Recap

Part One of the series started with this statement:

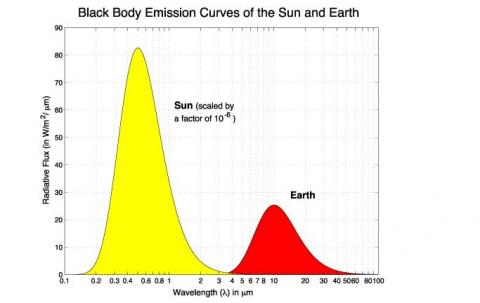

If there’s one area that often seems to catch the imagination of many who call themselves “climate skeptics”, it’s the idea that CO2 at its low levels of concentration in the atmosphere can’t possibly cause the changes in temperature that have already occurred – and that are projected to occur in the future. Instead, the sun, that big bright hot thing in the sky (unless you live in England), is identified as the most likely cause of temperature changes.

And covered the “zero-dimensional” model of the sun and the earth. Also known as the “billiard ball” model. It was just a starting point to understand the very basics.

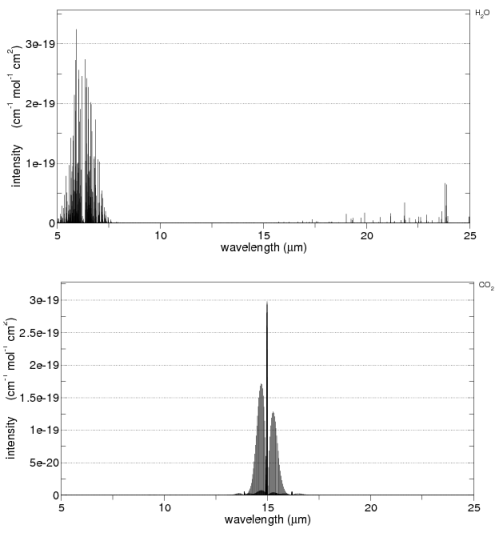

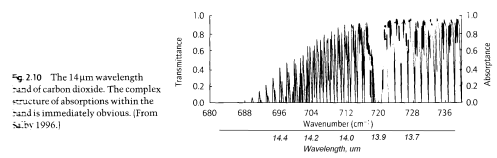

In Part Two we looked a little closer at why certain gases absorbed energy in certain bands and what the factors were that made them more, or less, effective “greenhouse” gases.

In this part, we are going to start looking at the “1-dimensional” model. I try and keep any maths as basic as possible and have separated out some maths for the keen students.

When you arrive at a new subject, the first time you see an analysis, or model, it can be confusing. After you’ve seen it and thought about it a few times it becomes more obvious and your acceptance of it grows – assuming it’s a good analysis.

So for people new to this, if at first it seems a bit daunting but you do want to understand it, don’t give up. Come back and take another look in a few days..

Models

If your background doesn’t include much science it’s worth understanding what a “model” is all about. Especially because many people have their doubts about GCM’s or “Global Climate Models”.

One of the ways that a model of a physics (or any science) problem is created is by starting from first principles, generating some equations and then finding out what the results of those equations are. Sometimes you can solve this set of equations “analytically” – which means the result is a formula that you can plot on a graph and analyze whichever way you like. Usually in the real world there isn’t an “analytical” solution to the problem and instead you have to resort to numerical analysis which means using some kind of computer package to calculate the answer.

The starting point of any real world problem is a basic model to get an understanding of the key “parameters” – or key “players” in the process. Then – whether you have an analytical solution or have to do a numerical analysis doesn’t really matter – you play around with the parameters and find out how the results change.

Additionally, you look at how closely the initial equations matched the actual situation you were modeling and that gives you an idea of whether the model will be a close fit or a very rudimentary one.

And you take some real-world measurements and see what kind of match you have.

Radiative Transfer

In the “zero dimensional” analysis we used a very important principle:

Energy into a system = Energy out of a system, unless the system is warming or cooling

The earth’s climate was considered like that for the simple model. And for the simple model we didn’t have to think about whether the earth was heating up, the actual temperature rise is so small year by year that it wouldn’t affect any of those results.

In looking at “radiative transfer” – or energy radiated through each layer of the atmosphere – this same important principle will be at the heart of it.

What we will do is break up the atmosphere into lots of very thin sections and analyze each section. The mathematical tools are there (calculus) to do that. The same kind of principles are applied, for example, when structural engineers work out forces in concrete beams – and in almost all physics and engineering problems.

And when we step back and try and re-analyze, again it will be on the basis of Energy in = Energy out

If you are new to ideas of radiation and absorption, go back and take a look at Part One – if you haven’t done so already.

In this first look I’ll keep the maths as light as possible and try and explain what it means. If following a little maths is what you want, there is some extra maths separated out.

First Step – Absorption

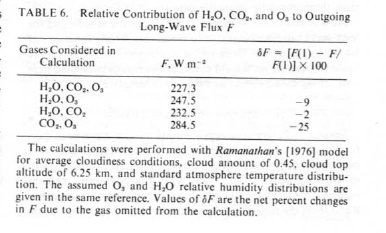

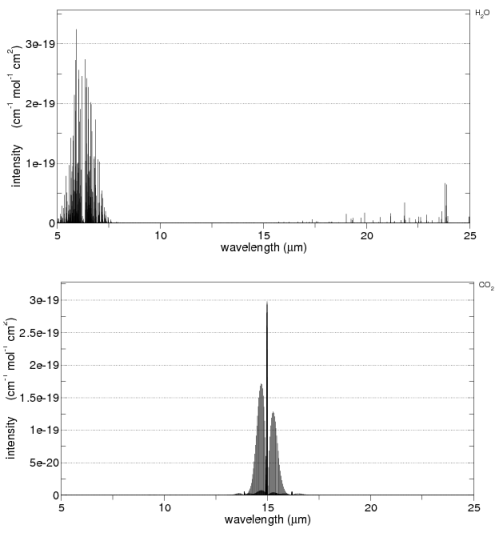

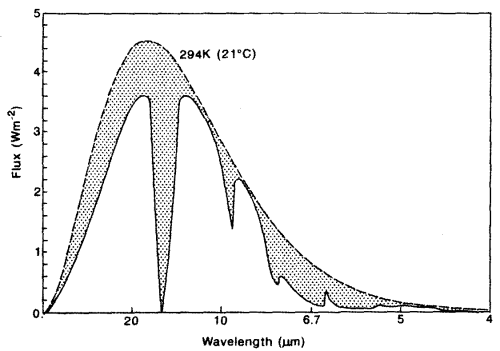

As we saw in part one, radiation absorbed by a gas is not constant across wavelengths. For example, here is CO2 and water vapor:

CO2 and water vapor absorption, by spectracalc.com from the HITRANS database

What we want to know is if we take radiation of a given wavelength which travels up through the atmosphere, how much of the radiation is absorbed?

We’ll define some parameters or “variables”.

I(λ) – The intensity, I, of radiation which is a function of wavelength, λ

I0(λ) – is the initial or starting condition (the intensity at the earth’s surface).

z – the vertical height through the atmosphere

n – how much of an absorbing gas is present

σ(λ) – absorption cross-section at wavelength λ (this parameter is dependent on the gas we are considering, and identifies how effective it is at capturing a photon of radiation at that wavelength)

The result of a simple mathematical analysis produces an equation that says that as you:

- increase the depth through the atmosphere that the radiation travels

- or the concentration of the gas

- or its “absorption cross-section”

Then more radiation is absorbed. Not too surprising!

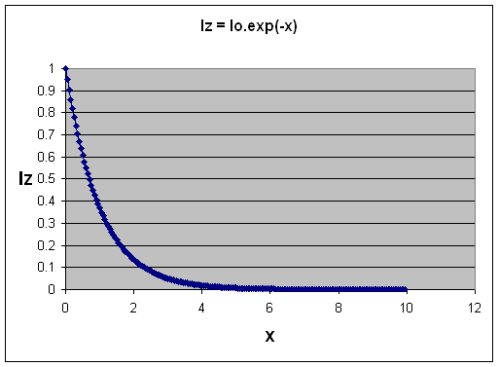

When the concentration of the gas is independent of depth (or height) the mathematical result becomes:

Iz = I0(λ).exp(-nσ(λ)z) also written as Iz = I0(λ).e-nσ(λ)z

This is the Beer-Lambert Law. The assumption that the number of gas molecules is independent of depth isn’t actually correct in the real world, but this first simple approximation gets us started. We could write n(z) in the equation above to show that n was a function of depth through the atmosphere.

[In the above equation, e is the natural log value of 2.781 that comes up everywhere in natural processes. To make complex equations easier to read, it is a convention to write “e to the power of x” as “exp(x)”]

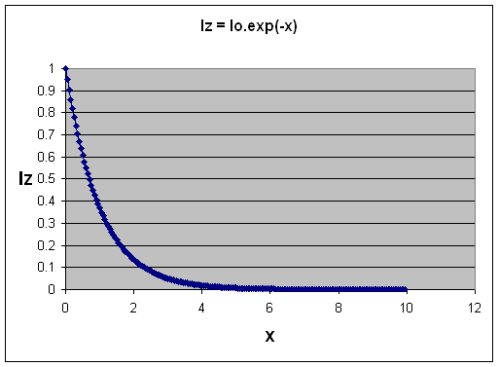

Here’s what the function looks like as “nσ(λ)z” increases – I called this term “x” here in this graph.

Transmittance of Radiation as "optical thickness" (x) increases.

It’s not too hard to imagine now. Iz is the amount of radiation making it through the gas. Iz=1 means all of it got through, and Iz=0 means none of it got through.

As you increase vertical height through the gas, or the amount of the gas, or the absorption of the gas, then the amount of radiation that gets through decreases. And it doesn’t decrease linearly. You see this kind of shape of curve everywhere in nature including the radiation decay of uranium..

This result is not too surprising to most people. But it’s knowing only this part which has many confused, because the question comes – about CO2 – doesn’t it saturate?

Isn’t it true that as CO2 increases eventually it has no effect? And haven’t we already reached that point?

Excellent questions. Skip the maths derivation of this section if you aren’t interested to find out about our Second Step – Radiation

First Step – Absorption – Skip this, it’s the Maths

You can skip this if you don’t like maths.

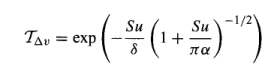

The intensity of light of wavelength λ is I(λ). This light passes through a depth dz (“thin slice”) of an absorber with number concentration n, and absorption cross-section σ(λ), and so is reduced by an amount dI(λ) given by:

dI(λ) = -I(λ)nσ(λ)dz = I(λ)dχ [equation 1]

where χ is defined as optical depth. It’s just a convenient new variable that encapsulates the complete effect of that depth of atmosphere at that wavelength for that gas.

We integrate equation 1 to obtain the intensity of light transmitted a distance z through the absorber Iz(λ):

Iz(λ) = I0(λ) exp{-∫nσ(λ)dz} [equation 2]

[note the integral is from 0 to z – not able to get the webpage to display what I want here]

In the case where the concentration of the absorbing gas is independent of the depth through the atmosphere the above equation is simplified to the Beer Lambert Law

Iz = I0(λ).exp(-nσ(λ)z) also written as Iz = I0(λ).e-nσ(λ)z

Note that this assumption is not strictly true of the atmosphere in general – the closer to the surface the higher the pressure and, therefore, there is more of absorbing gases like CO2.

Second Step – Radiation

Once the atmosphere is absorbing radiation something has to happen.

The conceptual mistake that most people make who haven’t really understood radiative transfer is they think of it something like torchlight trying to shine through sand – once you have enough sand nothing gets through and that’s it.

But energy absorbed has to go somewhere and and in this case the energy goes into increased heat of that section of the atmosphere, as we saw in Part Two of this series.

In general, and especially true in the troposphere (the lower part of the atmosphere up to around 10km), the increased energy of a molecule of CO2 (or water vapor, CH4, etc) heats up the molecules around it – and that section of the atmosphere then radiates out energy, both up and down.

Let’s introduce a new variable, B = intensity of emitted radiation

The relationship between I (radiation absorbed) – and B (radiation emitted) – integrated across all wavelengths, all directions and all surfaces is linked through conservation of energy.

But these two parameters are not otherwise related. Making it more difficult to conceptually understand the problem.

I depends on the radiation from the ground, which in turn is dependent on the energy received from the sun and longwave radiation re-emitted back to the ground.

Whereas B is a function of the temperature of that “slice” of the atmosphere.

The equation that includes absorption and emission for this thin “slice” through the atmosphere becomes:

dI = -Inσdz + Bnσdz = (I – B)dχ (where χ is defined as optical depth)

dI is “calculus” meaning the change in I, dz is the change in z and dχ is the change in χ, or optical thickness.

What does this mean? Well, if I could have just written down the “result” like I did in the section on absorption, I would have done, but because it has become more difficult, instead I have written down the equation linking B and I in the atmosphere..

What it does mean is that the more radiation that is absorbed in a given “slice” of the atmosphere, the more it heats up and consequently the more that “slice” then re-emits radiation across a spectrum of wavelengths.

Solving the Equation to Find out what’s Going on

There are two concepts introduced above:

- absorption, relatively easy to understand

- emission, a little harder but linked to absorption by the concept “energy in = energy out”

From here there are two main approaches..

- One approach is called the grey model of radiative transfer, and it uses a big simplification to show how radiation moves energy through the atmosphere.

- The other approach is to really solve the equations using numerical analysis via computers.

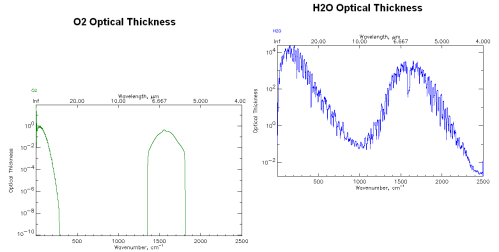

The problem is that we have some equations but they aren’t simple. We saw the Beer-Lambert law of absorption links to the emission in a given section of the atmosphere, but we know that the absorption is not constant across wavelengths.

So we have to integrate these equations across wavelengths and through the atmosphere (to link radiation flowing through each “slice” of the atmosphere)

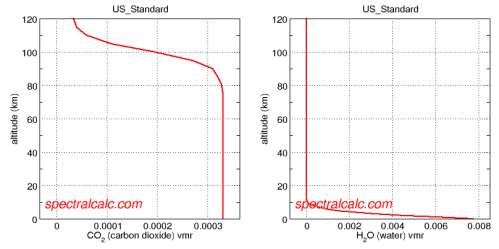

To really find the solutions – how much longwave radiation gets re-radiated back down to the earth’s surface as a result of CO2, water vapor and methane – we need a powerful computer with all of the detailed absorption bands of every gas, along with the profile of how much of each gas at each level in the atmosphere.

The good news is that they exist. But the bad news is that you can’t grab the equation and put it in excel and draw a graph – and find out the answer to that burning question that you had.. what about the role of CO2? and how does that compare with the role of water vapor?

And I still haven’t spelt out the saturation issue..

Finding out that the subject is more complex that it originally appeared is the first step to understanding this subject!

The important concept to grasp before we move on is that it is not just about absorption, it’s also about re-emission.

The Gray Model

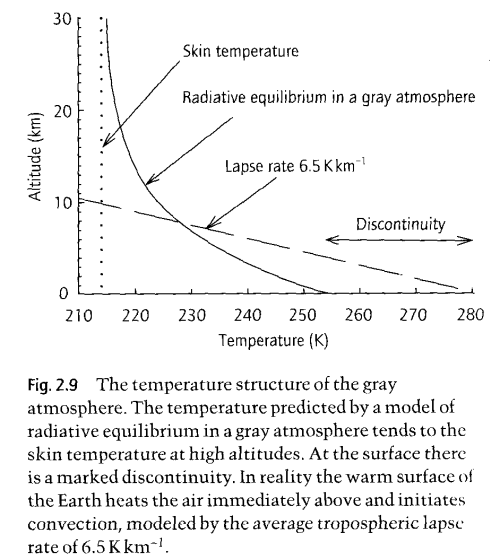

The “gray” model is very useful because it allows us to produce a simple mathematical model of the temperature profile through the atmosphere. We can do this because instead of thinking about the absorption bands, instead we assume that the absorption across wavelengths is constant.

What? But that’s not true!

Well, we do it to get a conceptual idea of how energy moves through the atmosphere when absorption and re-emission dominate the process. We obviously don’t expect to find out the exact effect of any given gas. The gray model uses the equations we have already derived and adds the fact that the absorber varies in concentration as a function of pressure.

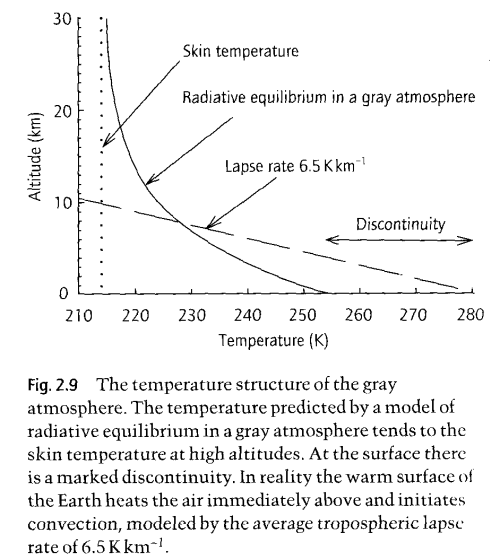

The Gray Model of Radiative Equilibrium, from "Handbook of Atmospheric Science" Hewitt and Jackson (2003)

The graph shown here is the result of developing the equations we have already seen, both for absorption and the link between absorption and re-emission.

The equations totally ignore convection! On the graph you can see the real “lapse rate”, which is the change in temperature with altitude. This is dominated by convection, not by radiation.

So how does the gray model help us?

It shows us how the temperature profile would look in an atmosphere with no convection and where there is significant and uniform absorption of longwave radiation.

Convection exists and is more significant than radiation in the troposphere – for moving energy around! Not for absorbing and re-emitting energy. The significance of the real “environmental lapse rate” of 6.5K/km is that it will change the re-emission profile. So it complicates the numerical analysis we need to do. It means that when the numerical analysis is done of the equations we have already derived, the real lapse rate is one more factor that has to be added to that 1-d analysis.

To get a conceptual feel for how that might change things – remember how the radiation spectrum changes with temperature – not a huge amount. So at each layer in the atmosphere the radiation spectrum using the real atmospheric temperature profile will be slightly different than using the “gray model”. But it can be taken into account.

Conclusion

This post has covered a lot of ground and not given you a nice tidy result. Sorry about that.

It’s an involved subject, and there’s no point jumping to the conclusion without explaining what the processes are. It is understanding the processes involved in radiative physics and the way in which the subject is approached that will help you understand the subject better.

And especially important, it will help you see the problems with a flawed approach. There are lots of these on the internet. There isn’t a nice tidy analytical expression which links radiative forcing to CO2 concentration, and which separates out CO2 from water vapor. But 1-d numerical models can generate reliable and believable results.

In Part Four, we will finally look at saturation, how it’s misunderstood, how much radiative forcing more CO2 will add (all other things being equal!) and how CO2 compares with water vapor.

So watch out for Part Four, and feel free to comment on this post or ask questions.

Update – Part Four is now online

The IPCC and the Credibility of Climate Science

January 26, 2010 by scienceofdoom

First, what recent events (Jan 2010)?

The issues arising from the story in the UK Mail that the IPCC used “sexed-up” climate forecasts to put political pressure on world leaders:

Then there are a number of stories on a similar theme where the predictions of climate change catastrophe weren’t based on “peer-reviewed” literature but on reports from activist organizations, like the WWF. And the reports were written not by specialists in the field, but activists..

And these follow the “climategate” leak of November 2009 where emails from the CRU from prominent IPCC scientists like Phil Jones, Michael Mann, Keith Briffa and others show them in a poor light.

This blog is focused on the science but once you read stories like this you wonder how much of anything to believe.

If you are in one of those mindsets, this blog is probably the wrong place to come.

Be Skeptical

Being skeptical doesn’t mean not believing anything you hear. Being skeptical means asking for some evidence.

I see many individuals watching the recent events unfolding and saying:

Actually the two aren’t related. CO2 and the IPCC are not an indivisible unit!

It’s a challenge to keep a level head. To be a good skeptic means to realize that an organization can be flawed, corrupt even, but it doesn’t mean that all the people whose work it has drawn on have produced junk science.

When a government tries to convince its electorate that it has produced amazing economic results by stretching or inventing a few statistics, does this mean the statisticians working for that government are all corrupt, or even that the very science of statistics is clearly in error?

Most people wouldn’t come to that conclusion.

Politics and Science

But in climate science it’s that much harder because to understand the science itself takes some effort. The IPCC is a political body formed to get political momentum behind action to “prevent climate change”. Whereas climate science is mostly about physics and chemistry.

They are a long way apart.

For myself, I believe that the IPCC has been bringing the science of climate into disrepute for a long time, despite producing some excellent work. It has claimed too much certainty about what the science can predict. Tenuous findings that might possibly show that a warmer world will lead to more problems are pressed into service. Findings against are ignored.

This causes a problem for anyone trying to find out the truth.

It’s tempting to dismiss anything that is in an IPCC report because of these obvious flaws – and they have been obvious for a long time. But even that would be a mistake. Much of what the IPCC produces is of a very high quality. They have a bias, so don’t take it all on faith..

The Easy Answer

Find a group of people you like and just believe them.

The Road Less Travelled

My own suggestion, for what it’s worth, is to put time into trying to get a better understanding of climate science. Then it is that much easier to separate fact from fiction. One idea – if you live near a university, you can visit their library and probably find a decent entry-level book or two about climate science basics.

Another idea – for around $40 you can purchase Elementary Climate Physics by Prof. F.W. Taylor – from http://www.bookdepository.co.uk/ – free shipping around the world. Amazing. And I don’t get paid for this advert either, not until I work out how to get adverts down the side of the blog. It’s an excellent book with some maths, but skip the maths and you will still learn 10x more than reading any blog including mine.

And, of course, visit blogs which focus on the science and ask a few questions.

Be prepared to change your mind.

Posted in Climate Models, Commentary | 4 Comments »