Introduction

This is the long-promised eighth part of the seven-part series on CO2 basics. Part One introduced the idea of CO2 with some basic concepts. Part Three opened up the radiative transfer equations, not solvable on the pocket calculator. Part Five showed two important solutions. And Part Seven showed the current best solutions along with what “radiative forcing” actually means, and where the IPCC logarithmic formula comes from.

The even numbers in the series shouldn’t be ignored either, especially Part Four which explained band models vs line by line (LBL) calculations.

Now the concept of “saturation” is one that everyone wants an answer to. Saturation, however, means different things to different people. Consider shining a torch through sand. Once you have a few millimeters thickness of sand, no light gets through. So adding a meter of sand won’t make any difference. That’s how most people are thinking about saturation and that is the perspective that we will look at in this article:

- For CO2 – will doubling CO2 (from pre-industrial) levels add any more warming?

- And will doubling it again add any more?

The answer already noted in earlier parts of this series is “yes”, but of course, everyone wants to know why, or what this means for the idea of “saturation”.

Boringly, we will first look at some results from the radiative transfer equations.

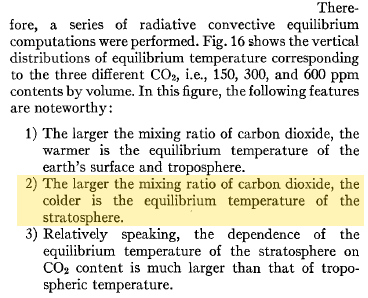

The RTE

The RTE were introduced in Part Three – these are the full solution to the problem of absorption and emission by each “layer” of the atmosphere. The equations are challenging to solve because every absorption line for each gas has to be calculated, and a similar process goes on for emission of radiation by each layer in the atmosphere. It’s not some kind of mystery, it’s just very computationally expensive, so big computers and plenty of time are required. See Part Six for an example of theory matched up with measurement.

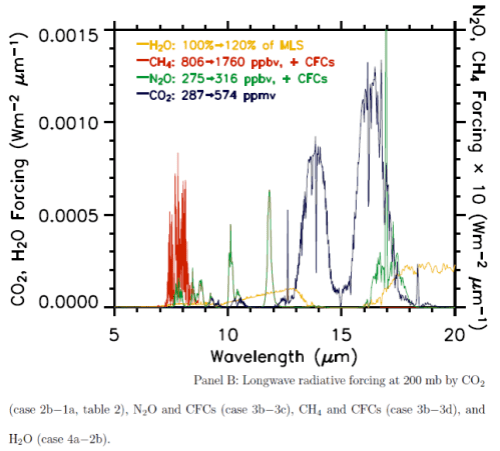

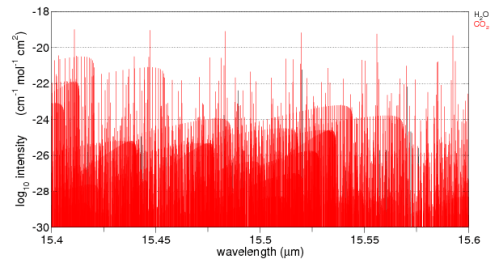

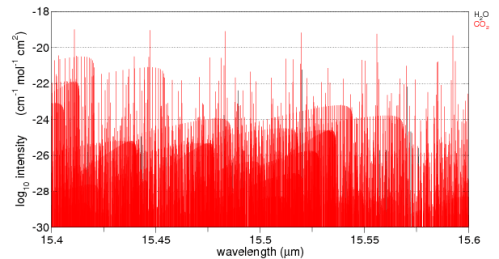

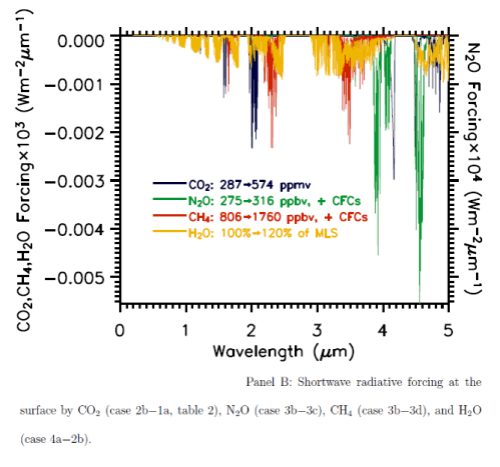

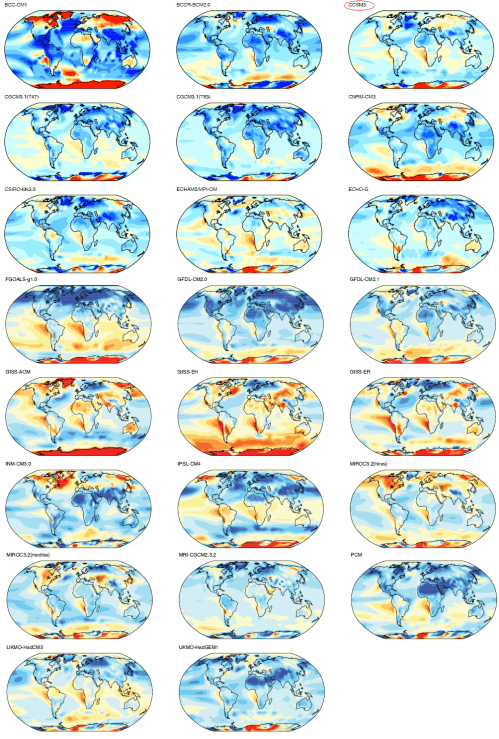

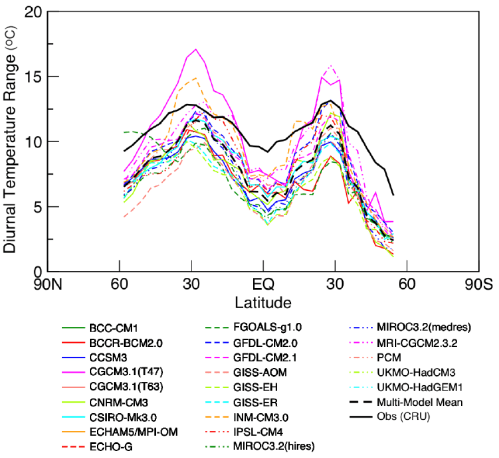

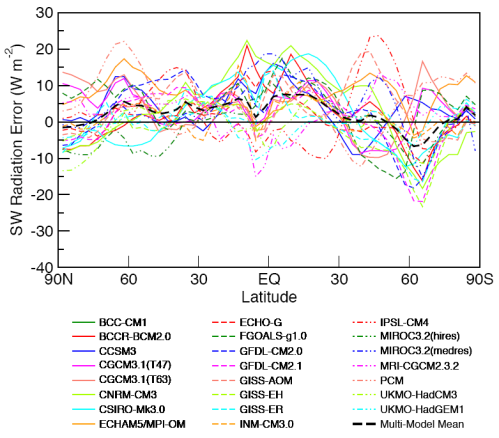

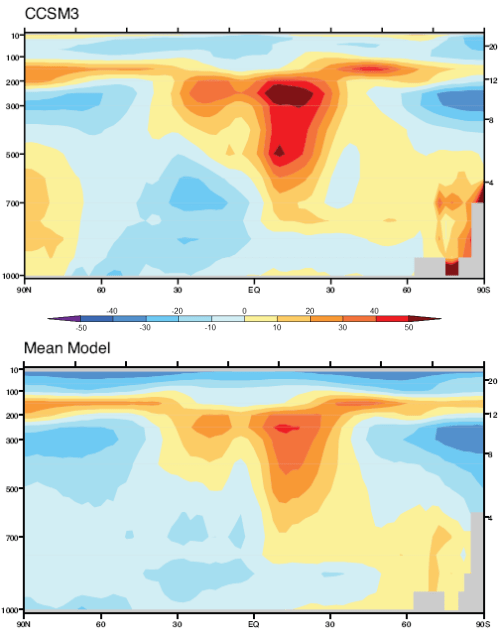

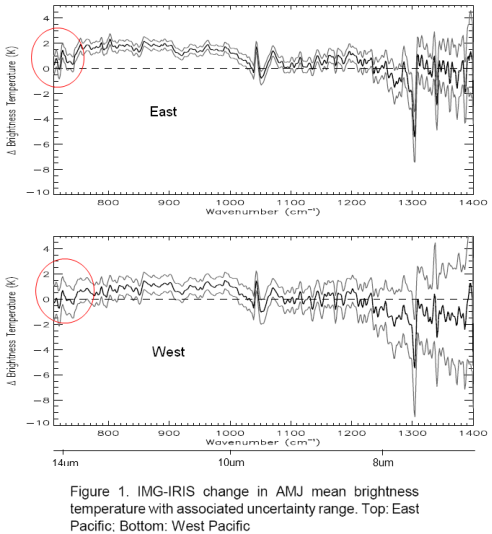

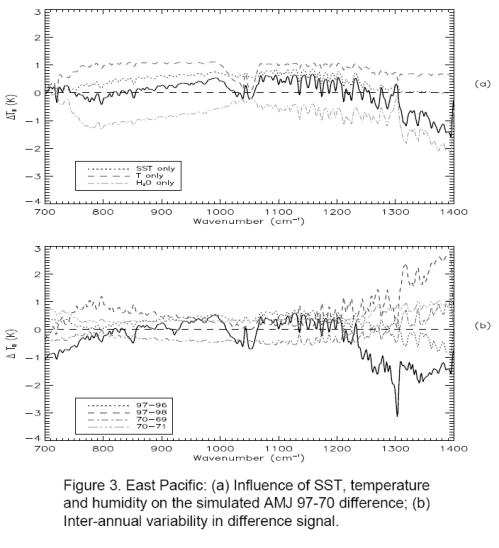

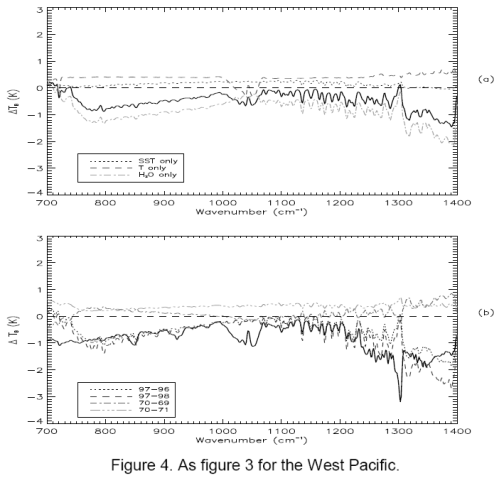

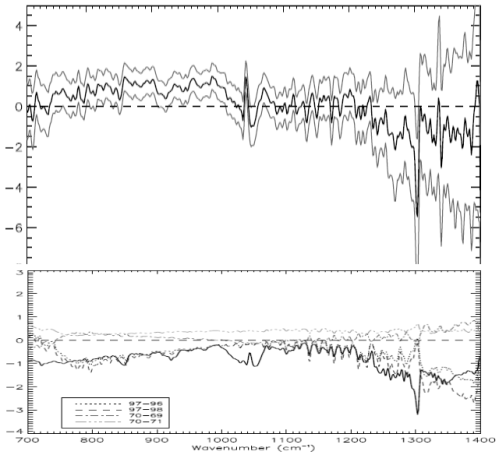

A fairly recent model inter-comparison effort was done which included the results from LBL (line by line spectra) for increases in CO2 and other trace gases. The inter-comparison focused on comparing the results from many GCM’s with the LBL results (see note 1). Although it wasn’t the focus of the paper, a graph of radiative forcing vs wavelength was included:

This is from W.D. Collins (2006), reference below. (Interested students will note that the vertical axis appears to have the wrong units, I have emailed Prof Collins to ask about this – update, he has confirmed that the vertical axis is incorrect).

The blue line is the “radiative forcing” vs wavelength for CO2.

The best way to explain why something called radiative forcing is used is that is a “standardization tool”. A simple explanation of radiative forcing is that it is the extra downward radiation at the tropopause before feedbacks from the surface and the lower atmosphere (the troposphere). You can see a little more on this concept in Part Seven.

Now that’s over with – check out the graph. Red is a methane increase from pre-industrial levels to current levels, green is a nitrous oxide increase and yellow is the effect of a possible increase in water vapor. The important point is that for the increases for CO2 (blue), most of the increase in energy is not in the center of the 15μm CO2 band.

It is interesting to see that the effect of the center of the CO2 band is not zero, although it is very low, but the main increase is in “the wings” of the band. This is the primary reason why doubling CO2 provides a significant increase in “radiative forcing” – or more heat into the surface and lower atmosphere.

To demonstrate this result wrong simply requires the interested student to prove the RTE (radiative transfer equations) wrong, or the line by line database of absorption for CO2 wrong, or the particular methods of solving the RTE in these models wrong. So it could all be over here.. but of course there’s more to think about.

By the way, the line by line method uses each individual absorption line stored in a huge database (like HITRANS), but the story is yet more complicated because each line has a definite width and a line shape, and these factors depend on the pressure and temperature. For example, each CO2 line is broader closer to the surface than it is high up in the troposphere. And the shape also changes. More on this at some later date, maybe..

Some Conceptual Ideas – Absorption and Re-emission and Planck Blackbody Radiation

Everyone likes to understand a subject conceptually. This is sometimes difficult but these mental models are very helpful if they can provide us with understanding. However, it is important to remember that just because something seems “conceptually right” doesn’t mean it is, and vice-versa. In the end, a theory stands or falls on the ability to falsify it and not on our ability to “picture it”. (The popularity of a theory on the other hand..)

The most important conceptual idea to understand is that the radiation from the surface which is absorbed by CO2 doesn’t just disappear. (The same applies to all “greenhouse” gases but I’ll stay with using CO2 as the prime example).

We will consider the atmosphere in a number of vertical “layers”, stacked one on top of the other. CO2 absorbs energy, shares it with other molecules in the atmosphere and therefore that layer of the atmosphere heats up (see note 2). Some molecules, like nitrogen and oxygen, have no ability to absorb or emit longwave radiation (see CO2 – Part Two), but by collision with molecules like CO2 and water vapor they will share energy and be at the same temperature.

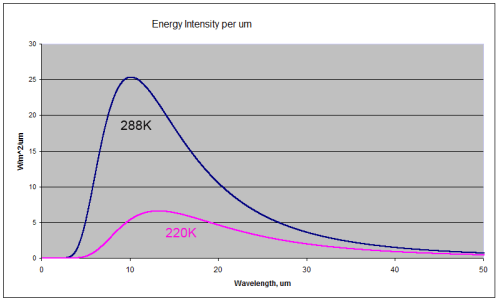

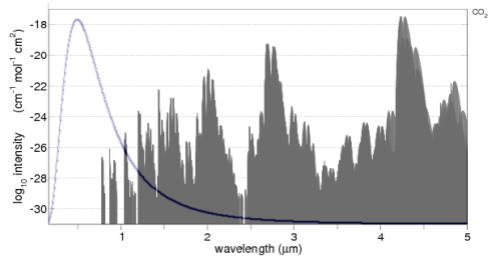

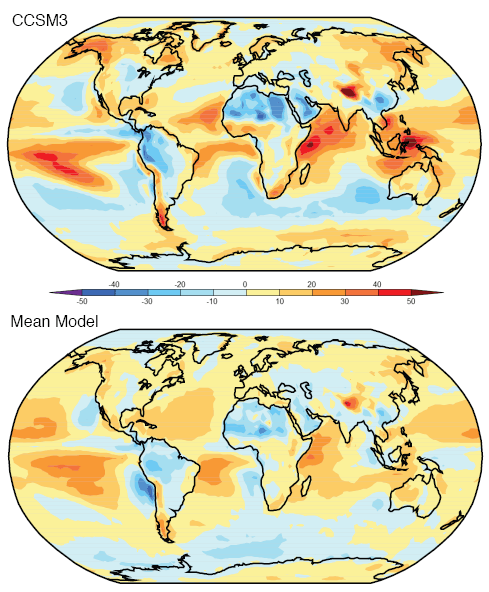

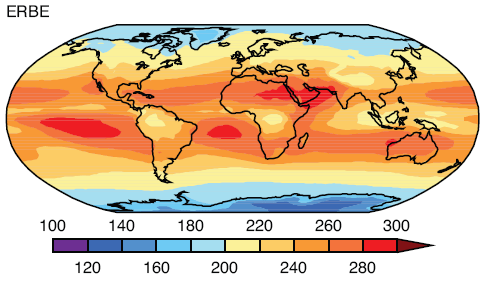

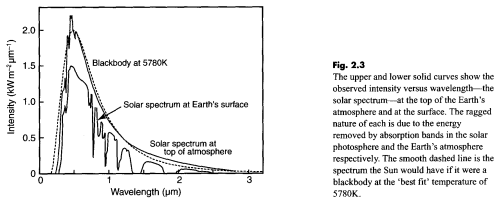

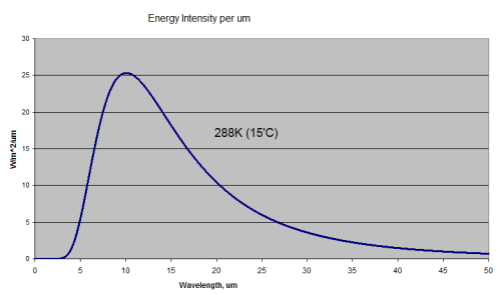

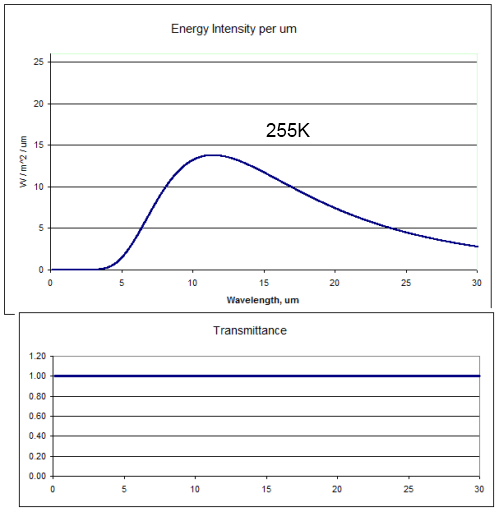

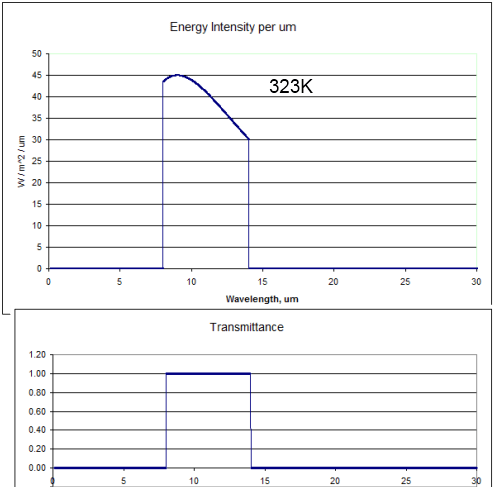

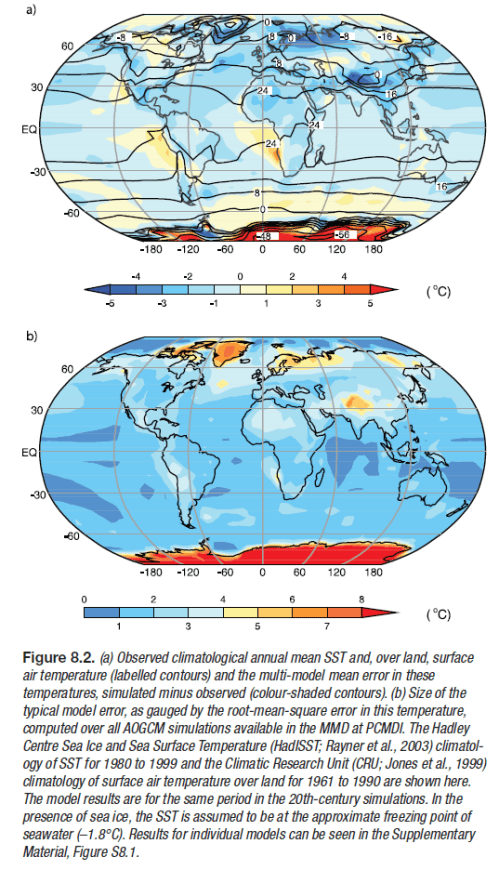

For those new to the basics of radiation, here are two comparison radiation curves for a blackbody at the typical temperature of the earth’s surface (288K or 15ºC) and at a typical temperature at the top of the troposphere

(220K or -53ºC).

You can see that the radiation emitted by a 288K body is a lot higher than the 220K body (the total integrated across all wavelengths is greater by a factor of 3). You can also see that for the colder body the energy has shifted to longer wavelengths (the wavelength of maximum radiance has moved from 10.1μm for 288K to 13.2μm for 220K).

A blackbody is a perfect radiator and absorber – so think of these curves as the ideal – the best that might be attained.

The surface of the earth is very close to a blackbody (the emissivity is close to 1) for longwave radiation – see The Dull Case of Emissivity and Average Temperatures. The atmosphere is not even close to being a blackbody. Atmospheric gases absorb and emit radiation at well-defined spectral lines. But the Planck function – as the curves above are called – tells us the “shape” that these spectral lines fit under.

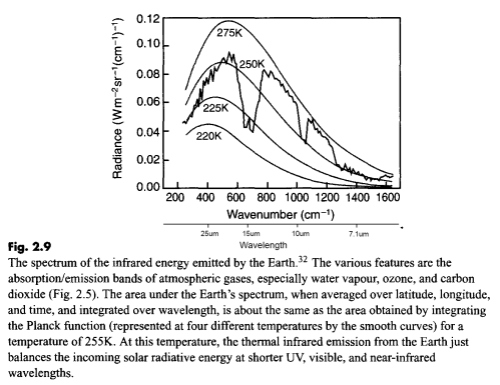

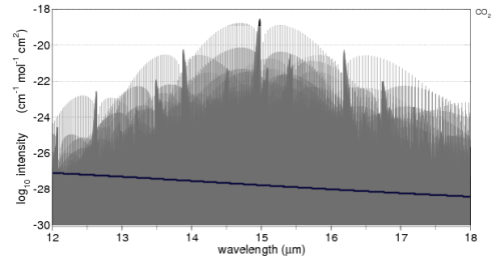

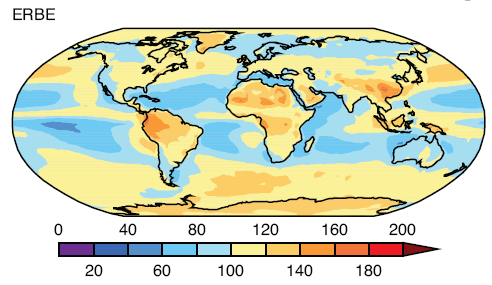

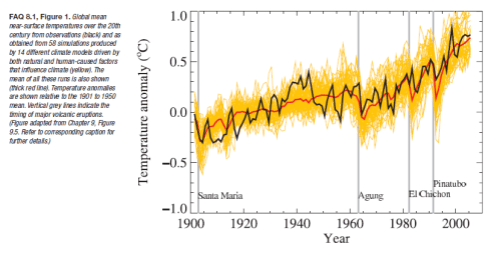

Here is a measurement of outgoing longwave radiation by satellite (the “upward” radiation) with the Planck function for different temperatures overlaid:

I’ve added “wavelength” under “wavenumber” on the horizontal axis for convenience.

What this shows is the effective temperature of radiation for each part of the longwave spectrum. Take a look at the spectrum between 10-13μm. The radiation between these wavelengths corresponds to around 270K. Now look at the spectrum between 14-16μm. The radiation here corresponds to around 223K.

That’s because there is not much absorption by the atmosphere in the 10-13μm spectrum, consequently most of the radiation from the surface goes straight out to space.

By comparison, absorption is very high between 14-16μm so almost no radiation from the surface goes straight out to space.

But – and here is the conceptual idea I want to get across – why is there any radiation between 14-16μm (measured by satellite)? Absorption by CO2 in the center of the 15um band is so strong that surely there should be no radiation – or nothing measurable..

This subject was covered in some detail in The Earth’s Energy Budget – Part Three, but essentially each layer of the atmosphere also radiates energy. If CO2 can absorb radiation at 15μm, it can also radiate at 15um. But it radiates according to its temperature. So when you see the measurement by satellite of the 15μm band reflecting a temperature of 223K you know that the bulk of the radiation was emitted by CO2 at a temperature of 223K (-50ºC).

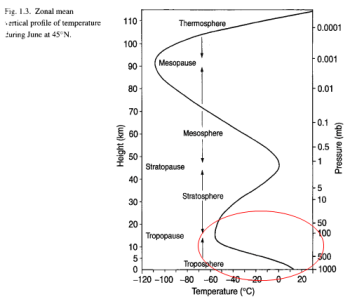

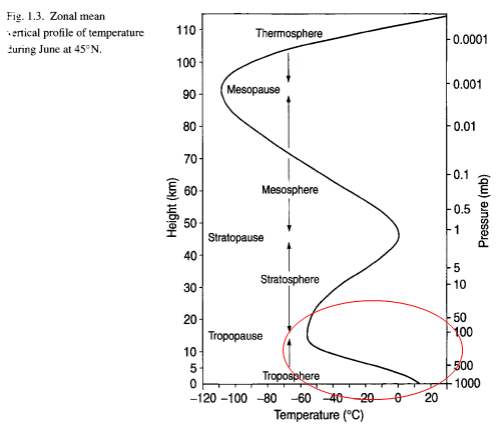

For the temperature of CO2 to be 223K (-50ºC) means that it must be located around the top of the troposphere:

How does all of this relate to “saturation”?

One Conceptual Saturation Idea – it Can’t Get any Colder

One way of thinking about the absorption and re-emission of 15μm radiation is like this – if the 15μm band is already radiating from the coldest part of the atmosphere, then increasing CO2 will have no effect on the earth’s energy balance because even if the 15μm band radiates from higher up, it won’t get any colder and, therefore, the amount of radiation at this wavelength won’t be decreased.

But this is just in the center of the 15μm band. As we saw from the detailed line by line calculation in the paper by Collins, the bulk of the reduction in outgoing radiation is from 13-14.5μm and from 15.5-17μm.

You can play around with these ideas by using the Modtran model. It uses band models (not line by line calculations) but band models give reasonable results. What is interesting is to increase the amount of CO2 and (looking down from 70km) see what effect takes place at 15μm – not much in the center of the band – for the reasons already explained: the atmosphere doesn’t get any colder.

However, you will notice that the width of this heavily saturated band increases – as with the more accurate treatment by Collins at the beginning of the article.

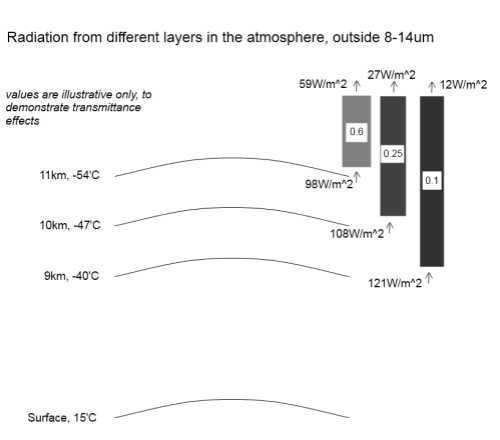

Another Conceptual Saturation Idea – the Two Slab Model

There is a simple model which is worth looking at by Barton Paul Levenson. What it demonstrates is that if you take a gas which absorbs across all longwave (>4μm) wavelengths, then even if this gas totally absorbs all radiation in the lower part of the atmosphere, adding more of this gas will still increase the surface temperature.

This is for the simple reason that the incoming solar energy at the top of the atmosphere must be balanced by energy leaving from the top of the atmosphere – otherwise temperature will increase (see The Earth’s Energy Budget – Part Two). And if one “layer” of the atmosphere totally absorbs it will still radiate energy to the atmosphere above. As the atmosphere gets thinner it will eventually be radiating out to space – and it’s at these levels (heights) in the atmosphere that adding more CO2 will reduce the outgoing radiation.

And if the outgoing radiation is reduced then there will be more incoming solar radiation than outgoing longwave radiation and the surface/atmosphere will heat up. Take a look at his model.

Fascinating as it is, I don’t think it answers the question of “saturation” or not by CO2 in the actual climate.

The reasons are complex, but read on if you are interested..

This is because the center of the CO2 band (15μm) is already radiating from the coldest part of the atmosphere. Therefore, increasing CO2 can’t reduce the radiation from the 15um band – unless more CO2 can change the temperature structure by lifting the height of the tropopause which will result in a colder tropopause.

In a climate with a “gray” absorber (one that absorbs equally across all wavelengths) an increase in this absorber would almost certainly change the tropopause height. Why? The tropopause is the point at which the atmosphere becomes optically thin and so radiation to space can take place from that point. Radiation is now more effective than convection at moving heat upwards through the atmosphere. So a climate model (even a more refined one with many layers) with a gray absorber will do as Levenson’s model predicts.

But a climate model with an almost transparent atmosphere in places will respond in less clear ways. Modeling the height and temperature of the tropopause is a difficult challenge and not something to get into here.

For those new to this topic, it probably doesn’t make a lot of sense. Think of this section as a “by the way an interesting idea about saturation..”

Conclusion

Most of the confusion about “saturation” of CO2 comes from a lack of understanding of how both absorption and re-emission are linked in the atmosphere.

The confusion also arises because atmospheric physics uses the term “saturation” to mean something more technically defined – that the atmosphere is “optically thick” at that wavelength. Two groups of people using the same word with a different (but related) meaning inevitably leads to confusion.

The radiative transfer equations are the basic and proven equations for the absorption and radiation of energy in the atmosphere. Solving these equations using line by line calculations shows that most of the additional effect from more CO2 occurs in the “wings” of the band and not in the band center.

Doubling CO2 from pre-industrial levels will lead to an increased “radiative forcing” of around 3.7 W/m2, and this part of climate science at least, is well understood.

Demonstrating that this result is wrong requires over-turning the radiative-convective model which currently calculates outgoing longwave radiation (at top of atmosphere) and downward longwave radiation (at the surface) quite accurately compared with measurements.

The mental models that many people have about saturation are not necessarily what is actually happening in the atmosphere.

Notes

Note 1 – The specific conditions for this inter-comparison (by Collins et al) were slightly different from the standardized method of “radiative forcing” in that they didn’t include stratospheric adjustment – allowing the stratospheric temperatures to achieve equilibrium after the changes in trace gases. This has a small but significant effect on the overall total values of radiative forcing, but the results are useful because the graph of radiative forcing against wavelength is given, whereas most results are simply given as a W/m2 value.

Note 2 – The subject of molecules of CO2 and water vapor absorbing energy and sharing this energy by collision with other molecules close by was covered to a limited extent in How Much Work Can One Molecule Do?

References

Radiative forcing by well-mixed greenhouse gases: Estimates from climate models in the IPCC AR4, W.D. Collins et al, Journal of Geophysical Research (2006)

Elementary Climate Physics, F.W. Taylor (2005) Oxford University Press