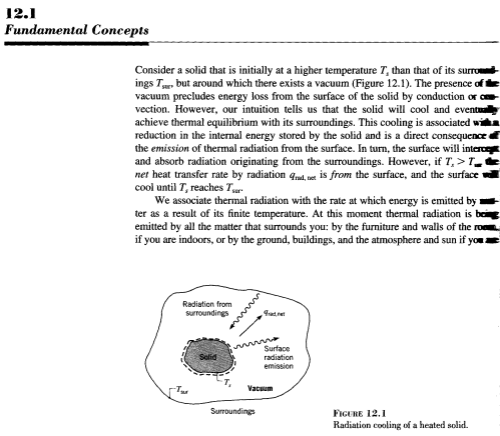

During a discussion about Venus (Venusian Mysteries), Leonard Weinstein suggested a thought experiment that prompted a 2nd article of mine. Unfortunately, it really failed to address his point.

In fact, it took me a long time to get to grips with Leonard’s point and 500 comments in (!) I suggested that we write a joint article.

I also invited Arthur Smith who probably agrees mostly with me, but at times he was much clearer than I was. And I’m not sure we are totally in agreement either. I did offer Leonard the opportunity to have another contributor on his side, but he is happy to write alone – or draw on one of the other contributors in forming his article. The format here is quite open.

The plan is for me to write the first section, and then Arthur to write his, followed by Leonard. The idea behind it is to crystallize our respective thoughts so that others can review them, rather than wading through 500+ comments. What was the original discussion about?

It’s worth repeating Leonard Weinstein’s original thought experiment:

Consider Venus with its existing atmosphere, and put a totally opaque enclosure (to incoming Solar radiation) around the entire planet at the average location of present outgoing long wave radiation. Use a surface with the same albedo as present Venus for the enclosure. What would happen to the planetary surface temperature over a reasonably long time? For this case, NO Solar incoming radiation reaches the surface. I contend that the surface temperature will be about the same as present..

Those who are interested in that debate can read the complete idea and the many comments that followed. During the course of our debate we each posed different thought experiments as a means to finding the flaws in the various ideas.

At times we lost track of which experiment was being considered. Many times we didn’t quite understand the ideas that were posed by others.

And therefore, before I start, it’s worth saying that I might still misrepresent one of the other points of view. But not intentionally.

Introductory Ideas – Pumping up a Tyre

This first section is uncontroversial. It is simply aimed at helping those unfamiliar with terms like adiabatic expansion. Unfortunately, it will be brief with more Wikipedia links than usual.. (if there are many questions on these basics then I might write another article).

So let’s consider pumping up a bicycle tire. When you do pump up a tire you find that around the valve everything can get pretty hot. Why is that? Does high pressure cause high temperature? Let’s review two idealized ways of compressing an ideal gas:

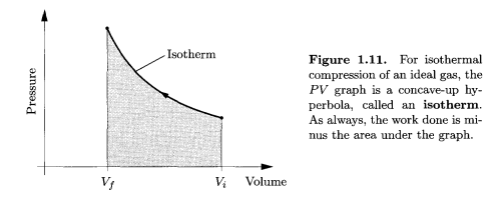

- isothermal compression – which is so slow that the temperature of the gas doesn’t rise

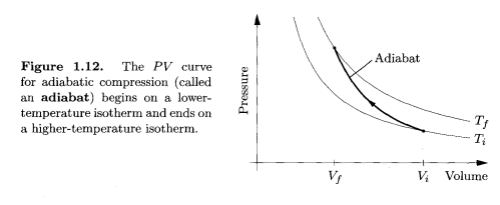

- adiabatic compression – which is so fast that no heat escapes from the gas during the process

Pressure and volume of a gas are inversely related if temperature is kept constant – this is Boyle’s law

.

Imagine pumping up a tire very very slowly. Usually this isn’t possible because the valve leaks.

If it was possible you would find that the work done in compressing the gas didn’t increase the gas temperature because the heat increase in the gas would equalize out to the wheel rims and to the surrounding atmosphere.

Now imagine pumping up a tire very quickly. The usual way. In this case, you are adding energy to the system and there is no time for the temperature to equalize with the surroundings, so the temperature increases (because work is done on the gas):

The ideal gas laws can be confusing because three important terms exist in the one equation, pressure, volume and temperature:

PV = nRT or PV = NkT

where P = pressure, V = volume, T = absolute temperature (in K), N = number of molecules and k = Boltzmann’s constant

So the two examples above give the two extremes of compression. One, the isothermal case, has the temperature held constant because the process is very slow, and one, the adiabatic case, has the energy leaving the system being zero because the process is so fast.

In a nutshell, high pressures do not, of themselves, cause high temperatures. But changing the pressure – i.e., compressing a gas – does increase the temperature if it is done quickly.

Introductory Ideas – The “Environmental Lapse Rate” and Convection

Equally importantly, adiabatic expansion reduces the temperature in a gas.

If you lift air up in the atmosphere quickly then it will expand and cool. In dry air, some simple maths calculates this expansion as a temperature drop of just under 10K per km. In very moist air, this temperature drop can be as low as 4K per km. (The actual value depends on the amount of moisture).

Imagine the (common) situation where due to pressure effects a “parcel of air” is pushed upwards a small way, say 100m. Under adiabatic expansion, the temperature will drop somewhere between 1K (1°C) for dry air and 0.4K for very moist air.

Suppose that the actual atmospheric temperature profile is such that the temperature 100m higher up is 1.5K cooler. (We would say that the environmental lapse rate was 15K/km).

In this case, the parcel of air pushed up is now warmer than the surrounding air and, therefore, less dense – so it keeps rising. This is the major idea behind convection – if the environmental lapse rate is “more than” the adiabatic lapse rate then convection will redistribute heat. And if the environmental lapse rate is “less than” the lapse rate then the atmosphere tends to be stable against convection.

Note – the terminology can be confusing for newcomers. Even though temperature decreases as you go up in the atmosphere the adiabatic lapse rate is written as a positive number. Just imagine that the temperature in the atmosphere actually decreases by 1K per km and think what happens if the adiabatic lapse rate is 10K per km – air that is lifted up will be much colder than the surrounding atmosphere and sink back down.

Now imagine that the temperature decreases by 15K per km and think what happens if the adiabatic lapse rate is 10K per km – air that is lifted up will be much warmer than the surrounding atmosphere (so will expand and be less dense) and will keep rising.

All of this so far described is uncontentious..

The Main Contention

Armed with these ideas, the main contentious point from my side was this:

If you heat a gas sufficiently from the bottom, convection will naturally take place to redistribute heat. The environmental “lapse rate” can’t be sustained at more than the adiabatic lapse rate because convection will take over. This is the case with the earth, where most of the solar radiation is absorbed by the earth’s surface.

But if you heat a gas from the top (as in the original proposed thought experiment) then there is no mechanism to create the adiabatic lapse rate. This is because there is no mechanism to create convection. So we can’t have an atmosphere where the environmental lapse rate is greater than the adiabatic lapse rate – but we can have one where it is less.

Convection redistributes heat because of natural buoyancy, but convection can’t be induced to work the other way.

Well, maybe it’s not quite as simple..

The Very Tall Room Full of Gas

Leonard suggested – Take an empty room 1km square and 100km high and pour in gas at 250K from the top. The gas doesn’t absorb or emit any radiation. What happens?

The gas is adiabatically compressed (due to higher pressure below) and the gas at the bottom ends up at a much higher temperature.

Another way to think about adiabatic compression is that height (potential energy) is converted to speed (kinetic energy) because of gravity – like dropping a cannon ball.

We all agree on that – but what happens afterwards? (And I think we were all assuming that a lid is placed over the top of the tall room and the lid effectively stays at a temperature of 250K due to external radiation – however, no precise definition of the temperature of the room’s walls and lid was made).

My view – over a massively long time the temperature at the top and bottom will eventually reach the same value. This seemed to be the most contentious point.

However, in saying that, there was a lot of discussion about exactly the state of the gas so at times I wondered whether it was fundamental thermodynamics up for discussion or not understanding each other’s thought experiments.

In making this claim that the gas will become isothermal (all at the same temperature), I am assuming that the gas will eventually be stationary on a large scale (obviously the gas molecules move as their temperature is defined by their velocity). So all of the bulk movements of air have stopped.

Conduction of heat is left as the only mechanism for movement of heat and as gas molecules collide with each other they will all eventually reach the same temperature – the average temperature of the gas. (Because external radiation to and from the lid and walls wasn’t defined this will affect what final average value is reached). Note that temperature of a gas is a bulk property, so a gas at one temperature has a distribution of velocities (the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution).

The Tall Room when Gases Absorb and Emit Radiation

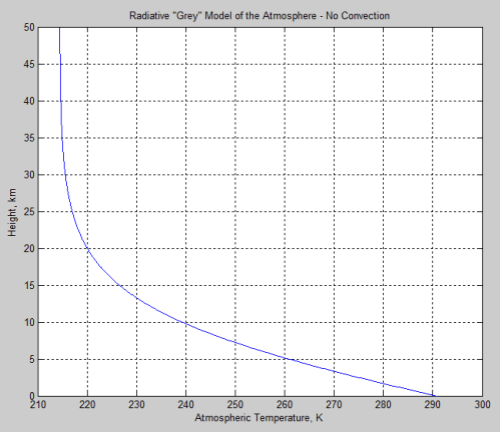

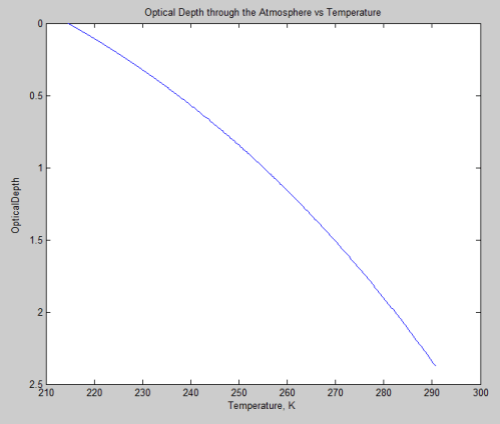

We all appeared to agree that in this case (radiatively-absorbing gases) that as the atmosphere becomes optically thin then radiation will move heat very effectively and the top part of the atmosphere in this very tall room will become isothermal.

Heating from the Top

The viewpoint expressed by Leonard is that differential heating (night vs day, equatorial vs polar latitudes) will eventually cause large scale circulation, thus causing bulk movement of air down to the surface with the consequent adiabatic heating. This by itself will cause the environmental lapse rate to become very close to the adiabatic lapse rate.

I see it as a possibility that I can’t (today) disprove, but Leonard’s hypothesis itself seems unproven. Is there enough energy to drive this circulation when an atmosphere is heated from the top?

I found two considerations of this idea.

One was the Sandstrom theorem which considered heating a fluid from the bottom vs heating it from the top. More comment in the earlier article. I guess you could say Sandstrom said no, although others have picked some holes in it.

The other was in Atmospheres (1972) by the great Richard M. Goody and James C. Walker. In a time when only a little was known about the Venusian atmosphere, Goody & Walker suggested first that probably enough solar radiation made it to the surface to initiate heating from below (to cut a long story short). And later made this comment:

Descending air is compressed as it moves to lower levels in the atmosphere. The compression causes the temperature to increase.. If the circulation is sufficiently rapid, and if the air does not cool too fast by emission of radiation, the temperature will increase at the adiabatic rate. This is precisely what is observed on Venus.

Venera and Mariner Venus spacecraft have all found that the temperature increases adiabatically as altitude decreases in the lower atmosphere. As we explained this observation could also be the result of thermal convection driven by solar radiation deposited at the ground, but we cannot be sure that the radiation actually reaches the ground.

What we are now suggesting as an alternative explanation is that the adiabatic temperature gradient is related to a planetary circulation driven by heat supplied unevenly to the upper levels of the atmosphere. According to this theory, the high ground temperature is caused, at least in part, by compressional heating of the descending air.

In the specific case of the real Venus (rather than our thought experiments), much more has been uncovered since Goody and Walker wrote. Perhaps the question of what happens in the real Venus is clearer – one way or the other.

What do I conclude?

I’m glad I’ve taken the time to think about the subject because I feel like I understand it much better as a result of this discussion. I appreciate Leonard especially for taking the time, but also Arthur Smith and others.

Before we started discussing I knew the answers for certain. Now I’m not so sure.

_____________________________________________________________________

By Arthur Smith

First on the question of convective heat flow from heating above, which scienceofdoom just ended with: I agree some such heat flow is possible, but it is difficult. Goody and Walker were wrong if they felt this could explain high Venusian surface temperatures.

The foundation for my certainty on this lies in the fundamental laws of thermodynamics, which I’ll start by reviewing in the context of the general problem of heat flow in planetary atmospheres (and the “Very Tall Room Full of Gas”). Note that these laws are very general and based in the properties of energy and the statistics of large numbers of particles, and have been found applicable in systems ranging from the interior of stars to chemical solutions and semiconductor devices and the like. External forces like gravitational fields are a routine factor in thermodynamic problems, as are complex intermolecular forces that pose a much thornier challenge. The laws of thermodynamics are among the most fundamental laws in physics – perhaps even more fundamental than gravitation itself.

I’m going to discuss the laws out of order, since they are of various degrees of relevance to the discussion we’ve had. The third law (defining behavior at zero temperature) is not relevant at all and won’t be discussed further.

The First Law

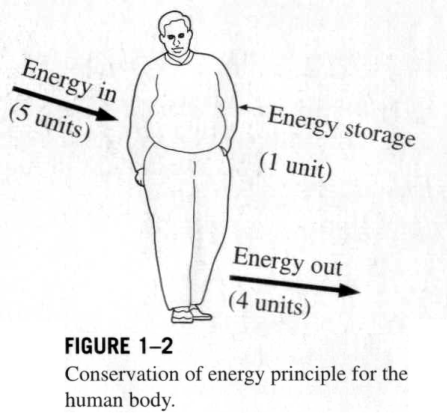

The first law of thermodynamics demands conservation of energy:

Energy can be neither created nor destroyed.

This means that in any isolated system the total energy embodied in the particles, their motion, their interactions, etc. must remain constant. Over time such an isolated system approaches a state of thermodynamic equilibrium where the measurable, statistically averaged properties cease changing.

In our previous discussion I interpreted Leonard’s “Very Tall Room Full of Gas” example as such a completely isolated system, with no energy entering or leaving. Therefore it should, eventually at least, approach such a state of thermodynamic equilibrium. Scienceofdoom above interpreted it as being in a condition where the top of the room was held at a given specific temperature. That condition would allow energy to enter and leave over time, but eventually the statistical properties would also stop changing, and then energy flow through that top surface would also cease, total energy would be constant, and you would again arrive at an equilibrium system (but with a different total energy from the starting point).

That would also be the case in Leonard’s original thought experiment concerning Venus if the temperature of the “totally opaque enclosure” was a uniform constant value. The underlying system would reach some point where its properties ceased changing, and then with no energy flow in or out, it would be effectively isolated from the rest of the universe, and in its own thermodynamic equilibrium. However, Leonard allows the temperature of his opaque enclosure to vary with latitude and time of day which means that strictly such a statistical constancy would not apply and the underlying atmosphere would not be completely in thermodynamic equilibrium. I’ll look at that later in discussing the restrictions imposed by the second law.

In a system like a planetary atmosphere with energy flowing through it from a nearby star (or from internal heat) and escaping into the rest of the universe, you are obviously not isolated and would not reach thermodynamic equilibrium. Rather, if a condition where averaged properties cease changing is reached, this is referred to as a steady state. Under steady state conditions the first law must still be obeyed. Since internal statistical properties are unchanging, that means the system must not be gaining or losing any internal energy. So in steady state you have a balance between incoming and outgoing energy from the system, enforced by the first law of thermodynamics.

If such an atmospheric system is NOT in steady state, if there is, say, more energy coming in than leaving, then the total energy embodied in the particles of the system will increase. That higher average energy per particle can be measured as an increase in temperature – but that gets us to the definition of temperature.

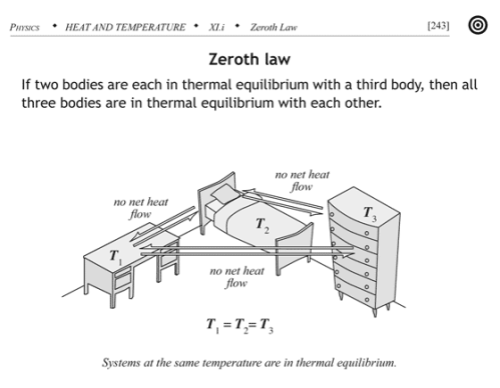

The Zeroth Law

The zeroth law essentially defines temperature:

If two thermodynamic systems are each in thermal equilibrium with a third, then they are in thermal equilibrium with each other.

Here thermal equilibrium means that when the systems are brought into physical proximity so that they may exchange heat, no heat is actually exchanged. A typical example of the zeroth law is to make the “third system” a thermometer, something that you can use to read out a measurement of its internal energy level. Any number of systems can act as a thermometer: the volume of mercury liquid in an evacuated bulb, the resistance of a strip of platinum, or the pressure of a fixed volume of helium gas, for example.

If you divide a system “A” in thermodynamic equilibrium into two pieces, “A1” and “A2”, and then bring those two into physical proximity again, no heat should flow between them, because no heat was flowing between them before separating them since neither one’s statistical properties were changing. I.e. Any two subsystems of a system in thermodynamic equilibrium must be in thermal equilibrium with each other. That means that if you place a thermometer to measure the temperature of subsystem “A1”, and find a temperature “T” for thermal equilibrium of the thermometer with “A1”, then subsytem “A2” will also be in thermal equilibrium with “T”, i.e. its temperature will also read out as the same value.

That is, the temperature of a system in thermodynamic equilibrium is the same as the temperature of every (macroscopic) subsystem – temperature is constant throughout. The zeroth law implies temperature must be a uniform property of such equilibrium systems.

This means that in both “Very Large Room” examples and for my version of Leonard’s original thought experiment for Venus (with a uniform enclosing temperature), the thermodynamic equilibrium that the atmosphere must eventually reach must have a constant and uniform temperature throughout the system. Temperature in the room or in the pseudo-Venus’ atmosphere would be independent of altitude – an isothermal, not adiabatic, temperature profile.

The zeroth law can actually be derived from the first and second laws – this is done for example in Statistical Physics, 3rd Edition Part 1, Landau and Lifshiftz (Vol. 5) (Pergamon Press, 1980) – Chapter II, Thermodynamics Quantities, Section 9 – “Temperature” – and again the conclusion is the same:

Thus, if a system is in a state of thermodynamic equilibrium, the [absolute temperature] is the same for every part of it, i.e. is constant throughout the system.

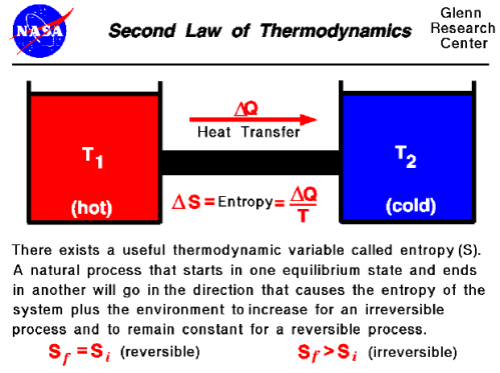

The Second Law

The first and zeroth laws tell us what happens in the cases where the atmosphere can be characterized as in thermodynamic equilibrium, i.e. actually or effectively isolated from the rest of the universe after sufficient period of time that quantities cease changing. Under those conditions it must have a uniform temperature. But what about Leonard’s actual Venus thought experiment, where there are constant fluxes of energy in and out due to latitudinal and time-of-day variations in the temperature of the opaque enclosure? What can we say about the temperatures in the atmosphere below given heating from above under those conditions? Here the second law provides the primary constraint, and in particular the Clausius formulation:

Heat cannot of itself pass from a colder to a hotter body.

A planetary atmosphere is not driven by machines that move the air around, there are no giant fans pushing the air from one place to another. There is no incoming chemical or electrical form of non-thermal energy that can force things to happen. The driving force is the flux of incoming energy from the local star that brings heat when it is absorbed. All atmospheric processes are driven by the resulting temperature differences. Thanks to the first law of thermodynamics each incoming chunk of energy can be accounted for as it is successively absorbed, reflected, re-emitted and so forth until it finally leaves again as thermal radiation to the rest of the universe. In each of these steps the energy is spontaneously exchanged from a portion of the atmosphere at one temperature to another portion at another temperature.

What the second law tells us, particularly in the above Clausius form, is that the net spontaneous energy exchange describing the flow of each chunk of incoming energy to the atmosphere MUST ALWAYS BE IN THE DIRECTION OF DECREASING TEMPERATURE. Heat flows “downhill” from high to low temperature regions. The incoming energy starts from the star – very high temperature. If it’s absorbed it’s somewhere in the atmosphere or the planetary surface, and from that point it must go through successfully colder and colder portions of the system before it can escape to space (where the temperature is 2.7 K).

There can be no net flow of energy from colder to hotter regions. And that means, if the atmosphere below Leonard’s “opaque enclosure” is at a higher temperature than any point on the enclosure, heat must be flowing out of the atmosphere, not inward. The enclosure, no matter the distribution of temperatures on its surface, cannot drive a temperature below it that is any higher than the highest temperature on the enclosure itself.

So even in the non-equilibrium case represented by Leonard’s original thought experiment, while the atmosphere’s temperature will not be everywhere the same, it will nowhere be any hotter than the highest temperature of the enclosure, after sufficient time has passed for such statistical properties to stop changing.

The thermodynamic laws are the fundamental governing laws regarding temperature, heat, and energy in the universe. It would be extraordinary if they were violated in such simple systems as these gases under gravitation that we have been discussing. Note in particular that any violation of the second law of thermodynamics allows for the creation of a “perpetual motion machine”, a device legions of amateurs have attempted to create with nothing but failure to show for it. Both the first and second laws seem to be very strictly enforced in our universe.

Approach to Equilibrium

The above results on temperatures apply under equilibrium or steady state conditions, i.e. after the “measurable, statistically averaged properties cease changing.” That may perhaps take a long time – how long should we expect?

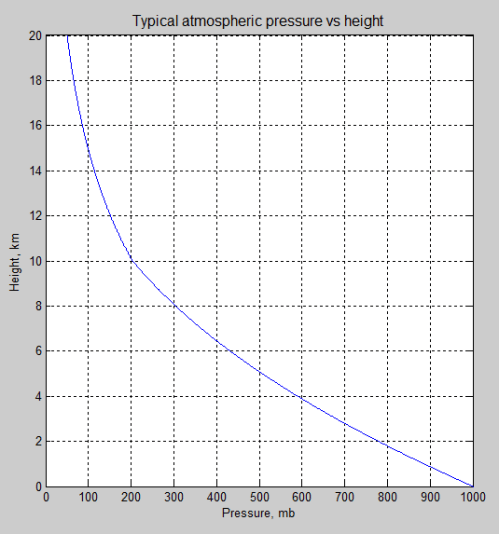

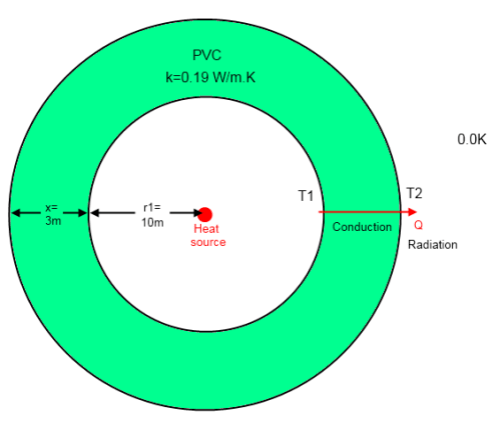

The heat content of a gas is given by the product of the heat capacity and temperature. For the Venus case we’re starting at 740 K near the surface and, under either of the “thought experiment” cases, dropping to something like 240 K in the end, about 500 degrees. Surface pressure on Venus is 93 Earth atmospheres, so in every square meter we have a mass of close to 1 million kg of atmosphere above it. [Quick calculation: 1 earth atmosphere = 101 kPa, or 10,300 kg of atmosphere per square meter, or 15 pounds per square inch. On Venus it’s 1400 pounds/sq inch.] The atmosphere of Venus is almost entirely carbon dioxide, which has a heat capacity of close to 1 kJ/kgK (see this reference). That means the heat capacity of the column of Venus’ atmosphere over 1 square meter is about one billion (109) J/K.

So a temperature change of 500 K amounts to 500 billion joules = 500 GJ for each square meter of the planetary surface. This is the energy we need to flow out of the system in order for it to move from present conditions to the isothermal conditions that would eventually apply under Leonard’s thought experiment.

Now from scienceofdoom’s previous post we expect at least an initial heat flow rate out of the atmosphere of 158 W/m² (that’s the outgoing flow that balances incoming absorption on Venus – since we’ve lost incoming absorption to the opaque shell, this ought to be roughly the initial net flow rate). Dividing this into 500 GJ/m² gives a first-cut time estimate for the cooling: 3.2 billion seconds, or about 100 years. So the cool-down to isothermal would be hardly immediate, but still pretty short on the scale of planetary change.

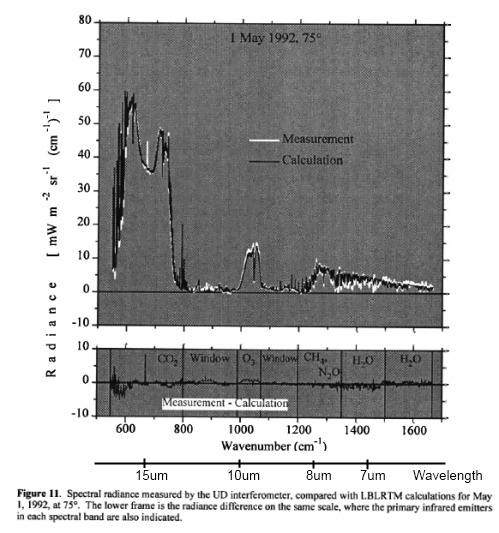

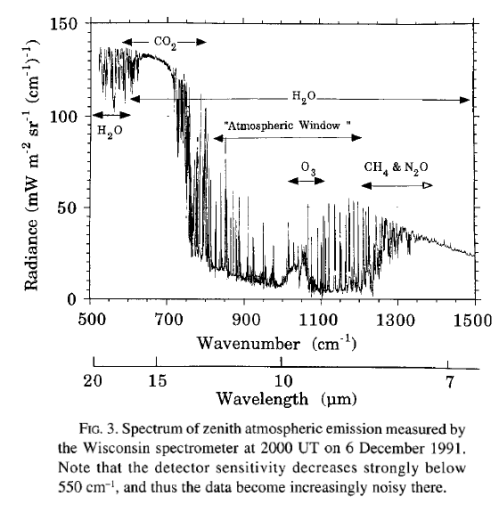

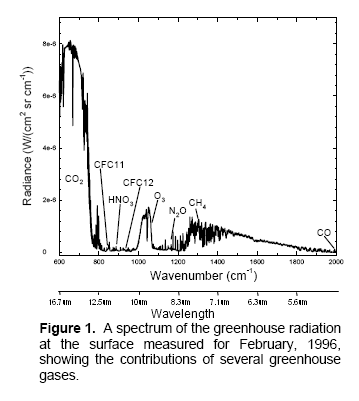

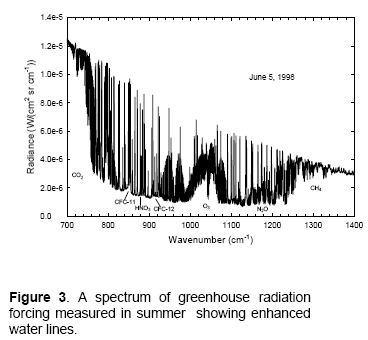

Now we shouldn’t expect that 158 W/m² to hold forever. There are four primary mechanisms for heat flow in a planetary atmosphere: conduction (the diffusion of heat through molecular movements), convection (movement of larger parcels of air), latent heat flow (movement of materials within air parcels that change phases – from liquid to gas and back, for example, for water) and thermal radiation. The heat flow rate for conduction is simply proportional to the gradient in temperature. The heat flow rate for radiation is similar except for the region of the atmospheric “window” (some heat leaves directly to space according to the Planck function for that spectral region at that temperature). Latent heat flow is not a factor in Venus’ present atmosphere, though it would come into play if the lower atmosphere cooled below the point where CO2 liquefies at those pressures.

For convection, however, average heat flow rates are a much more complex function of the temperature gradient. Getting parcels of gas to displace one another requires some sort of cycle where some areas go up and some down, a breaking of the planet’s symmetry. On Earth the large-scale convective flows are described by the Hadley cells in the tropics and other large-scale cells at higher latitudes, which circulate air from sea level to many kilometers in altitude. On a smaller scale, where the ground becomes particularly warm then temperature gradients exceeding the adiabatic lapse rate may occur, resulting in “thermals”, local convective cells up to possibly several hundred meters. If the temperature difference between high and low altitudes is too low, the convective instability vanishes and heat flow through convection becomes much weaker.

So as temperatures come closer to isothermal in an atmosphere like Venus’, except for the atmospheric “window” for radiative heat flow, we would expect all the heat flow mechanisms to decrease, and convection in particular to almost cease after the temperature difference gets too small. So we might expect the cool-down to isothermal conditions to slow down and end up much longer than this 100-year estimate. How long?

Another of the thought experiment versions discussed in the previous thread involved removing radiation altogether; with both radiation and convection gone, that leaves only conduction as a mechanism for heat flow through the atmosphere. For an ideal gas the thermal conductivity increases as the 2/3 power of the density (it’s proportional to density times mean free path) and the square root of temperature (mean particle speed). While CO2 is not really ideal at 93 atmospheres at 740 K, using this rule gives us a rough idea of what to expect – at 1 atmosphere and 273 K we have a value of 14.65 mW/(m.K) so at 93 atmospheres and 740 K it should be about 500 mW/(m . K). For a temperature gradient of 10 K/km that gives a heat flux of 0.005 W/m². 500 GJ would then take about 1014 seconds, or 3 million years.

So the approach to an isothermal equilibrium state for these atmospheres would take between a few hundred and a few million years, depending on the conditions you impose on the system. Still, the planets are billions of years old, so if heating from above was really the mechanism at work on Venus we should see the evidence of it in the form of cooler surface temperatures there by now, even if radiative heat flow were not a factor at all.

The View From a Molecule

Leonard in our previous discussion raised the point that an individual molecule sees the gravitational field, causing it to accelerate downwards. So molecular velocities lower down should be higher than velocities higher up, and that means higher temperatures.

Leonard’s picture is true of the behavior of a molecule in between collisions with the other molecules. But if the gas is reasonably dense, the “mean free path” (the average distance between collisions) becomes quite short. At 1 atmosphere and room temperature the mean free path of a typical gas is about 100 nanometers. So there’s very little distance to accelerate before a molecule would collide with another; to consider the full effect you need to look at the effect of collisions due to gas pressure along with the acceleration by gravity.

An individual molecule in a system in thermodynamic equilibrium at temperature T has available a collection of states in phase space (position, momentum and any internal variables) each with some energy E. In the case of our molecule in a gravitational field, that energy consists of the kinetic energy ½mv² (m = mass, v = velocity) plus the gravitational potential energy = gmz (where z = height above ground). The Boltzmann distribution applies in equilibrium, so that the probability of the molecule being in a state with energy E is proportional to:

e(-E/kT) = e(-(½mv² + gmz)/kT).

So the Boltzmann distribution in this case specifies both the distribution of velocities (the standard Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution) and also an exponential decrease in gas density (and pressure) with height. It is very unlikely for a molecule to be at a high altitude, just as it is very unlikely for a molecule to have a high velocity. The high energy associated with rare high velocities comes from occasional random collisions building up that high speed. Similarly the high energy associated with high altitude comes from random collisions occassionally pushing a molecule to great heights. These statistically rare occurences are both equally captured by the Boltzmann distribution. Note also that since the temperature is uniform in equilibrium, the distribution of velocities at any given altitude is that same Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at that temperature.

Force Balance

The decrease in pressure with height produces a pressure-gradient force that acts on “parcels of gas” in the same way that the gravitational force does, but in the opposite direction. At equilibrium or steady-state, when statistical properties of the gas cease changing, the two forces must balance.

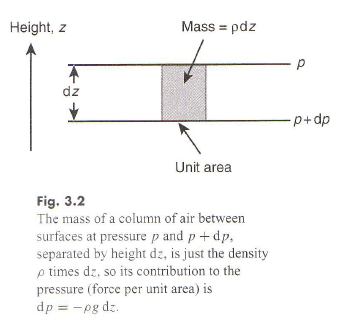

That leads to the equation of hydrostatic balance equating the pressure gradient force to the gravitational force:

dp/dz = – mng

(here p is pressure and n is the number density of molecules – N/V for N molecules in volume V). In equilibrium n(z) is given by the Boltzmann distribution:

n(z) = c.e(-mgz/kT);

for the ideal gas pressure is given by p = nkT, so the hydrostatic balance equation becomes:

dp/dz = k T dn/dz = k T c (-mg/kT) e(-g m z/kT) = – mg c e(-mgz/kT) = – m n(z) g

I.e. the Boltzmann distribution for this ideal gas system automatically ensures the system is in hydrostatic equilibrium.

Another approach to this sort of analysis is to look at the detailed flow of molecules near an imaginary boundary. This is done in textbook calculations of the thermal conductivity of an ideal gas, for example, where a gradient in temperature results in net flow of energy (necessarily from hotter to colder). In our system with gravitational force and pressure gradients both must be taken into account in such a calculation. Such calculations are somewhat complex and depend on assumptions about molecular size and neglecting other interactions that would make the gas non-ideal, but the net effect must always satisfy the same thermodynamic laws as every other such system: in thermodynamic equilibrium temperature is uniform and there is no net energy flow through any imagined boundary.

In conclusion, after sufficient time that statistical properties cease changing, all these examples of a system with a Venus-like atmosphere must reach essentially the same isothermal or near-isothermal state. The gravitational field and adiabatic lapse rate cannot explain the high surface temperature on Venus if incoming solar radiation does not reach (at least very close to) the surface.

_____________________________________________________________________

By Leonard Weinstein

Solar Heating and Outgoing Radiation Balances for Earth and Venus

The basic heating mechanism for any planetary atmosphere depends on the balance and distribution of absorbed solar energy and outgoing radiated thermal energy. For a planet like Earth, the presence of a large amount of surface water and a relatively optically transparent atmosphere to sunlight dominates where and how the input solar energy and outgoing thermal energy create the surface and atmospheric temperatures. The unequal energy flux for day and night, and for different latitudes, combined with the planet rotation result in wind and ocean currents that move the energy around.

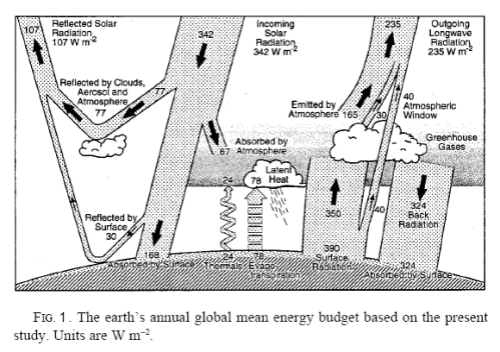

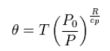

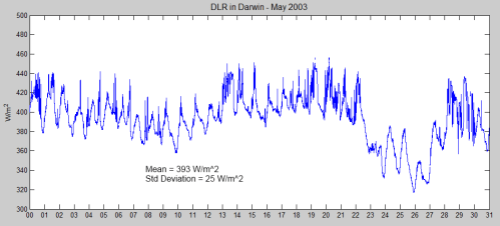

Earth is a much more complex system than Venus for these reasons, and also due to the biological processes and to changing albedo due to changes in clouds and surface ice. The average energy balance for the Earth was previously shown by Science of Doom, but is shown in Figure 1 below for quick reference:

The majority of solar energy absorbed by the Earth directly heats the land and water. Some water evaporation carries this energy to higher altitudes, and is released by phase change (condensation). This energy is carried up by atmospheric convection.

In addition, convective heat transfer from the ground and oceans transfers energy to the atmosphere. It is the basic atmospheric temperature differences from day and night and at different latitude that creates pressure differences that drive the wind patterns that eventually mix and transport the atmosphere, but the buoyancy of heated air from the higher temperature surface areas also aids in the vertical mixing.

This energy is carried by convection up into the higher levels of the atmosphere and eventually radiates to space. The combination of convection of water vapor and surface heated air upwards dominates the total transported energy from the ground level. In addition, some of the ground level thermal energy is radiated up, with a portion of the thermal radiation passing directly from the ground to space. Water vapor, CO2, clouds, aerosols, and other greenhouse gases also absorb some of this radiated energy, and slightly increase the lower atmosphere and ground temperatures with back radiation effectively adding to the initial radiation, resulting in a reduced net radiation flux. This results in a higher temperature atmosphere and ground than without these absorbing materials.

Venus, however, is dominated by direct absorption of solar energy into the atmosphere (including clouds) rather than by the surface, so has a significantly different path to heat the atmosphere and ground. Venus has a very dense atmosphere (about 93 times the mass as Earth’s atmosphere), which extends to about 90 km altitude before the tropopause is reached. This is much higher than the Earth’s atmosphere.

Very dense clouds, composed mostly of sulfuric acid, reach to about 75 km, and cover the planet. The clouds have virga beneath them due to the very high temperatures at lower elevations. The clouds and thick haze occupy over half of the main troposphere height, with a fairly clear layer starting below about 30 km altitude. Due to the very high density of the atmosphere, dust and other aerosol particles (from the surface winds and possibly from volcanoes) also persist in significant quantity.

The atmosphere is 96.5% CO2, and contains significant quantities of SO2 (150 ppm), and even some H2O (20 ppm), and CO (17 ppm). These, along with the sulfuric acid clouds, dust, and other aerosols, absorb most of the incoming sunlight that is not reflected away, and also absorb essentially all of the outgoing long wave radiation and relay it to the upper atmosphere and clouds to eventually dump it into space.

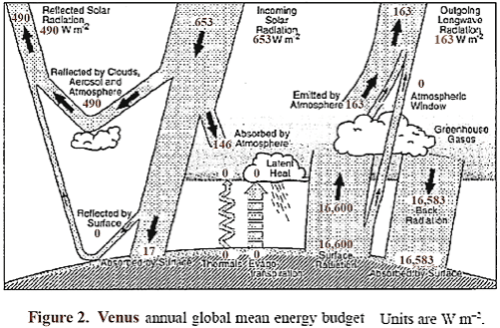

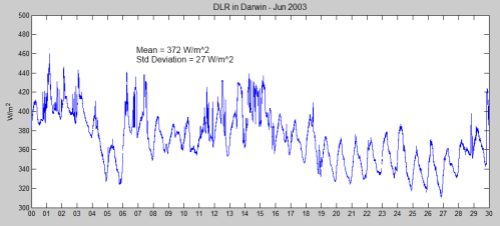

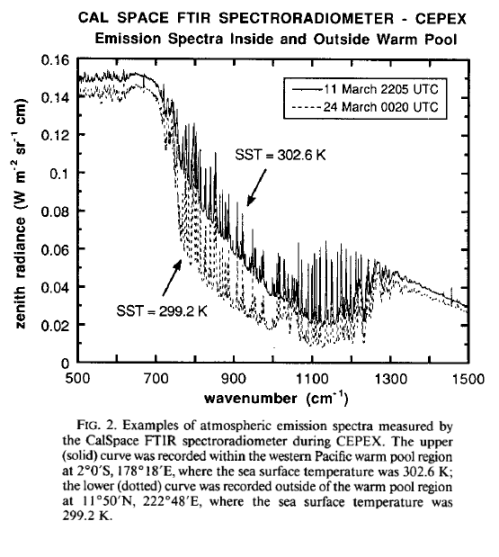

A sketch is shown in Figure 2, similar to the one used for Earth, which shows the approximate energy transfer in and out of the Venus atmosphere system. It is likely that almost all of the radiation out leaves from the top of the clouds and a short distance above, which therefore locks in the level of the atmospheric temperature at that location.

The surface radiation balance shown is my guess of a reasonable level. The top portion of the clouds reflects about 75% of incident sunlight, so that Venus absorbs an average of about 163 W/m², which is significantly less than the amount absorbed by Earth. About 50% of the available sunlight is absorbed in the upper cloud layer, and about 40% of the available sunlight is captured on the way down in the lower clouds, gases, and aerosols.

Thus an average of solar energy that reaches the surface is only about 17 W/m², and the amount absorbed is somewhat less, since some is reflected. The question naturally arises as to what is the source of wind, weather, and temperature distribution on Venus, and why is Venus so hot at lower altitudes.

Venus takes 243 days to rotate. However, continual high winds in the upper atmosphere takes only about 4 days to go completely around at the equator, so the day/night temperature variation is even less than it would have otherwise been. Other circulation cells for different latitudes (Hadley cells) and some unique polar collar circulation patterns complete the main convective wind patterns.

The solar energy absorbed by the surface is a far smaller factor than for Earth, and I am convinced it is not necessary for the basic atmospheric and ground temperature conditions on Venus. Since the effect on the atmospheres of planets from absorbed solar radiation is to locally change the atmospheric pressure that drive the winds (and ocean currents if applicable), these flow currents transport energy from one location and altitude to another. There is no specific reason the absorption and release of energy has to be from the ground to the atmosphere unless the vertical mixing from buoyancy is critical. I contend that direct absorption of solar energy into the atmosphere can accomplish the mixing, and this along with the fact that the top of the clouds and a short distance above is where the radiation leaves from, is in fact the cause of heating for Venus.

We observed that unlike Earth, which had about 72% of the absorbed solar energy heat the surface, Venus has 10% or less absorbed by the ground. Also the surface temperature of Venus (about 735 K) would result in a radiation level from the ground of about 16,600 W/m².

Since back radiation can’t exceed radiation up if the ground is as warm or warmer than the atmosphere above it, the only thing that can make the ground any warmer than the atmosphere above it is the ~17 W/m² (average) from solar radiation. The ground absorbed solar radiation plus absorbed back radiation has to equal the radiation out for constant temperature. If the absorbed solar radiation were all used to heat the ground, and the net radiation heat transfer was near zero (the most extreme case of greenhouse gas blocking possible), the average temperature of the ground would only be about 0.19 K warmer than the atmosphere above it, and the excess heat would need to be removed by surface convective driven heat transfer. The buoyancy would be extremely small, and contribute little to atmospheric mixing.

However, the net radiation heat transfer out of the ground is almost surely equal to or larger than the average solar heating at the ground, from some limited transmission windows in the gas, and through a small net radiation flux. The most likely effect is that the ground is equal to or a small amount cooler than the lower atmosphere, and there is probably no buoyancy driven mixing. This condition would actually require some convective driven heat transfer from the atmosphere to the ground to maintain the ground temperature. Since the measured lower atmosphere and ground temperature are on the dry adiabatic lapse rate curve projected down from the temperature at the top of the cloud layer, the net ground radiation flux is probably close to the value of 17 W/m². This indicates that direct solar heating of the ground is almost certainly not a source for producing the winds and temperature found on Venus. The question still remains: what does cause the winds and high temperatures found on Venus?

The main point I am trying to make in this discussion is that the introduction of solar energy into the relatively cool upper atmosphere of Venus, along with the high altitude location of outgoing radiation, are sufficient to heat the lower atmosphere and surface to a much higher temperature even if no solar energy directly reaches the surface. Two simplified models are discussed in the following sections to support the plausibility of that claim. This issue is important because it relates to the mechanism causing greenhouse gas atmospheric warming, and the effect of changing amounts of the greenhouse gases.

The Tall Room

The first model is an enclosed room on Venus that is 1 km x 1km x 100 km tall. This was selected to point out how adiabatic compression can cause a high temperature at the bottom of the room, with a far lower input temperature at the top. This is the type of effect that dominates the heating on Venus. While the first part of the discussion is centered on that room model, the analysis is also applicable for part the second model, which examines a special simplified approximation of the full dynamics on Venus.

The conditions for the tall room model are:

1) A gas is introduced at the top of a perfectly thermally insulated fully enclosed room 1 km x 1 km x 100 km tall, located on the surface of Venus. The walls (and bottom and top) are assumed to have negligible heat capacity. The walls and bottom and top are also assumed to be perfect mirrors, so they do not absorb or emit radiation.

2) The supply gas temperature is selected to be 250 K. The gas pours in to fill all of the volume of the room. Sufficient quantity of gas is introduced so that the final pressure at the top of the room is at 0.1 bar at the end of inflow. The entry hole is sealed immediately after introduction of the gas is complete.

3) The gas is a single atom molecule gas such as Argon, so that it does not absorb or emit thermal radiation. This made the problem radiation independent. I also put in a qualifier, to more nearly approximate the actual atmosphere, that the gas had a Cp like that of CO2 at the surface temperature of Venus [i.e., Cp=1.14 (kJ/kg K) for CO2 at 735 K]. Cp is also temperature independent.

The room height selected would actually result in a hotter ground level than the actual case of Venus. This was due to the choice of a room 100 km tall. The height to 0.1 bar for Venus is only about 65 km, which would give a better temperature match, but the difference is not important to the discussion. A dry adiabatic lapse rate forms as the gas is introduced due to the adiabatic compression of the gas at the lower level. The value of the lapse rate for the present example comes from a NASA derivation at the Planetary Atmospheres Data Node:

http://atmos.nmsu.edu/education_and_outreach/encyclopedia/adiabatic_lapse_rate.htm

The final result for the dry adiabatic lapse rate is:

Γp = -dT/dz|a = g/Cp (1)

In the room at Venus, this results in:

TH =Ttop +H * 8.9/1.14 (2)

Where H is distance down from the top.

Ttop remains at 250 K since it is not compressed (not because it was forced to be at that temperature by heat transfer), and Tbottom=1,031 K due to the adiabatic compression.

Two questions arise:

1) Is this dry adiabatic lapse rate what would actually develop initially after all the gas is introduced?

2) What would happen when the system comes to final equilibrium (however long it takes)?

The gas coming in would initially spread down to the bottom due to a combination of thermal motion and gravity, but the converted potential energy due to gravity over the room height would add considerable downward velocity, and this added downward velocity would convert to thermal velocity by collisions. Once enough gas filled the room to limit the MFP, added gas would tend to stay near the top until additional gas piled on top pushed it downwards, and this would increasingly compress the gas below from its added mass. The adiabatic compression of gas below the incoming gas at the top would heat the gas at the bottom to 1,031 K for the selected model. The top temperature would remain at 250 K, and the temperature profile would vary as shown by equation (2). Thus the answer to 1) is yes.

Strong convection currents may or may not be introduced in the room, depending on how fast the gas is introduced. To simplify the model, I assume the gas flows in slowly enough so that the currents are not important. It is quite clear that the temperature profile at the end of inflow would be the adiabatic lapse rate, with the top at 250 K and bottom at 1,031 K. If the final lapse rate went toward zero from thermal conduction, as Arthur postulated, even he admits it would take a very long time. The question now arises- what would cause heat conduction to occur in the presence of an adiabatic lapse rate? i.e., why would an initial adiabatic lapse rate tend to go toward an isothermal lapse rate if there is no radiation forcing (note: this lack of radiation forcing assumption is for the room model only). The cause proposed by Arthur and Science of Doom is based on their understanding of the Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics. They say that if there is a finite lapse rate (i.e., temperature gradient), there has to be conduction heat transfer. This arises from not considering the difference between temperature and heat. This is discussed in:

http://zonalandeducation.com/mstm/physics/mechanics/energy/heatAndTemperature/heatAndTemperature.html (difference between temperature and heat)

When we consider if there will be heat conduction in the atmosphere, we need to look at potential temperature rather than temperature. This is discussed at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Potential_temperature

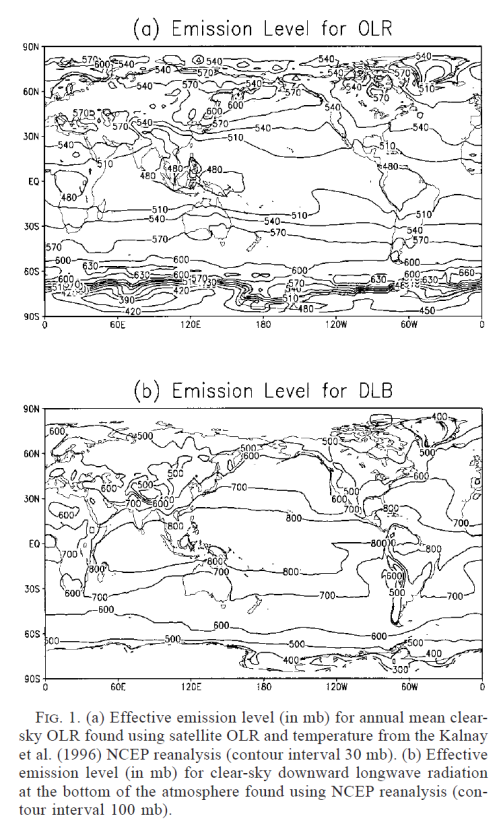

The potential temperature is shown to be:

This term in (3) is general, and thus valid for Venus, if the appropriate pressures are used.

A good discussion why the potential temperature is appropriate to use rather than the local temperature can be found at:

https://courseware.e-education.psu.edu/simsphere/workbook/ch05.html

This includes the following statements:

- “if we return to the classic conduction laws and our discussion of resistances, we note that heat should be conducted down a temperature gradient. Since we are talking about sensible heat, the appropriate gradient for the conduction of sensible heat is not the temperature but the potential temperature. The potential temperature is simply a temperature normalized for adiabatic compression or expansion”

- “When the environmental lapse rate is exactly dry adiabatic, there is zero variation of potential temperature with height and we say that the atmosphere is in neutral equilibrium. Under these conditions, a parcel of air forced upwards (downwards) will stay where it is once moved, and not tend to sink or rise after released because it will have cooled (warmed) at exactly the same rate as the environment”.

The above material supports the claim that there would be no movement from a dry adiabatic lapse rate toward an isothermal gas in the room model.

If the initial condition was imposed– that the lapse rate was below the dry adiabatic lapse rate, it is true that the gas would be very stable from convective mixing due to buoyancy, and the very slow thermal conduction, which would drive the temperature back toward the dry adiabatic lapse rate, could take a very long time (in the actual case, it would be much faster due to even small natural convection currents generally present). However, there is no reason for any lapse rate other than the dry adiabatic lapse rate to initially form, as the problem was posed, so that issue is not even relevant.

The final result of the room model is the fact that a very high ground temperature was produced from a relative cool supply gas due to adiabatic compression of the supply that was introduced at a high altitude. This is actually a consequence of gravitational potential energy being converted to kinetic energy. Once the dry adiabatic lapse rate formed, any small flow up or down stays in temperature equilibrium at all heights, so this is a totally stable situation, and would not tend toward an isothermal situation.

If there were present a sufficient quantity of gas in the present defined room that radiated and absorbed in the temperature range of the model, the temperature would tend toward isothermal, but that was not how the tall room example was defined.

Effect of an Optical Barrier to Sunlight reaching the Ground

The second model I discussed with Science of Doom, Arthur, and others, relates to my suggestion that if an optical barrier prevented any solar energy from transmitting to the ground, but that the energy was absorbed in and heated a thin layer just below the average location of effective outgoing radiation from Venus, in such a way that the heat was transmitted downward through the atmosphere, this could also result in the hot lower atmosphere and surface that is actually observed. The albedo, and the solar heating input due to day and night, and to different latitudes, was selected to match the actual values for Venus, and the radiation out was also selected to match the values for the actual planet.

This problem is much more complicated than the enclosed room case for two reasons.

The first is that it is a dynamic and non-uniform case. The second is due to the fact that the actual atmosphere is used, with radiation absorption and emission, and the presence of clouds. The lower atmosphere and surface of the planet Venus are much hotter than for the Earth, even though the planet does not absorb as much solar energy as the Earth. It is closer to the Sun than Earth, but has a much higher albedo due to a high dense cloud layer composed mostly of sulfuric acid drops. The discussion will not attempt to examine the historical circumstances that led up to the present conditions on Venus, but only look at the effect of the actual present conditions.

In order to examine this model, I had postulated that if all of the solar heating was absorbed near the top of Venus’s atmosphere, but with the day and night and latitude variation, the heat transfer to the atmosphere downward would eventually be mixed through the atmosphere and maintain the adiabatic lapse rate, with the upper atmosphere held to the same temperature as at the present. Since the atmosphere has gases, clouds, and aerosols that absorb and radiate most if not all of the thermal radiation, this is a different problem from the tall room.

However, it appears that the radiation flux levels are relatively small, especially at lower levels, so the issue hinges on the relative amount of forcing by convective flow compared to net radiation up (which does tend to reduce the lapse rate). I use the actual temperature profile as a starting point to see if the model is able to maintain the values. Different starting profiles would complicate the discussion, but if the selected initial profile can be maintained, it is likely all reasonable initial profiles would tend to the same long-term final levels.

The assumption that the solar heating and radiation out all occur in a layer at the top of the atmosphere eliminates positive buoyancy as a mechanism to initially couple the solar energy to the atmosphere. However, the direct thermal heat-transfer with different amounts of heating and cooling at different locations causes some local expansion and contraction of different locations of the top of the atmosphere, and this causes some pressure driven convection to form.

The pressure differences from expansion and contraction set a flow in motion that greatly increases surface heat transfer, and this flow would become turbulent at reasonable induced flow speeds. This increases heat transfer and mixing to larger depths. The portions cooler than the local average atmosphere will be denser than local adiabatic lapse rate values from the average atmosphere, and thus negative buoyancy would cause downward flow at these locations.

As the flow moved downward, it compressed but initially remains slightly cooler than the surrounding, with some mixing and diffusion spreading the cooling to ever-larger volumes. At some level, the flow down actually passes into a surrounding volume that is slightly cooler, rather than warmer, than the flow, due to the small but finite radiation flux removing energy from the surrounding. At this point the downward flow stream is warming the surrounding. The question arises: how much energy is carried by the convection, and could it easily replace radiated energy, so as to maintain a level near the dry adiabatic lapse rate?

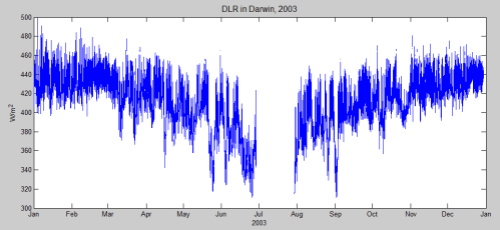

A few numbers need to be shown here to best get an order of magnitude of what is going on. Arthur has already made some of these calculations. The average input energy of 158 W/m² applied to Venus’s atmosphere would take about 100 years to change the average atmospheric temperature by 500 K. This means that to change it even 0.1 K (on average) would take about 7 days. Since the upper atmosphere at low latitudes only takes about 4 days to completely circulate around Venus, the temperature variations from average values would be fairly small if the entire atmosphere were mixed.

However, for the model proposed, only a very thin layer would be heated and cooled under the absorbing layer. Differences in net radiation flux would also help transfer energy up and down some. This relatively thin layer would thus have much higher temperature variation than the average atmosphere mass would (but still only a few degrees). The pressure variations due to the upper level temperature variations would cause some flow circulation and vertical mixing to occur throughout the atmosphere. The circulating flows may or may not carry enough energy to overcome radiation flux levels to maintain the dry adiabatic lapse rate. Let us look at the near surface flow, and a level of radiation flux of 17 W/m².

What excess temperature and vertical convection speed is needed to carry energy able to balance that flux level. Assume a temperature excess of only 0.026 K is carried and mixed by convection due to atmospheric circulation. Also assume the local horizontal flow rate near the ground is 1 m/s. If a vertical mixing of only 0.01 m/s were available, the heat added would be 17 W/m², and this would balance the lost energy due to radiation, thus allowing the dry adiabatic lapse rate to be maintained.

This shows how little convective circulation and mixing are needed to carry solar heated atmosphere from high altitudes to lower levels to replace energy lost by radiation flux levels in the atmosphere, and maintain a near dry adiabatic lapse rate. It is the solar radiation that is supplying the input energy, and adiabatic compression that is heating the atmosphere. As long as the lapse rate is held close to the adiabatic level with sufficient convective mixing, it is the temperature at the location in the atmosphere where the effective outgoing radiation is located that sets a temperature on the adiabatic lapse rate curve and adiabatic compression determines the lower atmosphere temperature.

Since the exact details of the heat exchanges are critical to the process, this optically sealed region near the top of the atmosphere is a poorly defined model as it stands, and the question of whether it actually would work as Arthur and Science of Doom question is not resolved, although an argument can be made that there are processes to do the mixing. However, the real atmosphere of Venus absorbs almost all of the solar energy in its upper half, and this much larger initial absorption volume does clearly do the job. I have shown the ground likely has little if any effect on the actual temperature on Venus.

Some Concluding Remarks

The initial cause for this discussion was the question of why the surface of Venus is as hot as it is. A write-up by Steve Goddard implied that the high pressure on Venus was a major factor, and even though some greenhouse gas was needed to trap thermal energy, it was the pressure that was the major contributor. The point was that an adiabatic lapse rate would be present with or without a greenhouse gas, and the major effect of the greenhouse gas was to move the location of outgoing radiation to a high altitude. The outgoing level set a temperature at that altitude, and the ground temperature was just the temperature at the outgoing radiation effective level plus the increase due to adiabatic compression to the ground. The altitude where the effective outgoing radiation occurs is a function of amount and type of greenhouse gases. Steve’s statement is almost valid. If he qualified it to state that enough greenhouse gas is still needed to limit the radiation flux, and keep the outgoing radiation altitude near the top of the atmosphere, he would have been correct. Thus both the amount of atmosphere (and thus pressure and thickness), and amount of greenhouse gases are factors. Any statement that greenhouse gases are not needed if the pressure is high enough is wrong (but this was not what Steve Goddard said).

Another issue that came up was the need for the solar energy to heat the ground in order for the hot surface of Venus to occur. I think I made reasonable arguments that this is not at all true. While there is a small amount of solar heating of the ground, the ground is probably actually slightly cooler that the atmosphere directly above it due to radiation, and so there is no buoyant mixing and no heating of the atmosphere from the ground other than the small radiated contribution. The main part of solar energy is absorbed directly into the atmosphere and clouds, and is almost certainly the driver for winds and mixing, and the high ground temperature.

The final issue is what would happen if most (say 90%) of the CO2 were replaced by say Argon in Venus’s atmosphere. Three things would happen:

1) The adiabatic lapse rate would greatly increase due to the much lower Cp of Argon.

2) The height of the outgoing radiation would probably decrease, but likely not much due to both the presence of the clouds, and the fact that the density is not linear with altitude, and matching a height with remaining high CO2 level would only drop 10 to 15 km out of the 75 to 80, where outgoing radiation is presently from. If in fact it is the clouds that cause most of the outgoing radiation, there may not be any drop in outgoing level.

3) The radiation flux through the atmosphere would increase, but probably not nearly enough to prevent the atmospheric mixing from maintaining an adiabatic lapse rate. Keep in mind that Venus has 230,000 times the CO2 as Earth. Even 10% of this is 23,000 times the Earth value.

The combination of these factors, especially 1), would probably result in an increase in the ground temperature on Venus.

Updated CO2 – An Insignificant Trace Gas – Part One

August 6, 2010 by scienceofdoom

Just a note that CO2 – An Insignificant Trace Gas? – Part One has been significantly rewritten.

There’s probably too not much of interest for regular readers, as I’ve taken material from more recent posts to replace the old.

And I didn’t try to cover the 500 different reasons why people think CO2 IS an insignificant trace gas..

Posted in Commentary | 1 Comment »