Recap

Part One of the series started with this statement:

If there’s one area that often seems to catch the imagination of many who call themselves “climate skeptics”, it’s the idea that CO2 at its low levels of concentration in the atmosphere can’t possibly cause the changes in temperature that have already occurred – and that are projected to occur in the future. Instead, the sun, that big bright hot thing in the sky (unless you live in England), is identified as the most likely cause of temperature changes.

Part One looked mainly at the radiation balance – what the sun provides (lots of energy at shortwave) and what the earth radiates out (longwave). Then it showed how “greenhouses gases” – water vapor, CO2 and methane (plus some others) – absorb longwave radiation and re-emit radiation both up out of the atmosphere and back down to the earth’s surface. And without this absorption of longwave radiation the earth would be 35°C cooler at its surface. The post concluded with:

CO2 and water vapor are very significant in the earth’s climate, otherwise it would be a very cold place.

What else can we conclude? Nothing really, this is just the starting point. It’s not a sophisticated model of the earth’s climate, it’s a “zero dimensional model”.. the model takes a very basic viewpoint and tries to establish the effect of the sun and the atmosphere on surface temperature. It doesn’t look at feedback and it’s very simplistic.

Two images to remember..

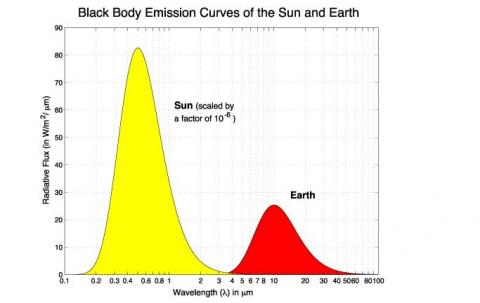

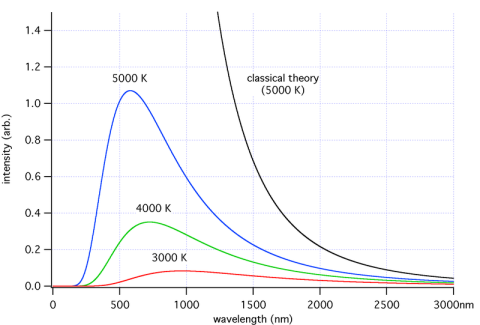

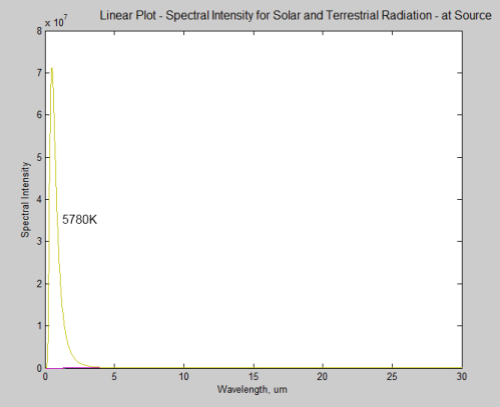

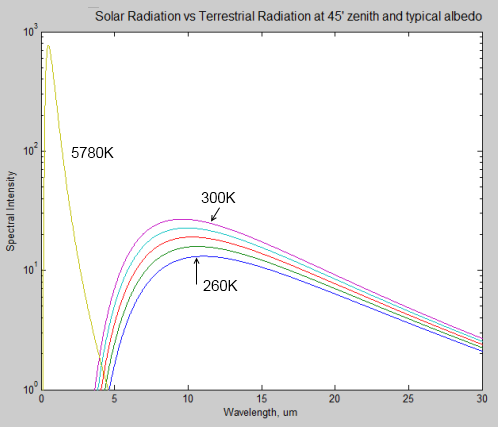

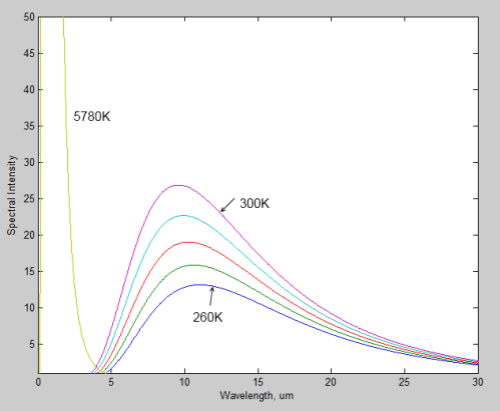

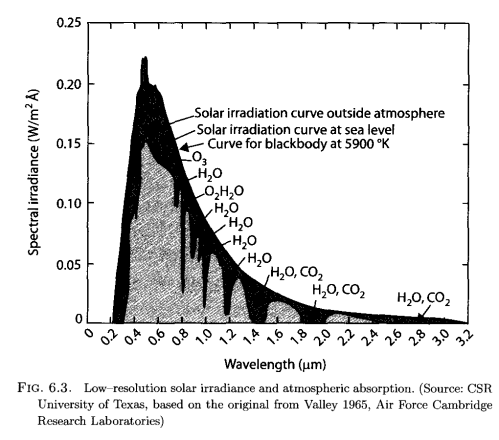

First, the sun’s radiated energy is mostly under 4μm in wavelength (shortwave), while the earth’s radiated energy is over 4μm (longwave), meaning that we can differentiate the two very easily:

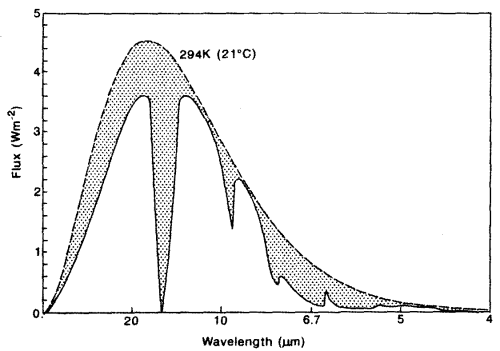

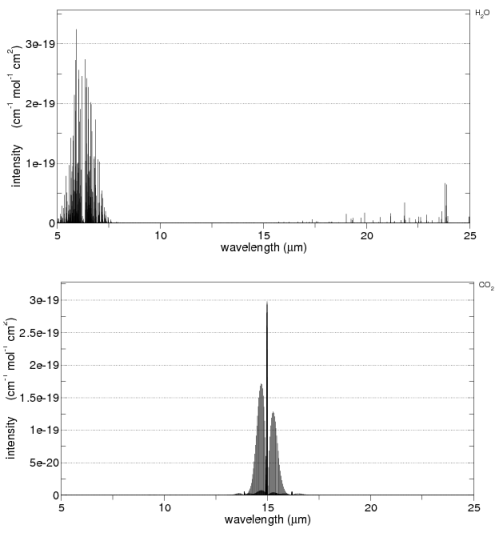

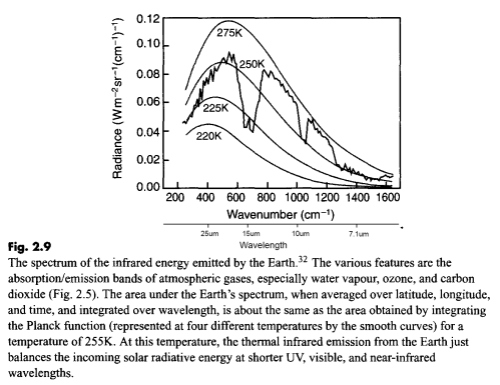

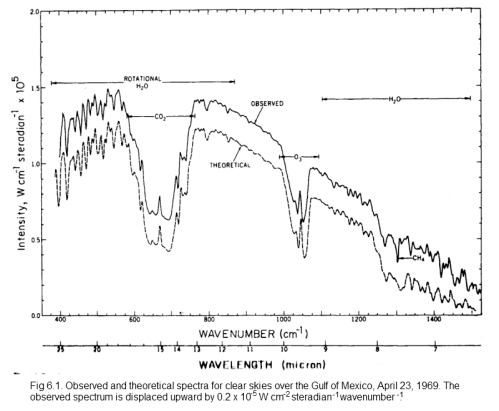

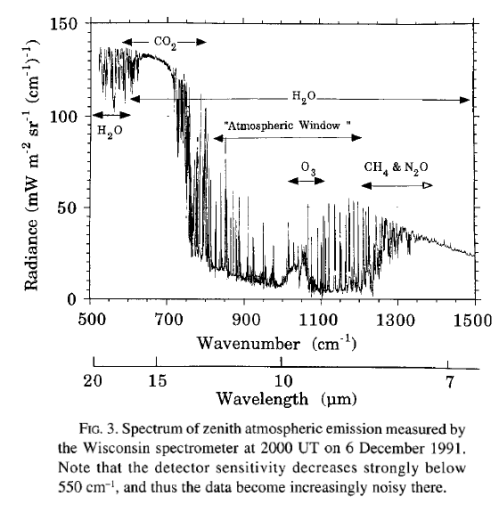

Second, the aborption that we can easily measure in the earth’s longwave radiation from different molecules:

Recap over.. This post was going to introduce the basic 1-d model of radiative transfer, but enough people asked questions about the absorption properties of gases that I thought it was was worth covering in more detail.. The 1-d model will have to wait until Part Three.

Why don’t the Atmospheric Gases Absorb Energy according to their Relative Volume?

Just because CO2 only consists of 0.04% of gases doesn’t mean it only contributes 0.04% of atmospheric absorption and re-emission of long wave radiation. Why is that?

Oxygen, O2, constitutes 21% of the atmophere and nitrogen, N2, constitutes 78%. Why aren’t they important “greenhouse” gases? Why are water vapor, CO2 and methane (CH4) the most important when they are present in such small amounts?

For reference, the three most important gases by volume are:

- Water vapor – 0.4% averaged throughout the atmosphere, but actual value in any one place and time varies (See note 1 at end of article)

- CO2 – 0.04% (380ppmv), well mixed (note: ppmv is parts per million by volume)

- CH4 – 0.00018% (1.8ppmv), well mixed

Now there are three factors in determining the effect of longwave absorption:

- The amount of the gas by volume

- How much longwave energy is radiated from the earth at wavelengths that the gas absorbs

- The ability of the gas to absorb energy at a given wavelength

The first one is the simplest to understand. In fact, it’s knowing only this factor that causes so much confusion.

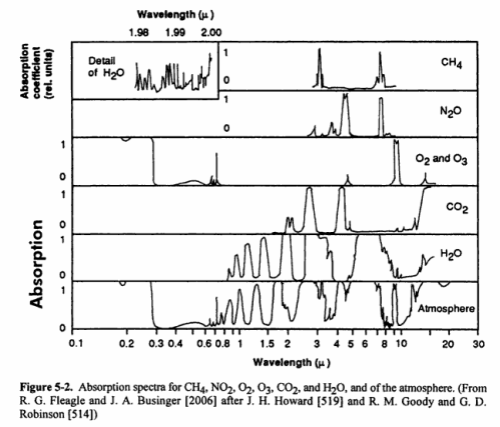

The second point is not immediately obvious, but should become clearer by reviewing the earth’s radiation spectrum:

Different amounts of energy are radiated at different wavelengths. For example, the amount of energy emitted between 10-11μm is eight times the amount of energy between 4-5μm (for radiation from a surface temperature of 15 °C or 288K).

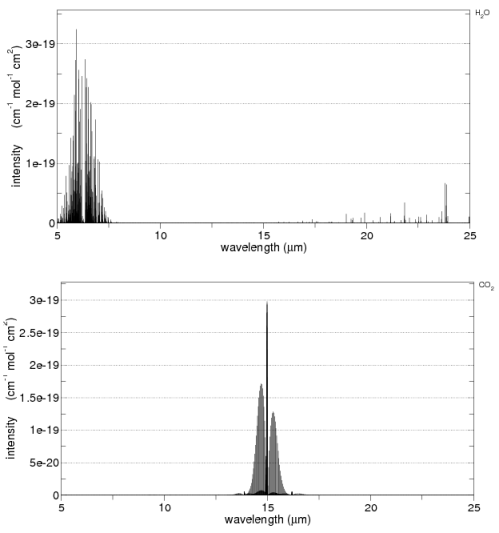

CO2 has a wide absorption band centered around 15μm, which is where the long-wave radiation from the earth is at almost its highest level. By contrast, one of water vapor’s absorption lines is at 6.27μm – where the radiation is a slightly lower level (about 25% less) and more importantly, the other water vapor absorption lines are where the radiation is 5-10x lower intensity.

However, there is around 10x as much water vapor than CO2 in the atmosphere, which is why it is the most important greenhouse gas.

And Third, Why are Some Gases More Effective at Absorbing Longwave Energy?

Why aren’t O2 and N2 absorbers of longwave radiation?

Molecules with two identical atoms don’t change their symmetry when any rotation or vibration takes place. As a result they can’t move into different energy states.

But triatomic molecules like CO2, H2O and CH4 can bend as they vibrate. They can move into different energy states by changing their shape. Consequently they can absorb the energy from an incoming photon if its energy matches the new state.

And some molecules have many more energy states they can move into. This changes their absorption profile because their spectral breadth is effectively wider.

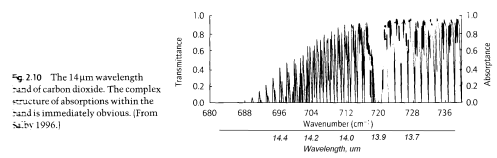

Here’s a graphic of one part of the actual CO2 absorption lines. Apologies for the poor quality scan..

(Note that the x-axis is “Wavenumber, cm-1”. This is a convention for spectral people. Wavenumber is the number of wavelengths present in 1cm. I added the actual wavelength underneath.)

This shows the complexity of the subject once we look at the real detail. In practice, these individual discrete absorption lines “broaden” due to pressure broadening (collisions with other molecules) and Doppler broadening (as a result of the absorbing molecule moving in the same or opposite direction to the photon of light).

However, the important point to remember is that different molecules absorb at different frequencies and across different ranges of frequencies.

This third factor is the most important in determining the absorption properties of longwave radiation.

As an interesting comparison, molecule by molecule methane absorbs about 20x as much energy as CO2. But of course it is present in much smaller quantities.

Here are water vapor and CO2 across 5-25μm from the HITRANS database:

See Note 2 at the end of the article.

What about Oxygen?

A digression on oxygen.. It is important in the earth’s atmosphere because it absorbs UV, but when these high energy photons from the sun interact with O2 it breaks into O+O. Then a cycle takes place where O2 and O combine to form O3 (ozone), and later O3 breaks up again. By the time the sun’s energy has reached the lower part of the atmosphere (troposphere) all of the lower wavelength energy (most of the UV) has been filtered out.

O3 itself does absorb some longwave energy, at 9.6um, but because there is so little O3 in the troposphere it is not very significant.

What Happens when a Greenhouse Gas Absorbs Energy?

Once a gas molecule has absorbed radiation from the earth it has a lot more energy. But in the lower 100km of the atmosphere, the absorbed energy is transferred to kinetic energy by collisions between the absorbing molecules and others in the layer. Effectively, it heats up this layer of the atmosphere.

The layer itself will act as a blackbody and re-radiate infrared radiation. But it re-radiates in all directions, including back down to the earth’s surface. (If it only radiated up away from the earth there would be no “greenhouse” effect from this absorption).

Conclusion

We are still on the “zero dimensional model” – some call it the billiard ball model – of the radiative balance in the earth’s climate system.

A few different factors affect the absorption of the earth’s longwave radiation by various gases.

O2 barely absorbs any (see note 2 below), and neither does N2 (nitrogen). Among the other gases – the main greenhouse gases being water vapor, CO2 and methane – we see that each one has different properties – none of which can be determined by our intuition!

Different molecules can absorb energy in certain frequencies simply because of their ability to change shape and move to different energy states. The primary property that creates a strong “greenhouse” effect is to have a strong and wide absorption around a wavelength that the earth radiates. This is centered about 10μm (and isn’t symmetrical) so the further away from the peak energy the absorption occurs, the less relevant that absorption line becomes in the earth’s energy balance.

In the next part in the series, we will look at the 1-dimensional model and also what happens when absorption in a wavelength is saturated.

Note 1 – Water Vapor ppmv: After consulting numerous reference works, I couldn’t find one which gave the averaged water vapor throughout the atmosphere, or the troposphere. The actual source for the 0.4% was Wikipedia.

Because all the reference works danced around without actually giving a number I suspect it is “up in the air”. Here is one example:

Water vapor concentration is highly variable, ranging from over 20,000 ppmv (2%) in the lower tropospherical atmosphere to only a few ppmv in the stratosphere..

Atmospheric Science for Environmental Scientists (2009) Hewitt & Jackson

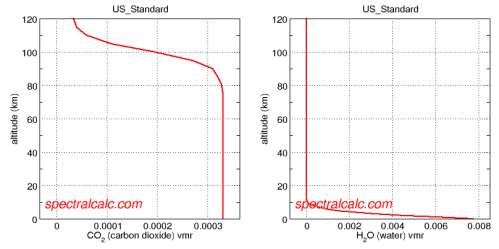

There is a great application, Spectral Calc for looking at atmospheric concentrations and absorption lines. Specifically http://spectralcalc.com/atmosphere_browser gives plots of atmospheric concentration and the data agrees with the Wikipedia number given in the body of this article:

Averaging over the whole atmosphere, the concentration of water vapor does seem to be around 10x the CO2 value.

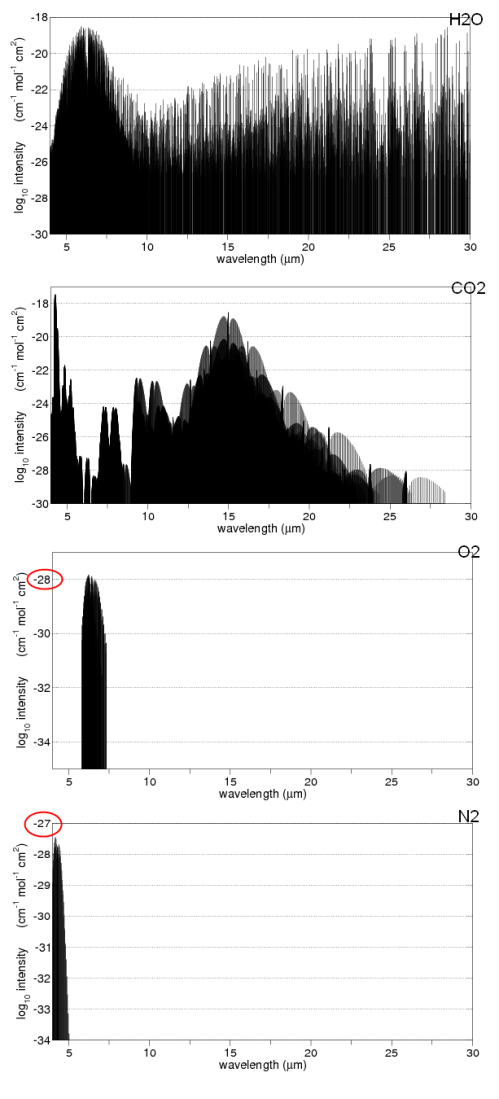

Note 2 – Optical Thickness: The spectral plots from the HITRANS database shown in the body of the article give the capture cross-section per mole (i.e. per “unit” of that gas, not per unit volume of the general atmosphere).

One commenter asked why another plot from a different website drawing on the same HITRANS database produced this:

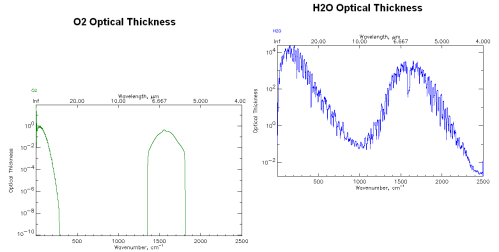

Optical Thickness of O2 and water vapor from http://www.atm.ox.ac.uk

Note that I’ve adjusted the plots so that similar values on the y-axes are aligned for both graphs. And note that the vertical axis is logarithmic.

His comment was that oxygen, O2, is only maybe 1000 times lower in absorption than water vapor (100 =1 vs 103 =1000) at 6.7μm and given that O2 is 20% of the atmosphere instead of 0.4%, O2 should be comparable to water vapor as a greenhouse gas.

But in fact, this graphical plot isn’t plotting the absorption by units of molecule – instead it is plotting Optical Thickness.

This is a handy variable which we will see more of in Part Three. Optical Thickness essentially takes the value of Intensity, which is per unit of molecules, and “integrates” that value up through the entire height of the atmosphere.

As a result it gives the picture of the complete influence of that gas at different frequencies without having to work out the relative proportions of the gas at different heights in the atmosphere.

So the example above compares the complete absorption (in a simplistic model) through the whole atmosphere, giving O2 about 3000x less effect than water vapor at 6.7μm.

Update – Part Three is now online

The IPCC and the Credibility of Climate Science

Posted in Climate Models, Commentary on January 26, 2010| 4 Comments »

First, what recent events (Jan 2010)?

The issues arising from the story in the UK Mail that the IPCC used “sexed-up” climate forecasts to put political pressure on world leaders:

Then there are a number of stories on a similar theme where the predictions of climate change catastrophe weren’t based on “peer-reviewed” literature but on reports from activist organizations, like the WWF. And the reports were written not by specialists in the field, but activists..

And these follow the “climategate” leak of November 2009 where emails from the CRU from prominent IPCC scientists like Phil Jones, Michael Mann, Keith Briffa and others show them in a poor light.

This blog is focused on the science but once you read stories like this you wonder how much of anything to believe.

If you are in one of those mindsets, this blog is probably the wrong place to come.

Be Skeptical

Being skeptical doesn’t mean not believing anything you hear. Being skeptical means asking for some evidence.

I see many individuals watching the recent events unfolding and saying:

Actually the two aren’t related. CO2 and the IPCC are not an indivisible unit!

It’s a challenge to keep a level head. To be a good skeptic means to realize that an organization can be flawed, corrupt even, but it doesn’t mean that all the people whose work it has drawn on have produced junk science.

When a government tries to convince its electorate that it has produced amazing economic results by stretching or inventing a few statistics, does this mean the statisticians working for that government are all corrupt, or even that the very science of statistics is clearly in error?

Most people wouldn’t come to that conclusion.

Politics and Science

But in climate science it’s that much harder because to understand the science itself takes some effort. The IPCC is a political body formed to get political momentum behind action to “prevent climate change”. Whereas climate science is mostly about physics and chemistry.

They are a long way apart.

For myself, I believe that the IPCC has been bringing the science of climate into disrepute for a long time, despite producing some excellent work. It has claimed too much certainty about what the science can predict. Tenuous findings that might possibly show that a warmer world will lead to more problems are pressed into service. Findings against are ignored.

This causes a problem for anyone trying to find out the truth.

It’s tempting to dismiss anything that is in an IPCC report because of these obvious flaws – and they have been obvious for a long time. But even that would be a mistake. Much of what the IPCC produces is of a very high quality. They have a bias, so don’t take it all on faith..

The Easy Answer

Find a group of people you like and just believe them.

The Road Less Travelled

My own suggestion, for what it’s worth, is to put time into trying to get a better understanding of climate science. Then it is that much easier to separate fact from fiction. One idea – if you live near a university, you can visit their library and probably find a decent entry-level book or two about climate science basics.

Another idea – for around $40 you can purchase Elementary Climate Physics by Prof. F.W. Taylor – from http://www.bookdepository.co.uk/ – free shipping around the world. Amazing. And I don’t get paid for this advert either, not until I work out how to get adverts down the side of the blog. It’s an excellent book with some maths, but skip the maths and you will still learn 10x more than reading any blog including mine.

And, of course, visit blogs which focus on the science and ask a few questions.

Be prepared to change your mind.

Read Full Post »