After posting Part Two on water vapor, some people were unhappy that questions from Part One were not addressed.

I have re-read through the many comments and questions and attempt to answer them here. I ignore the questions unrelated to the feedbacks of water vapor and clouds – like the many questions about the moon, answered in Lunar Madness and Physics Basics. I also ignore the personal attacks from a commenter that my article(s) was/were deceptive.

The Definition

The major point from the perspective of a few commenters (including critics of Part Two) was about the radiometric definition of the “greenhouse” effect.

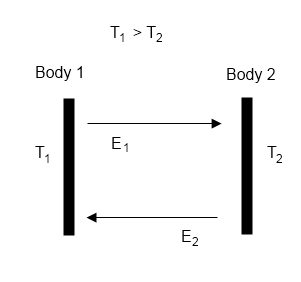

Ramanathan analyzed the following equation:

F = σT4 – G

where F is outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) at top of atmosphere (TOA), T is surface temperature, and G is the “greenhouse” effect.

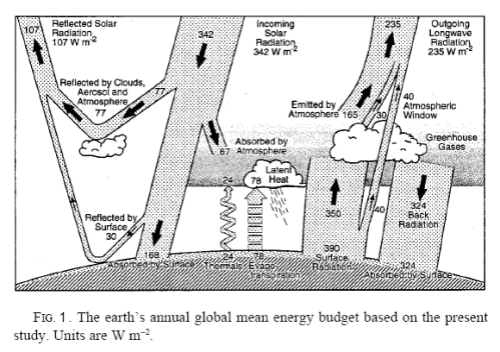

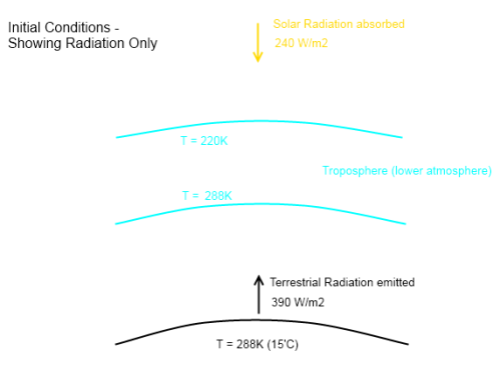

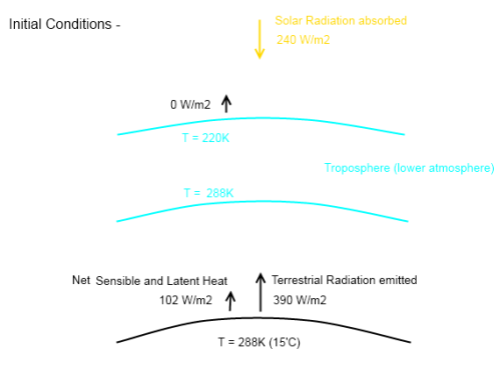

For newcomers, F averages around 240 W/m² (and higher in clear sky conditions).

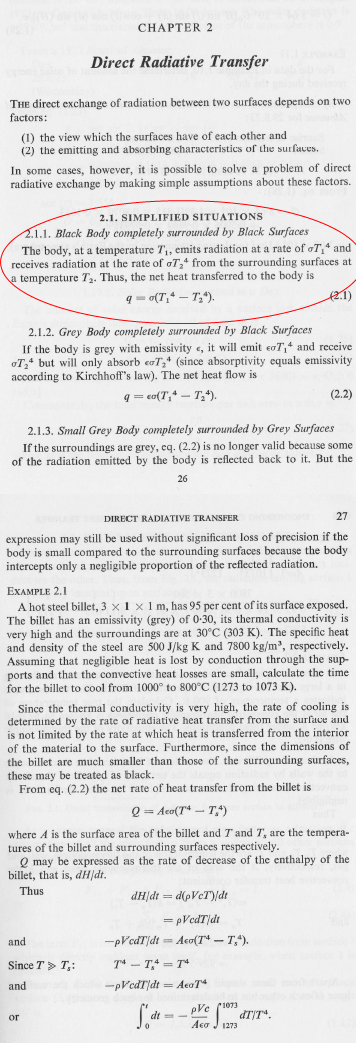

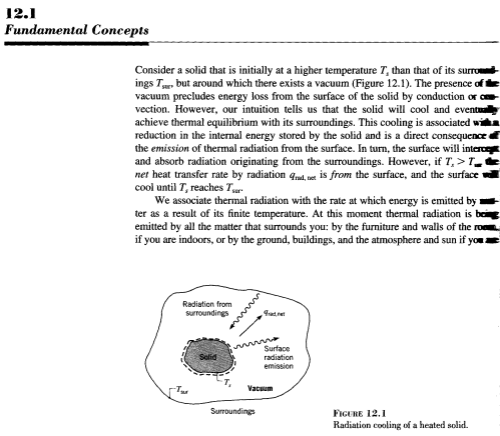

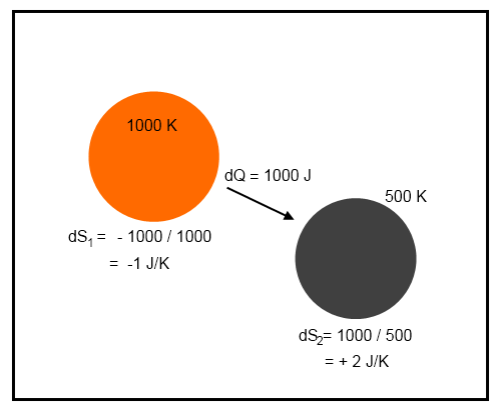

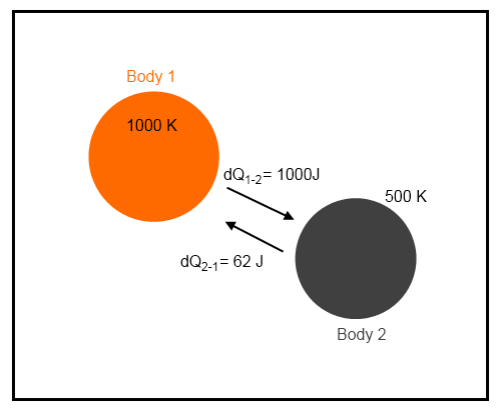

The first term on the right, σT4, is the Stefan-Boltzmann equation which calculates radiation from a surface from its temperature, e.g., for a 288K surface (15°C) the surface radiation = 390 W/m².

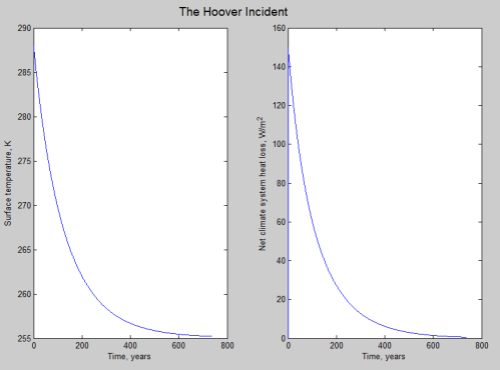

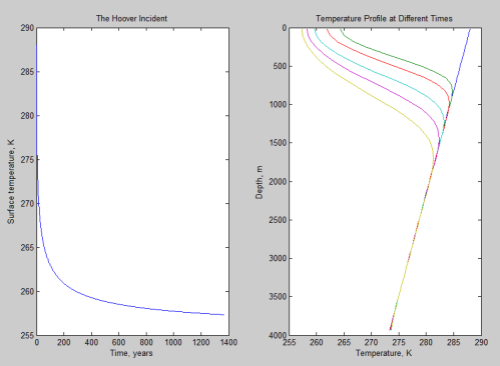

If the atmosphere had no radiative absorbers (no “greenhouse” effect) then F= σT4, which means G=0. See The Hoover Incident.

The approach Ramanathan took was to find out the actual climate response over 1988-89 from ERBE scanner data. What happens to the parameters F and G when temperature increases?

Why is it important?

If increasing CO2 warms the planet, will there be positive, negative or no feedback from water vapor? Apparently, Ramanathan thought that analyzing the terms in the equation under changing conditions could shed some light on the subject.

However, the equation itself was brought into question, mainly by Colin Davidson, in a number of comments including:

..In the section “Greenhouse Effect and Water Vapour”, he introduces an equation:

F = σTs^4 – G

I didn’t understand what this equation was trying to say. How are the Surface Radiation and the Outgoing Long Range Radiation linked, noting that there are other fluxes from the Surface into the Atmosphere? And one of these (evaporation) is stronger than the NET Surface radiation, while direct Conduction is also a significant flux?

The sentence “So the radiation from the earth’s surface less the “greenhouse” effect is the amount of radiation that escapes to space.” is not accurate.

Missing from this sentence are the following:

Incoming Solar Radiation Absorbed by the Atmosphere(A);

Evaporated Water from the Surface(E);

Direct Conduction from Surface to Atmosphere(C)

Back-Radiation from Atmosphere to Surface (B)

Writing down the fluxes for the atmosphere as a black box:

F= A+(S-B)+E+C (where S=Stephan-Boltzmann Surface Radiation),

Making G = S-F = B-A-E-C

So G doesn’t appear to me to make much PHYSICAL sense, and is certainly NOT the “Greenhouse Effect”, as the evaporative and conductive species are not greenhouse animals, but B and A certainly belong in the zoo..

And:

..I have shown that both those claims are incorrect. G does not represent the “Greenhouse” effect of an IR active atmosphere, as it contains terms (Evaporation and Conduction) which are plainly IR insensitive, nor does it represent the upward surface flux less the amount of longwave radiation leaving the planet.

What G represents is anyone’s guess, but it is not an easily identifiable physical quantity.

Hence my problem with the equation F=S-G as a starting point for any analysis – it doesn’t seem to represent anything coherent. Why not start with the TOA balance, the Surface balance, or the Atmospheric balance?

I am concerned about this. Is the whole theorem of climate sensitivity based on the incorrect notion that the factor G represents the Greenhouse Effect?

As well as:

In this post I summarise some of my concerns.

1. F= Sunlight – Reflected sunlight. Unless the earth’s short-wave albedo changes, the Outgoing Long-Wave Radiation(F) is constant, whatever the state of the Greenhouse. So dF/dTs does not represent the Greenhouse Effect, but is a representation of the change of surface temperature with cloudiness.

2. F= S(urface Radiation) + G, but G= E(vaporation) +C(onduction) + A(bsorbed Solar Radiation) – B(ack Radiation). Of these terms, only A and B are Greenhouse dependent. C and E are Greenhouse independent. dG/dTs is therefore not a measure of the Greenhouse Effect.

3. It is unclear if the amount of radiation from the surface escaping “through the window” direct to space is constant. If CO2 concentration increases we expect some tightening of the window, but not much. On the other hand any increase in surface temperature will increase the amount of radiation, so the two processes may balance. Kiehl and Trenberth keep this constant at 40W/m^2 despite raising the surface temperature over time by 1DegC, suggesting that it may be close to constant.

Assuming that is so, the fluxes warming the atmosphere from the Surface are constant, the (B)ack radiation increasing by roughly the same as the sum of the increases in Radiation from the Surface(S) and (E)vaporation. Basically when the surface temperature increases, the increase in Evaporation is balanced by a

decrease in Net Surface Radiation Absorbed by the Atmosphere.

As the heat entering the lower atmosphere is unchanged (though the amounts entering at each height will change), the overall Lapse Rate to the tropopause will be unchanged. So the temperature at the Tropopause will always be the Surface Temperature minus a Constant. The sensitivity of the Tropopause temperature is therefore the same as (and driven by) the sensitivity of the Surface temperature to changes in “forcing” (either solar or back-radiation).

This sensitivity is between 0.095 and 0.15 DegC/W/m^2.

And a search in that post will highlight all the other comments.

My attempts at explaining the concept did not appear successful. I don’t think I will have any more success this time, but clearly others think it is important.

I find Colin’s comments confused, but I’ll start with the main point of Ramanathan (paraphrased by me):

What happens if the climate warms from CO2 (or solar or any other cause) – will water vapor in the climate increase, causing a larger “greenhouse” effect?

That’s the question that many people have asked. These people include well-known figures like Richard Lindzen and Roy Spencer, who believe that negative feedbacks dominate.

Scenarios to Demonstrate the Usefulness of the Definition

If the surface temperature in one location goes from 288K (15°C) to 289K (16°C) the surface radiation will increase by 5.4 W/m². (The Stefan-Boltzmann law). How can we determine whether positive or negative feedbacks exist?

Condition 1. Suppose under clear skies when the temperature was 288K we measured OLR = 265 W/m² and when the temperature increased to 289K we measured OLR = 275 W/m². That means OLR has increased by 10 W/m² for a surface radiation increase of 5.4 W/m². Let’s call this condition Good.

Condition 2. Suppose instead that when the temperature increased to 289K we measured OLR = 265W/m². That means OLR has not changed when surface radiation increased by 5.4 W/m². Let’s call this condition Bad.

- In condition Good we have negative feedback, where the atmospheric “greenhouse” response to higher temperatures is to reduce its absorption of longwave radiation

- In condition Bad we have positive feedback – the situation where more heat has been trapped by the atmosphere – the atmosphere has increased its absorption of longwave radiation

Whether or not more heat also leaves the surface by evaporation or conduction doesn’t really matter for this analysis. It doesn’t tell us what we need to know.

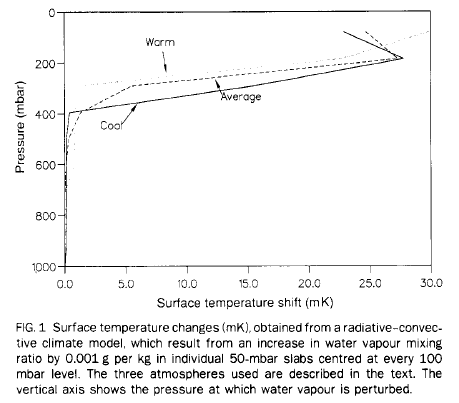

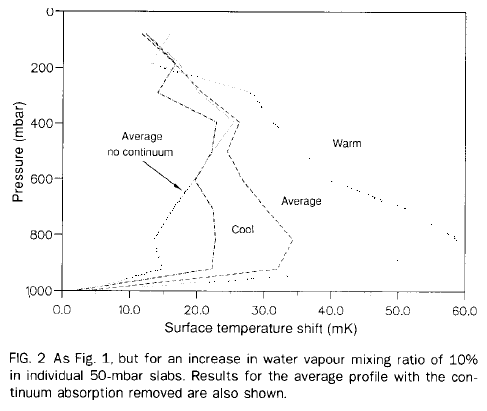

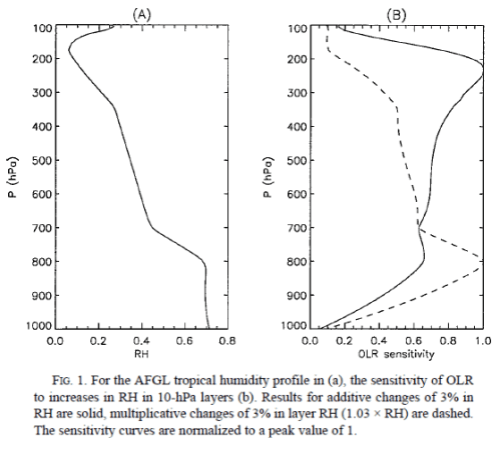

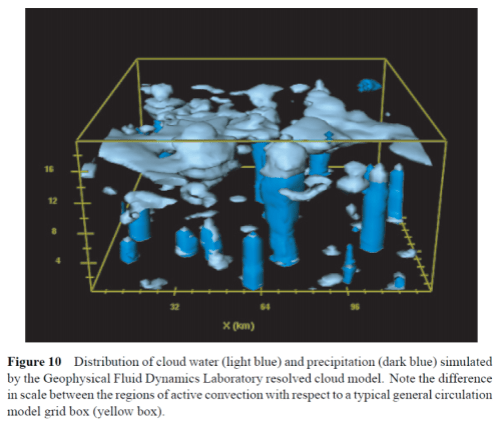

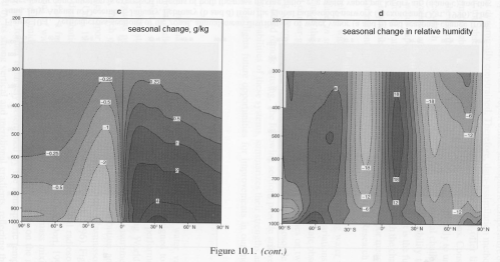

In fact, it’s quite likely that if evaporation increases we might find that positive feedback exists. However, that depends on exactly where the water vapor ends up in the atmosphere (as the absorption of longwave radiation by water vapor is non-linear with height) and how this also changes the lapse rate (as the moist lapse rate is less than the dry lapse rate).

It’s possible that if convective heat fluxes from the surface increase we might find that negative feedback exists – this is because heat moved from the surface to higher levels in the atmosphere increases the ability of the atmosphere to radiate out heat. This is also part of the lapse rate feedback.

But all of these different effects are wrapped up in the ultimate question of how much heat leaves the top of atmosphere as a function of changes in the surface temperature. This is what feedback is about.

So for feedback we really want to know – does the absorptance of the atmosphere increase as surface temperature increases? (see note 3).

That’s as much as I can explain as to why this measure is the useful one for understanding feedback. This is why everyone that deals with the subject reviews the same fundamental equation. This includes those who believe that negative feedbacks dominate.

See Note 2 and Note 3.

Colin Davidson’s points

Colin often makes very sensible statements and points but many of the statements and claims cited earlier suffer from irrelevance, inaccuracy or a lack of any proof.

Missing the point – as I described above – was the main problem. In the interests of completeness we will consider some of his statements.

The third comment cited above indicates one of the main problems with his approach:

..Unless the earth’s short-wave albedo changes, the Outgoing Long-Wave Radiation(F) is constant, whatever the state of the Greenhouse. So dF/dTs does not represent the Greenhouse Effect..

This is not the case. Suppose that absorbed solar radiation is constant. This does not mean that OLR (=”F” in Colin’s description) will be constant. From the First Law of Thermodynamics:

Energy in = Energy out + energy added to the system

In long term equilibrium energy in = energy out. However, we want to know what happens if something disturbs the system. For example, if increased CO2 reduces OLR then heat will be added to the climate system until eventually OLR rises to match the old value – but with a higher temperature in the climate. The same is the case with any other forcing. (See The Earth’s Energy Budget – Part Two).

In fact we expect that for a particular location and time OLR won’t equal solar radiation absorbed. We also have the problem that any “out of equilibrium” signal we might try to measure at TOA is very small, and within the error bars of our measuring equipment.

I didn’t understand what this equation was trying to say. How are the Surface Radiation and the Outgoing Long Range Radiation linked, noting that there are other fluxes from the Surface into the Atmosphere? And one of these (evaporation) is stronger than the NET Surface radiation, while direct Conduction is also a significant flux?

This is a very basic point. The surface radiation and outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) are linked by the equations of atmospheric absorption and emission (see note 4). With no absorption, OLR = surface radiation. The more the concentration of absorbers in the atmosphere the greater the difference between surface radiation and OLR. If we want to find out the feedback effect of water vapor this is exactly the relationship we need to study. Surface radiation and OLR are linked by the very effect we want to study.

A similar problem is suggested in the second comment cited:

..Hence my problem with the equation F=S-G as a starting point for any analysis – it doesn’t seem to represent anything coherent. Why not start with the TOA balance, the Surface balance, or the Atmospheric balance?

How is it possible to extract positive or negative feedback from these?

We expect that at TOA and at the surface the long term global annual average will balance to zero. But we can’t easily measure evaporation or sensible heat. Without carefully placed pyrgeometers we can’t measure DLR (downward longwave radiation) and without pyranometers we can’t measure the incident solar radiation at the surface. In any case even if we had all of these terms it doesn’t help us extract the sign or magnitude of the water vapor feedback.

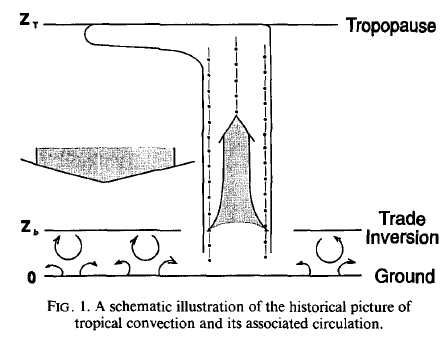

If we had lots of measurement capability at a particular location it might help us to estimate the evaporation. But then we have the problem of where does this water vapor end up? This is a problem that Richard Lindzen has frequently made – and is also made by Held & Soden in their review article (cited in Part Two). Approaching the problem (from the surface energy balance) without knowing the answer to where water vapor ends up we can’t attempt to calculate the sign of water vapor feedback.

Colin also makes a number of other comments of dubious relevance in the last section of text I extracted.

He states that evaporation and conduction are “greenhouse independent” – but I question this. More “greenhouse” gases mean more surface irradiation from the atmosphere, and therefore more evaporation and conduction (and convection).

The amount of radiation escaping through the so-called “atmospheric window” is not constant (perhaps a subject for a later article). The rest of the statement covers the belief in some kind of simplified atmospheric model where everything is in balance – and therefore a positive feedback is defined out of existence:

Basically when the surface temperature increases, the increase in Evaporation is balanced by a decrease in Net Surface Radiation Absorbed by the Atmosphere.

As the heat entering the lower atmosphere is unchanged (though the amounts entering at each height will change), the overall Lapse Rate to the tropopause will be unchanged. So the temperature at the Tropopause will always be the Surface Temperature minus a Constant. The sensitivity of the Tropopause temperature is therefore the same as (and driven by) the sensitivity of the Surface temperature to changes in “forcing” (either solar or back-radiation).

When surface temperature increases, evaporation is not balanced by a decrease in net surface radiation absorbed by the atmosphere. In fact, when surface temperature increases, surface radiation increases and possible atmospheric absorption of this radiation increases (due to humidity increases from more evaporation). Exactly what change this brings in DLR (atmospheric radiation received by the surface) is a question to be answered. By saying everything is in balance means that the solution about positive feedback is already known. If so, this needs to be demonstrated – not claimed.

The rest of the statement above suffers from the same problem. None of it has been demonstrated. If I understand it at all, it’s kind of a claim of climate equilibrium which therefore “proves” (?) that there isn’t water vapor feedback. However, I don’t really understand what it might demonstrate.

Other Comments Needing Response from the Original Article

From Leonard Weinstein:

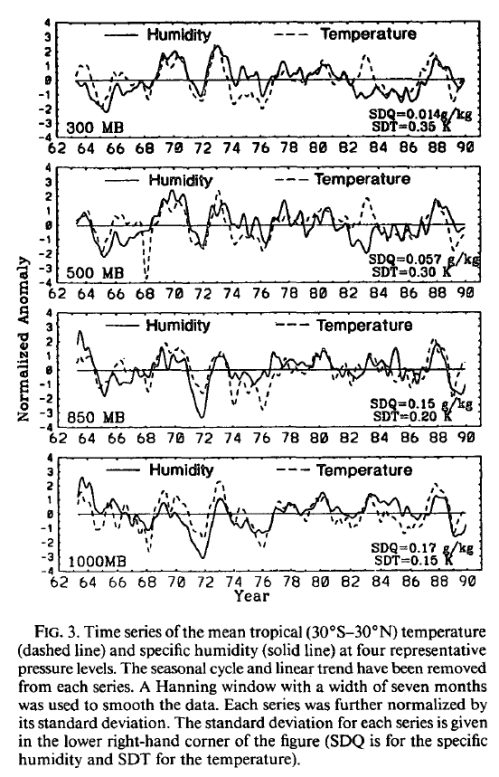

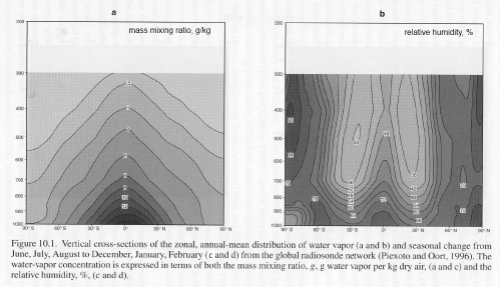

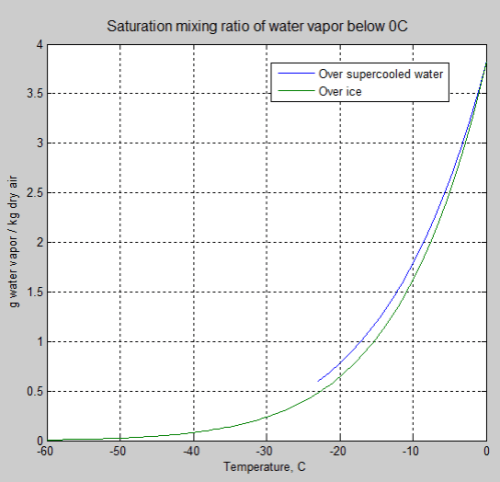

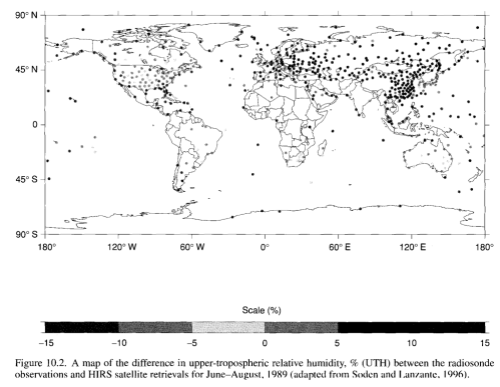

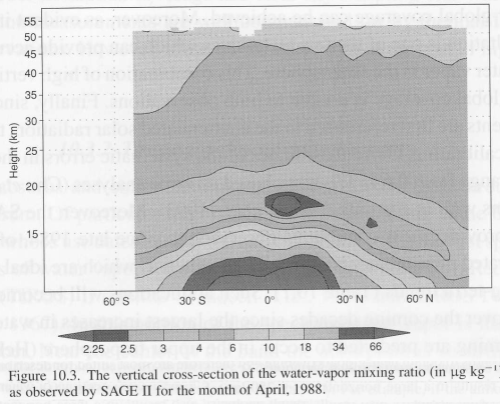

Since the issue is not resolved that the temperature in the upper troposphere has increased, and the relative humidity has not stayed nearly constant (it has clearly decreased) over the period of greatest lower troposphere temperature increase, the argument seems less than resolved. The lack of increased water vapor in the stratosphere pushes that point even further.

The argument isn’t resolved by this piece of work. This is one attempt to measure the effect over a period of good quality data.

Finely, the data and analysis of Roy Spencer seems to lead to different conclusions even on the data interpretation. Can you point out his errors and respond to those issues?

Roy Spencer’s analysis doesn’t address this period of measurement. His paper is about the period from 2000-2008.

From NicL:

However, I take issue with your statement “It should be clear from these graphics that observed variations in the normalized “greenhouse” effect are largely due to changes in water vapor.” The spatial maps referred to merely indicate a correlation between these two things. It is unscientific to infer causation from correlation. Ramathan himself goes no further than to say the graphics suggest that variations in water vapour rather than lapse rates contribute to regional variations in the greenhouse effect.

It’s unscientific to infer causation from correlation in the absence of a theory that links them together. It’s solidly established that water vapor absorbs longwave radiation from the surface, and it’s solidly established that CO2 and other “greenhouse” gases are well-mixed through the atmosphere, while water vapor is not. Therefore, there is a strong theoretical link.

I think, in common with various other repondants, that changes in lapse rates and in the height of the tropopause are key issues in modelling the greenhouse effect, yet they seem rarely discussed. Ramanathan’s chapter does not really cover them.

What makes you say they are rarely discussed? There are many papers discussing the different processes involved in modeling water vapor feedback. However, Ramanathan’s chapter is primarily about measurements. Of course he refers to the different aspects of feedback in the chapter.

Conclusion

One commenter in part two said:

I want to give him a chance to reflect on whether he wants to defend the Ramanathan analysis in Part 1 or separate himself with dignity, which he can still do..

The primary question seemed to be the approach, and not the results, of Ramanathan.

Ramanathan tested the changes in atmospheric absorptance of longwave radiation with temperature changes. To claim this is inherently wrong is a bold claim and one I can’t understand. Neither can Richard Lindzen or Roy Spencer, at least, not from anything I have read of their work.

There are other possible approaches to Ramanathan’s results. Other researchers may have replicated his work and found different results. Other researchers may have analyzed different periods and found different changes.

There are also theoretical considerations – whether changes in the equilibrium temperature as a result of increased CO2 can be considered as the same conditions under which seasonal changes indicated positive water vapor feedback.

The question for readers to ask is: Did Ramanathan find something important that needs to be considered?

Ramanathan himself said:

However, our results do not necessarily confirm the positive feedback resulting from the fixed relative humidity models for global warming, for the present results are based on annual cycle.

If I someone can point out the theoretical flaw in Ramanathan’s work then I might “separate myself with dignity” otherwise I will be happy to stand by the idea that he has demonstrated something that needs to be considered.

Articles in this Series

Part One – introducing some ideas from Ramanathan from ERBE 1985 – 1989 results

Part Two – some introductory ideas about water vapor including measurements

Part Three – effects of water vapor at different heights (non-linearity issues), problems of the 3d motion of air in the water vapor problem and some calculations over a few decades

Part Four – discussion and results of a paper by Dessler et al using the latest AIRS and CERES data to calculate current atmospheric and water vapor feedback vs height and surface temperature

Part Five – Back of the envelope calcs from Pierrehumbert – focusing on a 1995 paper by Pierrehumbert to show some basics about circulation within the tropics and how the drier subsiding regions of the circulation contribute to cooling the tropics

Part Six – Nonlinearity and Dry Atmospheres – demonstrating that different distributions of water vapor yet with the same mean can result in different radiation to space, and how this is important for drier regions like the sub-tropics

Part Seven – Upper Tropospheric Models & Measurement – recent measurements from AIRS showing upper tropospheric water vapor increases with surface temperature

Note 1.

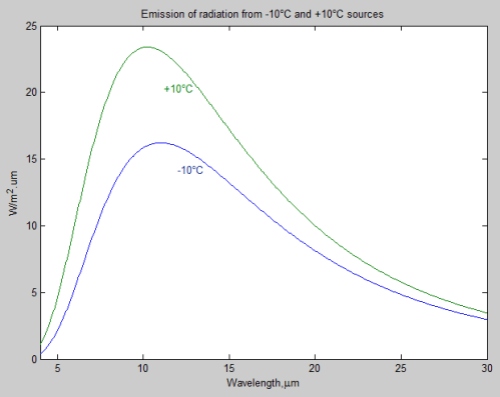

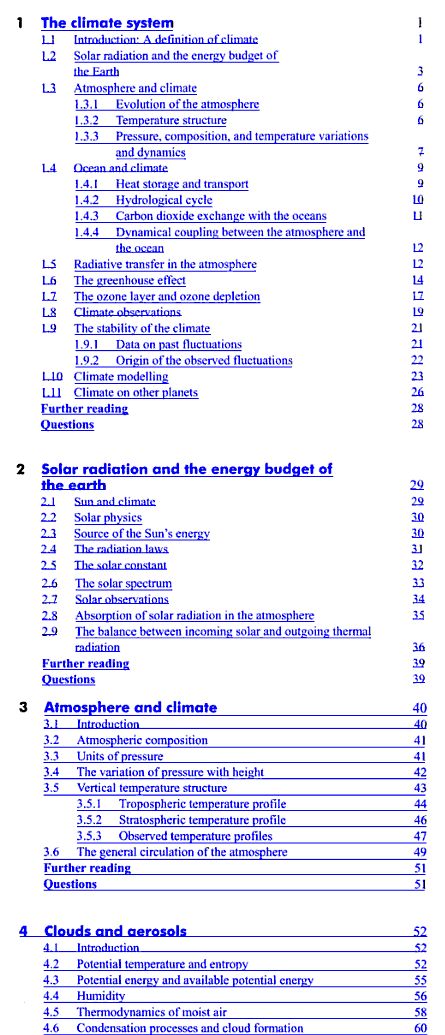

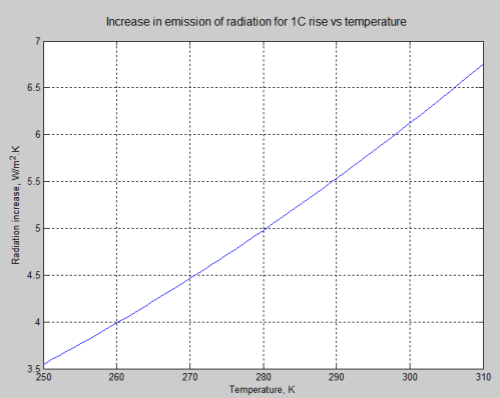

The actual change in emission of radiation for a 1°C rise in temperature depends on the temperature itself, one of the many non-linearities in science. The example in the article was for the specific temperature of 288K, along with the desire to avoid confusing readers with too many caveats.

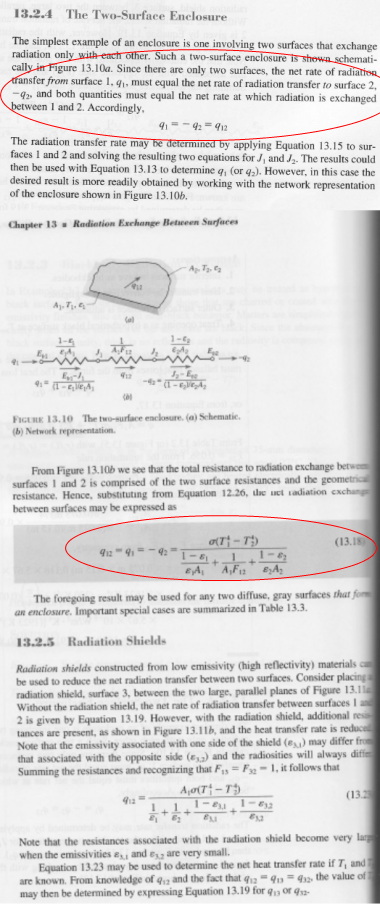

Here is the graph of radiation change for a 1°C rise vs temperature:

For the mathematicians it is an easy exercise. For non-mathematicians, the change in radiation = 4σT³ W/m².K (obtained by differentiating the Stefan-Boltzmann equation with respect to T).

Note 2.

This article is about a specific point in Ramanathan’s work queried by some of my readers. His explanation of how to determine feedbacks is much more lengthy and includes some important points, especially the demonstration of the relationships in time between the various changes. These are important for the determination of cause and effect. See the original article and especially the online chapter for more a detailed explanation.

Note 3.

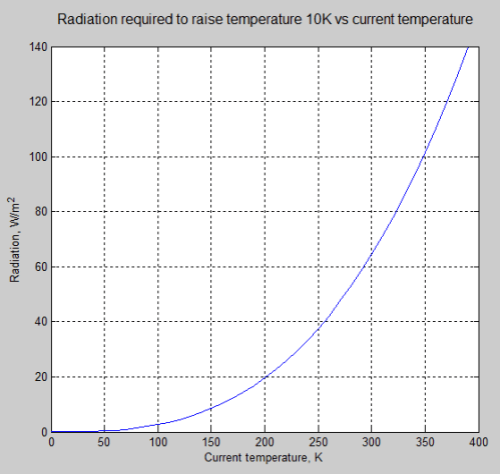

The rate of change of surface radiation with temperature, σdT4/dT = 4σT³ W/m².K (see note 1) is 5.4W/m² per K at 288K. However, the rate of change of OLR, dF/dT, for the no feedback condition is slightly more challenging to determine and not intuitively obvious.

Ramanathan, based on his earlier work from 1981, determined the “no feedback” condition (i.e., without lapse-rate feedback or water vapor feedback) was dF/dT=3.3 W/m².K. And for positive feedback this parameter, dF/dT would be less than 3.3.

Roy Spencer and William Braswell in their just-published work in JGR, On the diagnosis of radiative feedback in the presence of unknown radiative forcing has exactly the same value as the determination of the no feedback condition.

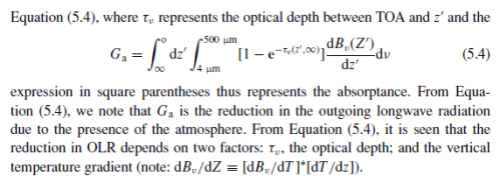

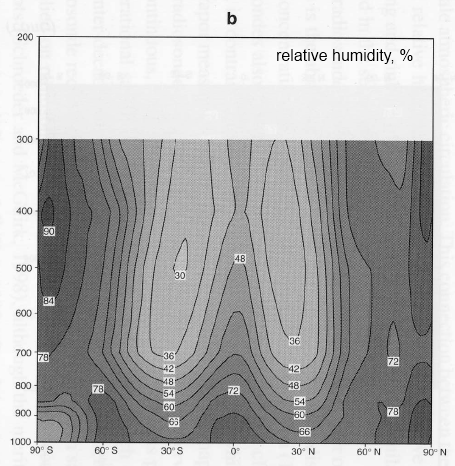

Note 4.

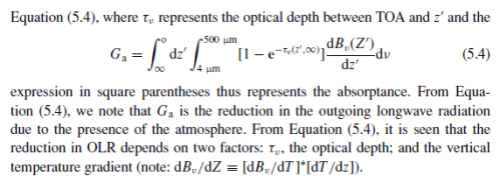

There are many different formulations of the solutions to the radiative transfer equations. This version is from Ramanathan’s chapter in Frontiers of Climate Modeling:

This is just to demonstrate that there is a strong mathematical link between surface radiation and OLR, and one that is very relevant for determining whether positive or negative feedbacks exist.