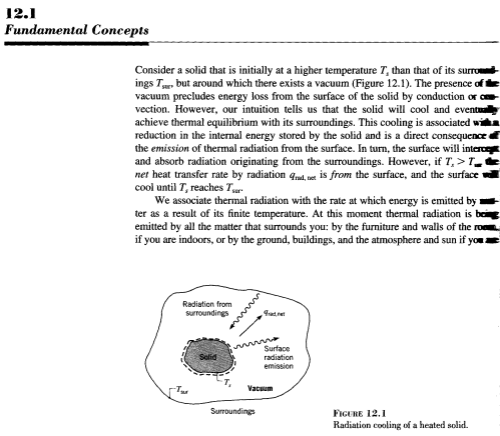

This could have been included in the Earth’s Energy Budget series, but it deserved a post of its own.

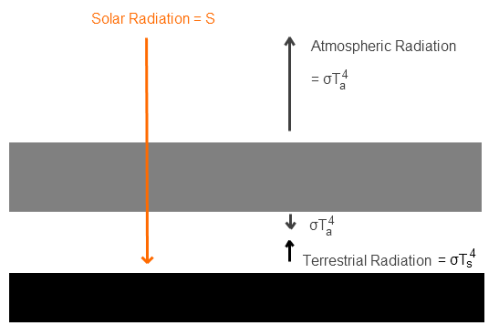

First of all, what is “back-radiation” ? It’s the radiation emitted by the atmosphere which is incident on the earth’s surface. It is also more correctly known as downward longwave radiation – or DLR

What’s amazing about back-radiation is how many different ways people arrive at the conclusion it doesn’t exist or doesn’t have any effect on the temperature at the earth’s surface.

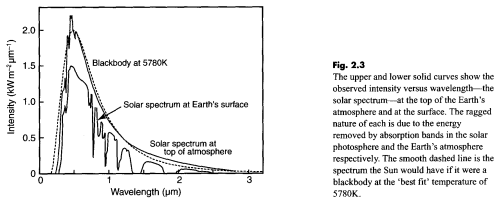

If you want to look at the top of the atmosphere (often abbreviated as “TOA”) the measurements are there in abundance. This is because (since the late 1970’s) satellites have been making continual daily measurements of incoming solar, reflected solar, and outgoing longwave.

However, if you want to look at the surface, the values are much “thinner on the ground” because satellites can’t measure these values (see note 1). There are lots of thermometers around the world taking hourly and daily measurements of temperature but instruments to measure radiation accurately are much more expensive. So this parameter has the least number of measurements.

This doesn’t mean that the fact of “back-radiation” is in any doubt, there are just less measurement locations.

For example, if you asked for data on the salinity of the ocean 20km north of Tangiers on 4th July 2004 you might not be able to get the data. But no one doubts that salt was present in the ocean on that day, and probably in the region of 25-35 parts per thousand. That’s because every time you measure the salinity of the ocean you get similar values. But it is always possible that 20km off the coast of Tangiers, every Wednesday after 4pm, that all the salt goes missing for half an hour.. it’s just very unlikely.

What DLR Measurements Exist?

Hundreds, or maybe even thousands, of researchers over the decades have taken measurements of DLR (along with other values) for various projects and written up the results in papers. You can see an example from a text book in Sensible Heat, Latent Heat and Radiation.

What about more consistent onging measurements?

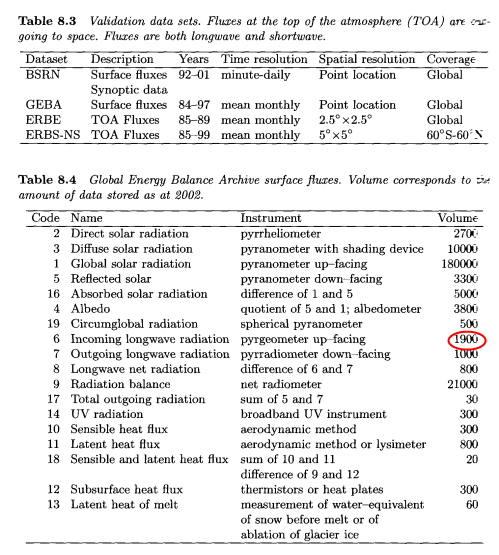

The Global Energy Balance Archive contains quality-checked monthly means of surface energy fluxes. The data has been extracted from many sources including periodicals, data reports and unpublished manuscripts. The second table below shows the total amount of data stored for different types of measurements:

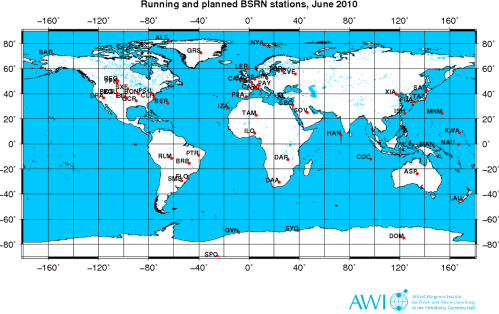

You can see that DLR measurements in the GEBA archive are vastly outnumbered by incoming solar radiation measurements. The BSRN (baseline surface radiation network) was established by the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP) as part of GEWEX (Global Energy and Water Cycle Experiment) in the early 1990’s:

The data are of primary importance in supporting the validation and confirmation of satellite and computer model estimates of these quantities. At a small number of stations (currently about 40) in contrasting climatic zones, covering a latitude range from 80°N to 90°S (see station maps ), solar and atmospheric radiation is measured with instruments of the highest available accuracy and with high time resolution (1 to 3 minutes).

Twenty of these stations (according to Vardavas & Taylor) include measurements of downwards longwave radiation (DLR) at the surface. BSRN stations have to follow specific observational and calibration procedures, resulting in standardized data of very high accuracy:

- Direct SW – accuracy 1% (2 W/m2)

- Diffuse radiation – 4% (5 W/m2)

- Downward longwave radiation, DLR – 5% (10 W/m2)

- Upward longwave radiation – 5% (10 W/m2)

Radiosonde data exists for 16 of the stations (radiosondes measure the temperature and humidity profile up through the atmosphere).

Click for a larger image

A slightly earlier list of stations from 2007:

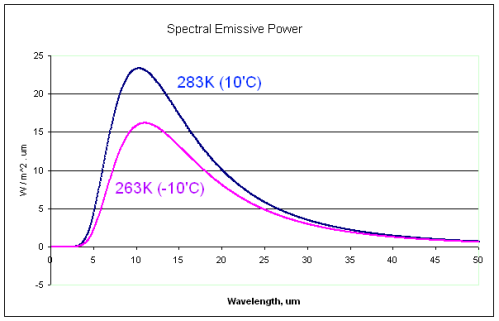

Solar Radiation and Atmospheric Radiation

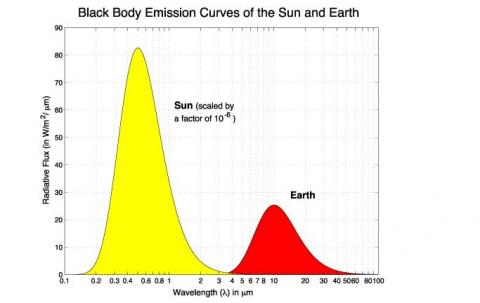

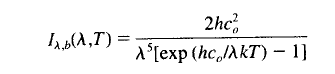

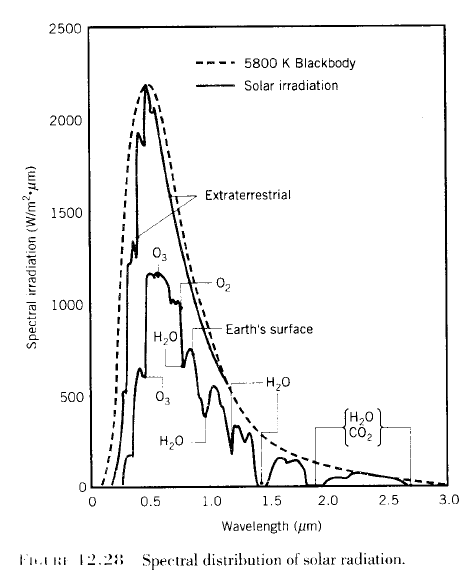

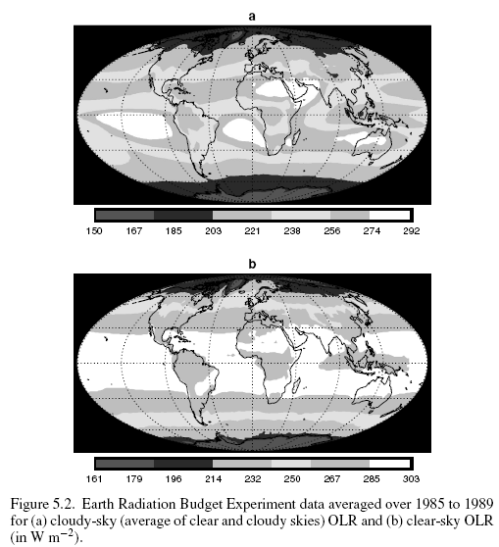

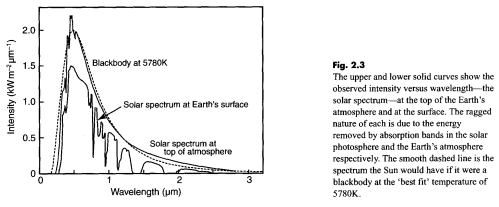

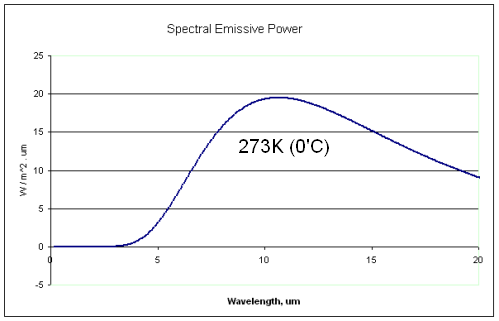

Regular readers of this blog will be clear about the difference between solar and “terrestrial” radiation. Solar radiation has its peak value around 0.5μm, while radiation from the surface of the earth or from the atmosphere has its peak value around 10μm and there is very little crossover. For more details on this basic topic, see The Sun and Max Planck Agree

.

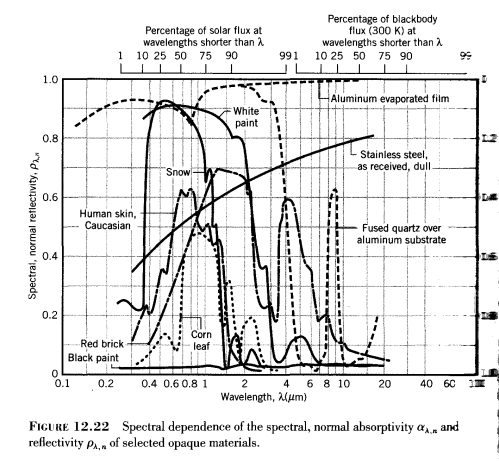

What this means is that solar radiation and terrestrial/atmospheric radiation can be easily distinguished. Conventionally, climate science uses “shortwave” to refer to solar radiation – for radiation with a wavelength of less than 4μm – and “longwave” to refer to terrestrial or atmospheric radiation – for wavelengths of greater than 4μm.

This is very handy. We can measure radiation in the wavelengths > 4μm even during the day and know that the source of this radiation is the surface (if we are measuring upward radiation from the surface) or the atmosphere (if we are measuring downward radiation at the surface). Of course, if we measure radiation at night then there’s no possibility of confusion anyway.

Papers

Here are a few extracts from papers with some sample data.

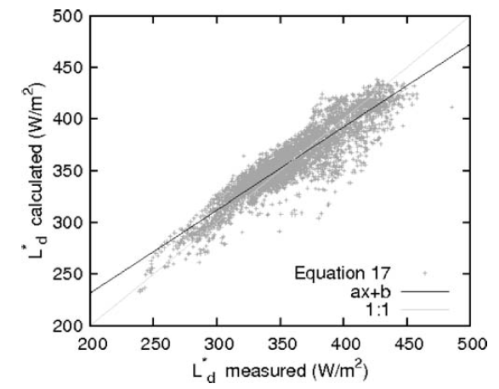

Downward longwave radiation estimates for clear and all-sky conditions in the Sertãozinho region of São Paulo, Brazil by Kruk et al (2010):

Atmospheric longwave radiation is the surface radiation budget component most rarely available in climatological stations due to the cost of the longwave measuring instruments, the pyrgeometers, compared with the cost of pyranometers, which measure the shortwave radiation. Consequently, the estimate of longwave radiation for no-pyrgeometer places is often done through the most easily measured atmospheric variables, such as air temperature and air moisture. Several parameterization schemes have been developed to estimate downward longwave radiation for clear-sky and cloudy conditions, but none has been adopted for generalized use.

Their paper isn’t about establishing whether or not atmospheric radiation exists. No one in the field doubts it, any more than anyone doubts the existence of ocean salinity. This paper is about establishing a better model for calculating DLR – as expensive instruments are not going to cover the globe any time soon. However, their results are useful to see.

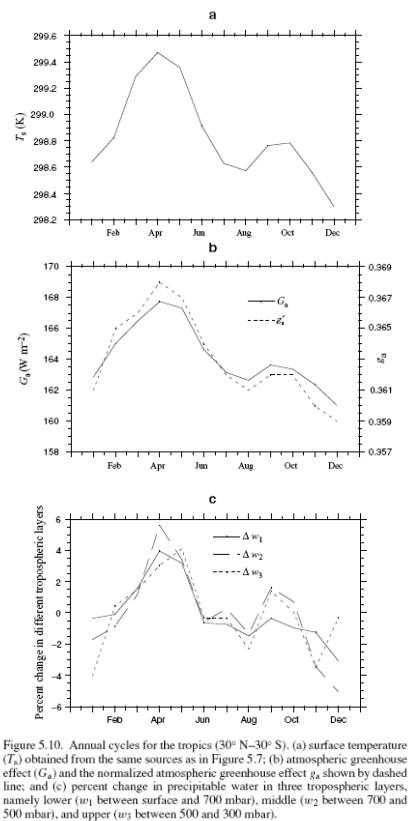

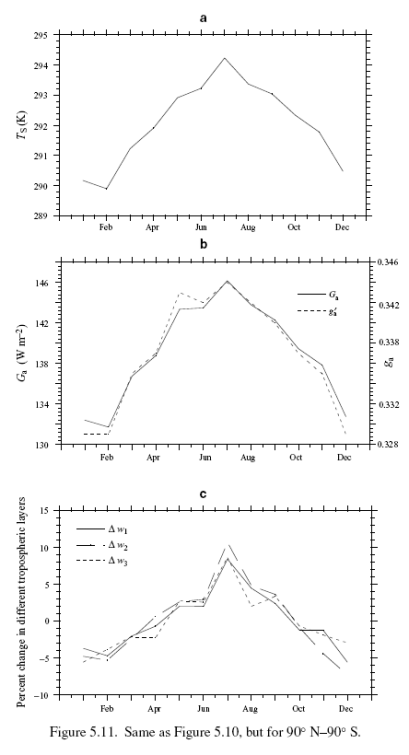

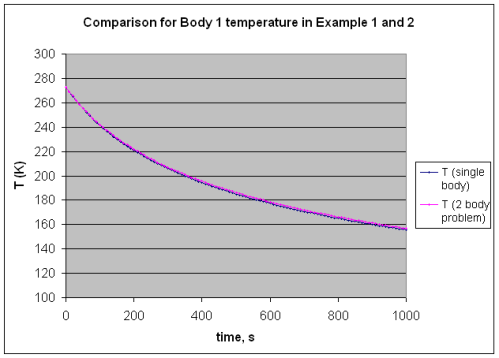

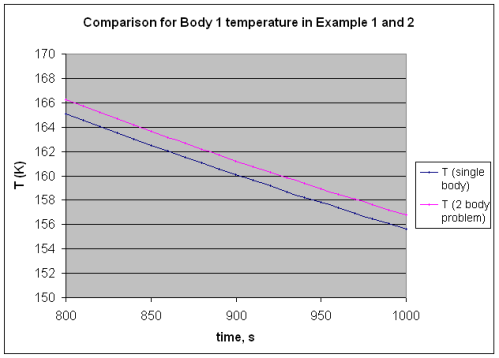

In another paper, Wild and co-workers (2001) calculated some long term measurements from GEBA:

This paper also wasn’t about verifying the existence of “back-radiation” – it was assessing the ability of GCMs to correctly calculate it. So you can note the long term average values of DLR for some European stations and one Japanese station. The authors also showed the average value across the stations under consideration:

And station by station month by month (the solid lines are the measurements):

Click on the image for a larger view

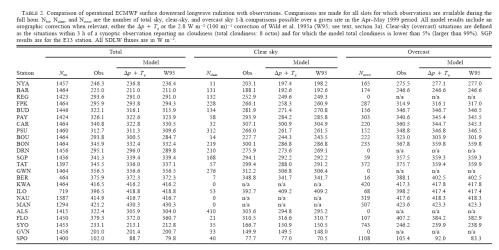

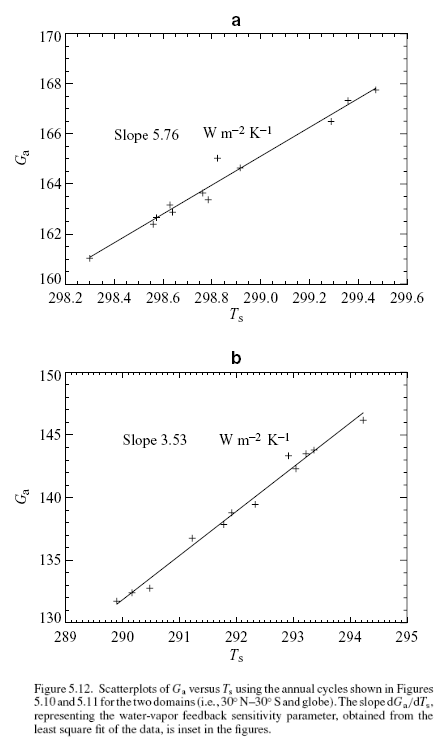

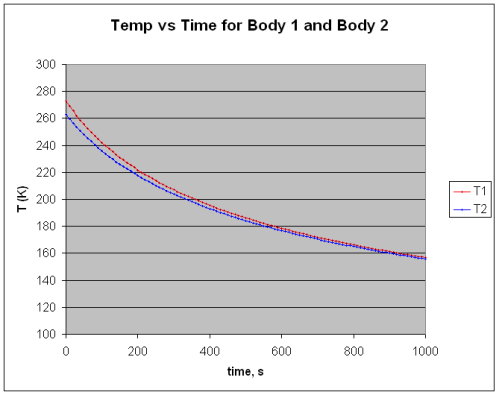

In another paper, Morcrette (2002) produced a comparison of observed and modeled values of DLR for April-May 1999 in 24 stations (the columns headed Obs are the measured values):

Click for a larger view

Once again, the paper wasn’t about the existence of DLR, but about the comparison between observed and modeled data. Here’s the station list with the key:

BSRN data

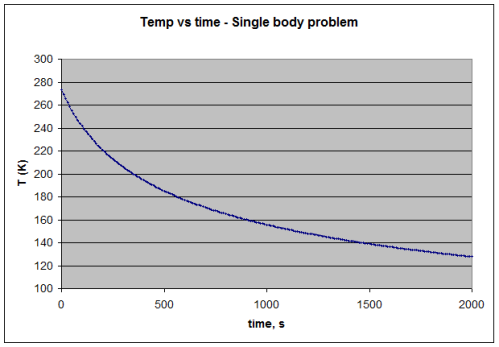

Here is a 2-week extract of DLR for Billings, Oklahoma from the BSRN archives. This is BSRN station no. 28, Latitude: 36.605000, Longitude: -97.516000, Elevation: 317.0 m, Surface type: grass; Topography type: flat, rural.

And 3 days shown in more detail:

Note that the time is UTC so “midday” in local time will be around 19:00 (someone good at converting time zones in October can tell me exactly).

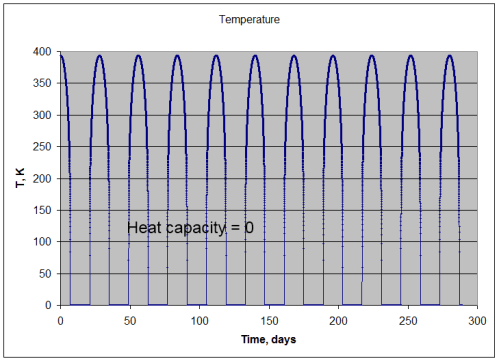

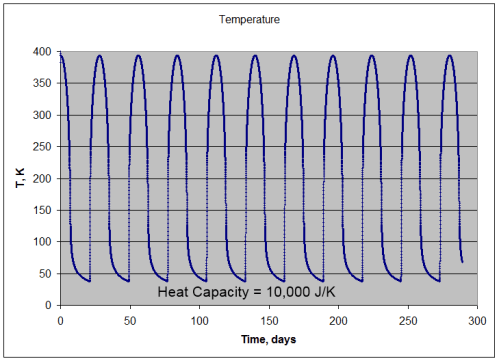

Notice that DLR does not drop significantly overnight. This is because of the heat capacity of the atmosphere – it cools down, but not as quickly as the ground.

DLR is a function of the temperature of the atmosphere and of the concentration of gases which absorb and emit radiation – like water vapor, CO2, NO2 and so on.

We will look at this some more in a followup article, along with the many questions – and questionable ideas – that people have about “back-radiation”.

Update: The Amazing Case of “Back-Radiation” – Part Two

The Amazing Case of “Back Radiation” – Part Three

Darwinian Selection – “Back Radiation”

Notes

Note 1 – Satellites can measure some things about the surface. Upward radiation from the surface is mostly absorbed by the atmosphere, but the “atmospheric window” (8-12μm) is “quite transparent” and so satellite measurements can be used to calculate surface temperature – using standard radiation transfer equations for the atmosphere. However, satellites cannot measure the downward radiation at the surface.

References

Radiation and Climate, I.M. Vardavas & F.W. Taylor, International Series of Monographs on Physics – 138 by Oxford Science Publications (2007)

Downward longwave radiation estimates for clear and all-sky conditions in the Sertãozinho region of São Paulo, Brazil, Kruk et al, Theoretical Applied Climatology (2010)

Evaluation of Downward Longwave Radiation in General Circulation Models, Wild et al, Journal of Climate (2001)

The Surface Downward Longwave Radiation in the ECMWF Forecast System, Morcrette, Journal of Climate (2002)