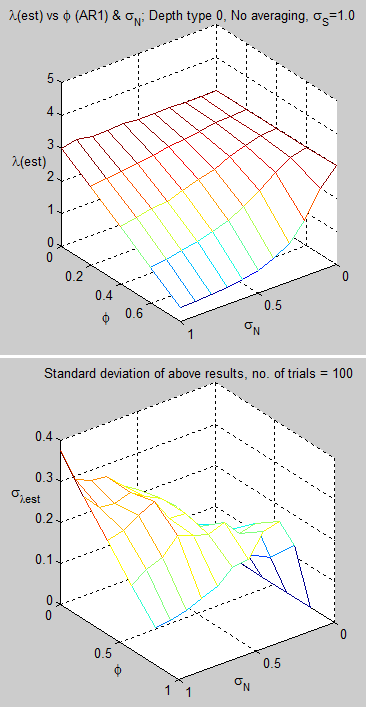

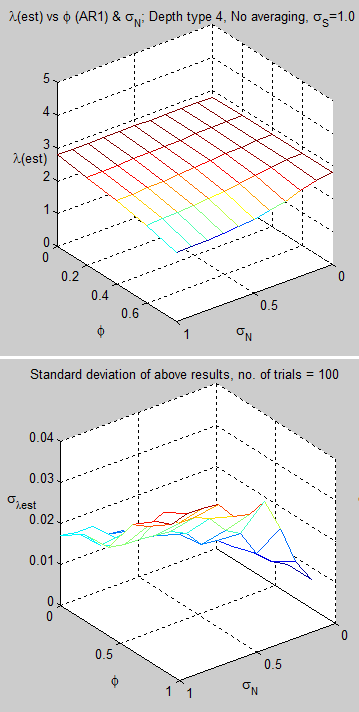

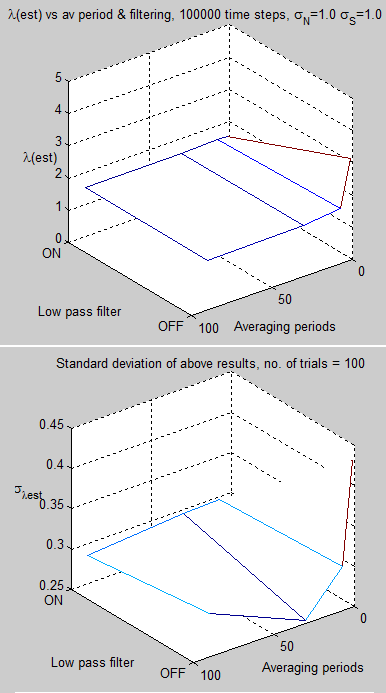

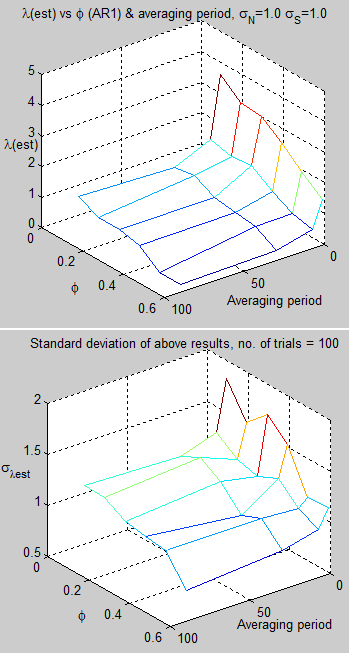

Here are the results using Oeschger’s value of eddy diffusivity for the tropics and the tropical value of radiative noise from MF2010 – varying ocean depth around 30m and the value of the AR(1) model for radiative noise:

Figure 1

For reference, as it’s hard to read off the graph, the value at 30m and φ=0.5 is λest = 2.3.

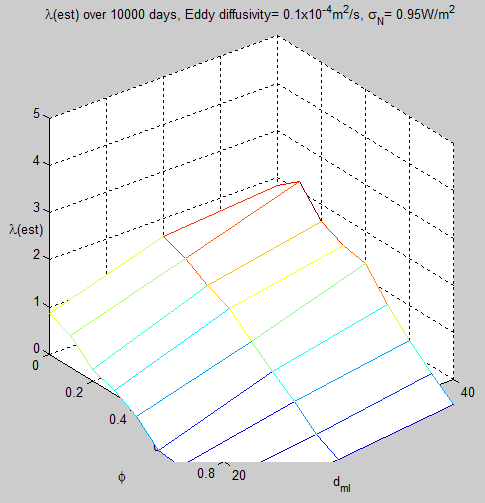

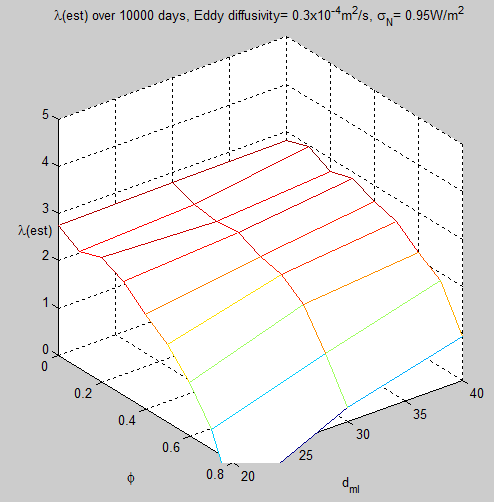

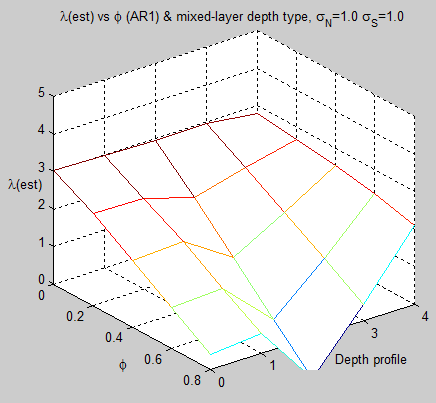

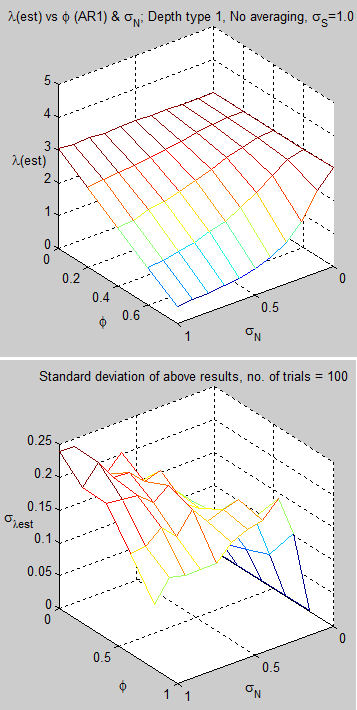

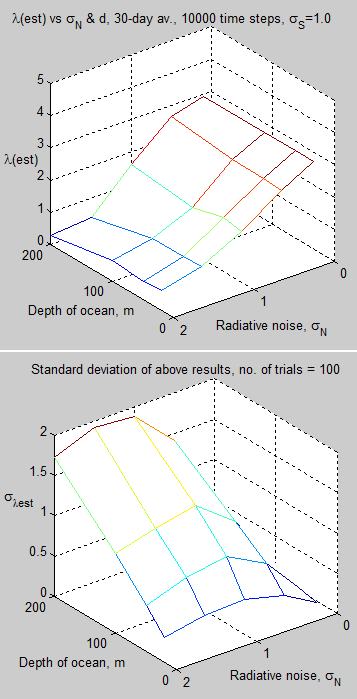

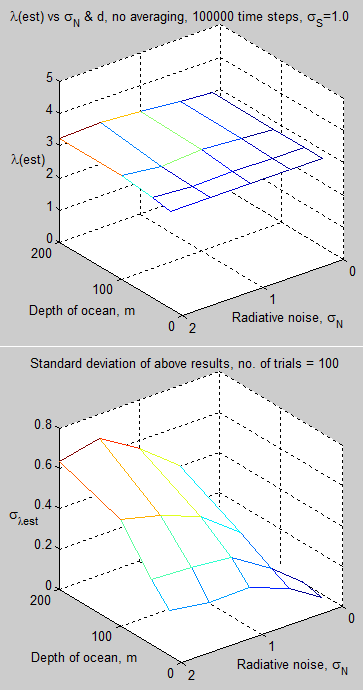

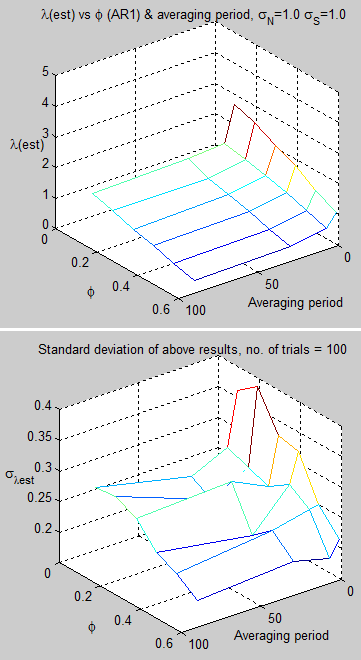

Using the current CCSM value of eddy diffusivity for the upper ocean:

Figure 2

For reference, the value at 30m and φ=0.5 is λest = 0.2. (Compared with the real value of 3.0)

Note that these values are only for one region, not for the whole globe.

Another important point is that I have used the radiative noise value as the standard deviation of daily radiative noise. I have started to dig into CERES data to see whether such a value can be calculated, and also what typical value of autoregressive parameter should be used (and what kind of ARMA model), but this might take some time.

Yet smaller values of eddy diffusivity are possible for smaller regions, according to Jochum (2009). This would likely cause the problems of estimating climate sensitivity to become worse.

Simple Models

Murphy & Forster comment:

Although highly simplified, a single box model of the earth has some pedagogic value. One must remember that the heat capacity c and feedback parameter λ are not really constants, since heat penetrates more deeply into the ocean on long time scales and there are fast and slow climate feedbacks (Knutti et al. 2008).

It is tempting to add a few more boxes to account for land, ocean, different latitudes, and so forth. Adding more boxes to an energy balancemodel can be problematic because one must ensure that the boxes are connected in a physically consistent way. A good option is to instead consider a global climate model that has many boxes connected in a physically consistent manner.

The point being that no one believes a slab model of the ocean to be a model that gives really useful results. Spencer & Braswell likewise don’t believe that the slab model is in any way an accurate model of the climate.

They used such a model just to demonstrate a possible problem. Murphy & Forster’s criticism doesn’t seem to have solved the problem of “can we measure climate sensitivity?”

Or at least, it appears easy to show that slightly different enhancements of the simple model demonstrate continued problems in measuring climate sensitivity – due to the impact of radiative noise in the climate system.

Conclusion

I have produced a simple model and apparently demonstrated continued climate sensitivity measurement problems. This is in contrast to Murphy & Forster who took a different approach and found that the problem went away. However, my model has a more realistic approach to moving heat from the mixed layer into the ocean depths than theirs.

My model does have the drawback that the massive army of Science of Doom model testers and quality control champions are all away on their Xmas break. So the model might be incorrectly coded.

It’s also likely that someone else can come along and take a slightly enhanced version of this model and make the problem vanish.

I have used values for MLD and eddy diffusivity that seem to represent real-world values but I have no idea as to the correct values for standard deviation and auto-correlation of daily radiative noise (or appropriate ARMA model). These values have a big impact on the climate sensitivity measurement problem for reasons explained in Part One.

A useful approach to determining the effect of radiative noise on climate sensitivity measurement might be to use a coupled atmosphere-ocean GCM with a known climate sensitivity and an innovative way of removing radiative noise. These kind of experiments are done all the time to isolate one effect or one parameter.

Perhaps someone has already done this specific test?

I see other potential problems in measuring climate sensitivity. Here is one obvious problem – as the temperature of the mixed layer increases with continued increases in radiative forcing the buoyancy gradient increases and the eddy diffusivity reduces. We can calculate radiative forcing due to “greenhouse” gases quite accurately and therefore remove it from the regression analysis (see Spencer & Braswell 2008 for more on this). But we can’t calculate the change in eddy diffusivity and heat loss to the deeper ocean. This adds another “correlated” term that seems impossible to disentangle from the climate sensitivity calculation.

An alternative way of looking at this is that climate sensitivity might not be a constant – as already noted in Part One.

Articles in this Series

Measuring Climate Sensitivity – Part One

Measuring Climate Sensitivity – Part Two – Mixed Layer Depths

References

Potential Biases in Feedback Diagnosis from Observational Data: A Simple Model Demonstration, Spencer & Braswell, Journal of Climate (2008) – FREE

On the accuracy of deriving climate feedback parameters from correlations between surface temperature and outgoing radiation, Murphy & Forster, Journal of Climate (2010)

A box diffusion model to study the carbon dioxide exchange in nature, Oeschger et al, Tellus (1975)

Modeling the carbon system, Broecker et al, Radiocarbon (1980) – FREE

Climate response times: dependence on climate sensitivity and ocean mixing, Hansen et al, Science (1985)

The study of mixing in the ocean: A brief history, MC Gregg, Oceanography (1991) – FREE

Spatial Variability of Turbulent Mixing in the Abyssal Ocean, Polzin et al, Science (1997) – FREE

The Impact of Abyssal Mixing Parameterizations in an Ocean General Circulation Model, Steven R. Jayne, Journal of Physical Oceanography (2009)

The relationship between vertical eddy diffusion and buoyancy gradient in the deep sea, Sarmiento et al, Earth & Planetary Science Letters (1976)

Mixing of a tracer in the pycnocline, Ledwell et al, JGR (1998)

Impact of latitudinal variations in vertical diffusivity on climate simulations, Jochum, JGR (2009) – FREE

Mixed layer depth over the global ocean: An examination of profile data and a profile-based climatology, de Boyer Montegut et al, JGR (2004)

Notes

Note 1: The 1D version is really:

∂T / ∂t = ∂/∂z (α.∂T/∂z)

due to the fact that α can be a function of z (and definitely is in the case of the ocean).

Although this looks tricky – and it is tricky to find analytical solutions – solving the 1D version numerically is very straightforward and anyone can do it.

In plain English is looks something like:

– Heat flow into cell X = temperature difference between cell X and cell X-1

– Heat flow out of cell X = temperature difference between cell X and cell X+1

– Change in temperature = (Heat flow into cell X – Heat flow out of cell X) x time / heat capacity

Note 2: I am in the process of examining CERES data. Apart from the challenge of extracting the data from the netCDF format there is a lot to examine. A lot of data and a lot of issues surrounding data quality.

“Blah blah blah” vs Equations

January 30, 2012 by scienceofdoom

It is not surprising that the people most confused about basic physics are the ones who can’t write down an equation for their idea.

The same people are the most passionate defenders of their beliefs and I have no doubts about their sincerity.

I’ll meander into what it is I want to explain..

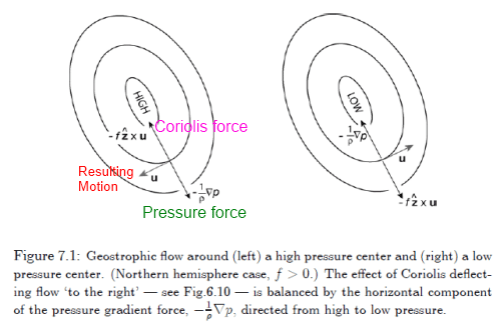

I found an amazing resource recently – iTunes U short for iTunes University. Now I confess that I have been a little confused about angular momentum. I always knew what it was, but in the small discussion that followed The Coriolis Effect and Geostrophic Motion I found myself wondering whether conservation of angular momentum was something independent of, or a consequence of, linear momentum or some aspect of Newton’s laws of motion.

It seemed as if conservation of angular momentum was an orphan of Newton’s three laws of motion. How could that be? Perhaps this conservation is just another expression of these laws in a way that I hadn’t appreciated? (Knowledgeable readers please explain).

Just around this time I found iTunes U and searched for “mechanics” and found the amazing series of lectures from MIT by Prof. Walter Lewin. A series of videos. I recommend them to anyone interested in learning some basics about forces, motion and energy. Lewin has a gift, along with an engaging style. It’s nice to see chalk boards and overhead projectors because they are probably no more in use (? young people please advise).

These lectures are not just for iPhone and iTunes people – here is the weblink.

The gift of teaching science is not in accuracy – that’s a given – the gift is in showing the principle via experiment and matching it with a theoretical derivation, and “why this should be so” and thereby producing a conceptual idea in the student.

I haven’t got to Lecture 20: Angular Momentum yet, I’m at about lecture 11. It’s basic stuff but so easy to forget (yes, quite a lot of it has been forgotten). Especially easy to forget how different principles link together and which principle is used to derive the next principle.

For example, in deriving the work done on an object, Lewin integrates force over the distance traveled and comes up with the equation for kinetic energy.

While investigating the oscillation of a mass on a spring, the equation for its harmonic motion is derived.

Every principle has an equation that can be written down.

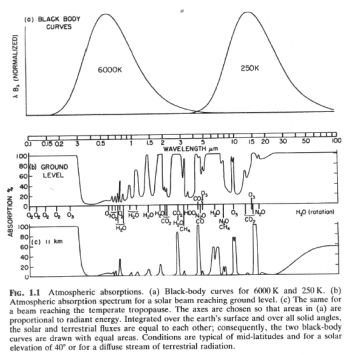

Over the last few days, as at many times over the past two years, people have arrived on this blog to explain how radiation from the atmosphere can’t affect the surface temperature because of blah blah blah. Where blah blah blah sounds like it might be some kind of physics but is never accompanied by an equation.

Here’s the equation I find in textbooks.

Energy absorbed from the atmosphere by the surface, Ea:

Ea = αRL↓ ….[eqn 1]

where α = absorptivity of the surface at these wavelengths, RL↓ = downward radiation from the atmosphere

And this energy absorbed, once absorbed, is indistinguishable from the energy absorbed from the sun. 1 W/m² absorbed from the atmosphere is identical to 1 W/m² absorbed from the sun.

That’s my equation. I have provided six textbooks to explain this idea in a slightly different way in Amazing Things we Find in Textbooks – The Real Second Law of Thermodynamics.

It’s also produced by Kramm & Dlugi, who think the greenhouse effect is some unproven idea:

Now the equation shown is a pretty simple equation. The equation reproduced in the graphic above from Kramm & Dlugi looks a little more daunting but is simply adding up a number of fluxes at the surface.

Here’s what it says:

Solar radiation absorbed + longwave radiation absorbed – thermal radiation emitted – latent heat emitted – sensible heat emitted + geothermal energy supplied = 0

Or another way of thinking about it is energy in = energy out (written as “energy in – energy out = 0“)

Now one thing is not amazing to me – of the tens (hundreds?) of concerned citizens commenting on the many articles on this subject who have tried to point out my “basic mistake” and tell me that the atmosphere can’t blah blah blah, not a single one has produced an equation.

The equation might look something like this:

Ea = f(α,Tatm-Tsur).RL↓ ….[eqn 2]

where Tatm = temperature of the atmosphere, Tsur = temperature of the surface

With the function f being defined like this:

f(α,Tatm-Tsur) = α, when Tatm ≥ Tsur and

f(α,Tatm-Tsur) = 0, when Tatm < Tsur

In English, it says something like energy from the atmosphere absorbed by the surface = 0 when the temperature of the atmosphere is less than the temperature of the surface.

I’m filling in the blanks here. No one has written down such ridiculous unphysical nonsense because it would look like ridiculous unphysical nonsense. Or perhaps I’m being unkind. Another possibility is that no one has written down such ridiculous unphysical nonsense because the proponents have no idea what an equation is, or how one can be constructed.

My Prediction

No one will produce an equation which shows how no atmospheric energy can be absorbed by the surface. Or how atmospheric energy absorbed cannot affect internal energy.

This is because my next questions will be:

My Challenge

Here’s my challenge to the many people concerned about the “dangerous nonsense” of the atmospheric radiation affecting surface temperature –

Supply an equation.

If you can’t, it is because you don’t understand the subject.

It won’t stop you talking, but everyone who is wondering and reads this article will be able to join the dots together.

The Usual Caveat

If there were only two bodies – the warmer earth and the colder atmosphere (no sun available) – then of course the earth’s temperature would decrease towards that of the atmosphere and the atmosphere’s temperature would increase towards that of the earth until both were at the same temperature – somewhere between the two starting temperatures.

However, the sun does actually exist and the question is simply whether the presence of the (colder) atmosphere affects the surface temperature compared with if no atmosphere existed. It is The Three Body Problem.

My Second Prediction

The people not supplying the equation, the passionate believers in blah blah blah, will not explain why an equation is not necessary or not available. Instead, continue to blah blah blah.

Posted in Basic Science, Commentary | 455 Comments »