During a discussion following one of the six articles on Ferenc Miskolczi someone pointed to an article in E&E (Energy & Environment). I took a look and had a few questions.

The article is question is The Thermodynamic Relationship Between Surface Temperature And Water Vapor Concentration In The Troposphere, by William C. Gilbert from 2010. I’ll call this WG2010. I encourage everyone to read the whole paper for themselves.

Actually this E&E edition is a potential collector’s item because they announce it as: Special Issue – Paradigms in Climate Research.

The author comments in the abstract:

The key to the physics discussed in this paper is the understanding of the relationship between water vapor condensation and the resulting PV work energy distribution under the influence of a gravitational field.

Which sort of implies that no one studying atmospheric physics has considered the influence of gravitational fields, or at least the author has something new to offer which hasn’t previously been understood.

Physics

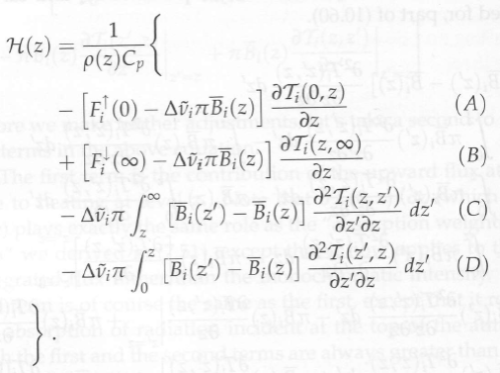

Note that I have added a WG prefix to the equation numbers from the paper, for ease of referencing:

First let’s start with the basic process equation for the first law of thermodynamics

(Note that all units of measure for energy in this discussion assume intensive properties, i.e., per unit mass):

dU = dQ – PdV ….[WG1]

where dU is the change in total internal energy of the system, dQ is the change in thermal energy of the system and PdV is work done to or by the system on the surroundings.

This is (almost) fine. The author later mixes up Q and U. dQ is the heat added to the system. dU is change in internal energy which includes the thermal energy.

But equation (1) applies to a system that is not influenced by external fields. Since the atmosphere is under the influence of a gravitational field the first law equation must be modified to account for the potential energy portion of internal energy that is due to position:

dU = dQ + gdz – PdV ….[WG2]

where g is the acceleration of gravity (9.8 m/s²) and z is the mass particle vertical elevation relative to the earth’s surface.

[Emphasis added. Also I changed “h” into “z” in the quotes from the paper to make the equations easier to follow later].

This equation is incorrect, which will be demonstrated later.

The thermal energy component of the system (dQ) can be broken down into two distinct parts: 1) the molecular thermal energy due to its kinetic/rotational/ vibrational internal energies (CvdT) and 2) the intermolecular thermal energy resulting from the phase change (condensation/evaporation) of water vapor (Ldq). Thus the first law can be rewritten as:

dU = CvdT + Ldq + gdz – PdV ….[WG3]

where Cv is the specific heat capacity at constant volume, L is the latent heat of condensation/evaporation of water (2257 J/g) and q is the mass of water vapor available to undergo the phase change.

Ouch. dQ is heat added to the system, and it is dU which is the internal energy which should be broken down into changes in thermal energy (temperature) and changes in latent heat. This is demonstrated later.

Later, the author states:

This ratio of thermal energy released versus PV work energy created is the crux of the physics behind the troposphere humidity trend profile versus surface temperature. But what is it that controls this energy ratio? It turns out that the same factor that controls the pressure profile in the troposphere also controls the tropospheric temperature profile and the PV/thermal energy ratio profile. That factor is gravity. If you take equation (3) and modify it to remove the latent heat term, and assume for an adiabatic, ideal gas system CpT = CvT + PV, you can easily derive what is known in the various meteorological texts as the “dry adiabatic lapse rate”:

dT/dz = –g/Cp = 9.8 K/km ….[WG5]

[Emphasis added]

Unfortunately, with his starting equations you can’t derive this result.

What I am talking about?

The Equations Required to Derive the Lapse Rate

Most textbooks on atmospheric physics include some derivation of the lapse rate. We consider a parcel of air of one mole. (Some terms are defined slightly differently to WG2010 – note 1).

There are 5 basic equations:

The hydrostatic equilibrium equation:

dp/dz = -ρg ….[1]

where p = pressure, z = height, ρ = density and g = acceleration due to gravity (=9.8 m/s²)

The ideal gas law:

pV = RT ….[2]

where V = volume, R = the gas constant, T = temperature in K, and this form of the equation is for 1 mole of gas

The equation for density:

ρ = M/V ….[3]

where M = mass of one mole

The First Law of Thermodynamics:

dU = dQ + dW ….[4]

where dU = change in internal energy, dQ = heat added to the system, dW = work added to the system

..rewritten for dry atmospheres as:

dQ = CvdT + pdV ….[4a]

where Cv = heat capacity at constant volume (for one mole), dV = change in volume

And the (less well-known) equation which links heat capacity at constant volume with heat capacity at constant pressure (derived from statistical thermodynamics and experimentally verifiable):

Cp = Cv + R ….[5]

where Cp = heat capacity (for one mole) at constant pressure

With an adiabatic process no heat is transferred between the parcel and its surroundings. This is a reasonable assumption with typical atmospheric movements. As a result, we set dQ = 0 in equation 4 & 4a.

Using these 5 equations we can solve to find the dry adiabatic lapse rate (DALR):

dT/dz = -g/cp ….[6]

where dT/dz = the change in temperature with height (the lapse rate), g = acceleration due to gravity, and cp = specific heat capacity (per unit mass) at constant pressure

dT/dz ≈ -9.8 K/km

Knowing that many readers are not comfortable with maths I show the derivation in The Maths Section at the end.

And also for those not so familiar with maths & calculus, the “d” in front of a term means “change in”. So, for example, “dT/dz” reads as: “the change in temperature as z changes”.

Fundamental “New Paradigm” Problems

There are two basic problems with his fundamental equations:

- he confuses internal energy and heat added to get a sign error

- he adds a term for gravitational potential energy when it is already implicitly included via the pressure change with height

A sign error might seem unimportant but given the claims later in the paper (with no explanation of how these claims were calculated) it is quite possible that the wrong equation was used to make these calculations.

These problems will now be explained.

Under the New Paradigm – Sign Error

Because William Gilbert mixes up internal energy and heat added, the result is a sign error. Consult a standard thermodynamics textbook and the first law of thermodynamics will be represented something like this:

dU = dQ + dW

Which in words means:

The change in internal energy equals the heat added plus the work done on the system.

And if we talk about dW as the work done by the system then the sign in front of dW will change. So, if we rewrite the above equation:

dU = dQ – pdV

By the time we get to [WG3] we have two problems.

Here is [WG3] for reference:

dU = CvdT + Ldq + gdz – PdV ….[WG3]

The first problem is that for adiabatic process, no heat is added to (or removed from) the system. So dQ = 0. The author says dU = 0 and makes dQ = change in internal energy (=CvdT + Ldq).

Here is the demonstration of the problem using his equation..

If we have no phase change then Ldq = 0. The gdz term is a mistake – for later consideration – but if we consider an example with no change in height in the atmosphere, we would have (using his equation):

CvdT – PdV = 0 ….[WG3a]

So if the parcel of air expands, doing work on its environment, what happens to temperature?

dV is positive because the volume is increasing. So to keep the equation valid, dT must be positive, which means the temperature must increase.

This means that as the parcel of air does work on its environment, using up energy, its temperature increases – adding energy. A violation of the first law of thermodynamics.

Hopefully, everyone can see that this is not correct. But it is the consequence of the incorrectly stated equation. In any case, I will use both the flawed and the fixed version to demonstrate the second problem.

Under the New Paradigm – Gravity x 2

This problem won’t appear so obvious, which is probably why William Gilbert makes the mistake himself.

In the list of 5 equations, I wrote:

dQ = CvdT + pdV ….[4a]

This is for dry atmospheres, to keep it simple (no Ldq term for water vapor condensing). If you check the Maths Section at the end, you can see that using [4a] we get the result that everyone agrees with for the lapse rate.

I didn’t write:

dQ = CvdT + Mgdz + pdV ….[should this instead be 4a?]

[Note that my equations consider 1 mole of the atmosphere rather than 1 kg which is why “M” appears in front of the gdz term].

So how come I ignored the effect of gravity in the atmosphere yet got the correct answer? Perhaps the derivation is wrong?

The effect of gravity already shows itself via the increase in pressure as we get closer to the surface of the earth.

Atmospheric physics has not been ignoring the effect of gravity and making elementary mistakes. Now for the proof.

If you consult the Maths Section, near the end we have reached the following equation and not yet inserted the equation for the first law of thermodynamics:

pdV – Mgdz = (Cp-Cv)dT ….[10]

Using [10] and “my version” of the first law I successfully derive dT/dz = -g/cp (the right result). Now we will try using William Gilbert’s equation [WG3], with Ldq = 0, to derive the dry adiabatic lapse rate.

0 = CvdT + gdz – PdV ….[WG3b]

and rewriting for one mole instead of 1 kg (and using my terms, see note 1):

pdV = CvdT + Mgdz ….[WG3c]

Inserting WG3c into [10]:

CvdT + Mgdz – Mgdz = (Cp-Cv)dT ….[11]

which becomes:

Cv = (Cp-Cv) ↠ Cp = Cv/2 ….[11a]

A New Paradigm indeed!

Now let’s fix up the sign error in WG3 and see what result we get:

0 = CvdT + gdz + PdV ….[WG3d]

and again rewriting for one mole instead of 1 kg (and again using my terms, see note 1):

pdV = -CvdT – Mgdz ….[WG3e]

Inserting WG3e into [10]:

-CvdT – Mgdz – Mgdz = (Cp-Cv)dT ….[12]

which becomes:

-CvdT – 2Mgdz = CpdT – CvdT ….[12a]

and canceling the -CvdT term from each side:

-2Mgdz = CpdT ….[12b]

So:

dT/dz = -2Mg/Cp, and because specific heat capacity, cp = Cp/M

dT/dz = -2g/cp ….[12c]

The result of “correctly including gravity” is that the dry adiabatic lapse rate ≈ -19.6 K/km.

Note the factor of 2. This is because we are now including gravity twice. The pressure in the atmosphere reduces as we go up – this is because of gravity. When a parcel of air expands due to its change in height, it does work on its surroundings and therefore reduces in temperature – adiabatic expansion. Gravity is already taken into account with the hydrostatic equation.

The Physics of Hand-Waving

The author says:

As we shall see, PV work energy is very important to the understanding of this thermodynamic behavior of the atmosphere, and the thermodynamic role of water vapor condensation plays an important part in this overall energy balance. But this is unfortunately often overlooked or ignored in the more recent climate science literature. The atmosphere is a very dynamic system and cannot be adequately analyzed using static, steady state mental models that primarily focus only on thermal energy.

Emphasis added. This is an unproven assertion because it comes with no references.

In the next stage of the “physics” section, the author doesn’t bother with any equations, making it difficult to understand exactly what he is claiming.

Keeping this gravitational steady state equilibrium in mind, let’s look again at what happens when latent heat is released (condensation) during air parcel ascension.

Latent heat release immediately increases the parcel temperature. But that also results in rapid PV expansion which then results in a drop in parcel temperature. Buoyancy results and the parcel ascends and is driven by the descending pressure profile created by gravity.

The rate of ascension, and the parcel temperature, is a function of the quantity of latent heat released and the PV work needed to overcome the gravitational field to reach a dynamic equilibrium. The more latent heat that is released, the more rapid the expansion / ascension. And the more rapid the ascension, the more rapid is the adiabatic cooling of the parcel. Thus the PV/thermal energy ratio should be a function of the amount of latent heat available for phase conversion at any given altitude. The corresponding physics shows the system will try to force the convecting parcel to approach the dry adiabatic or “gravitational” lapse rate as internal latent heat is released.

For the water vapor remaining uncondensed in the parcel, saturation and subsequent condensation will occur at a more rapid rate if more latent heat is released. In fact if the cooling rate is sufficiently large, super saturation can occur, which can then cause very sudden condensation in greater quantity. Thus the thermal/PV energy ratio is critical in determining the rate of condensation occurring. The higher this ratio, the more complete is the condensation in the parcel, and the lower the specific humidity will be at higher elevations.

I tried (unsuccessfully) to write down some equations to reflect the above paragraphs. The correct approach for the author would be:

- A. Here is what atmospheric physics states now (with references)

- B. Here are the flaws/omissions due to theoretical consideration i), ii), etc

- C. Here is the new derivation (with clear statement of physics principles upon which the new equations are based)

One point I think the author is claiming is that the speed of ascent is a critical factor. Yet the equation for the moist adiabatic lapse rate doesn’t allow for a function of time in the equation.

The (standard) equation has the form (note 2):

dT/dz = g/cp {[1+Lq*/RT]/[1+βLq*/cp]} ….[13]

where q* is the saturation specific humidity and is a function of p & T (i.e. not a constant), and β = 0.067/°C. (See, for example: Atmosphere, Ocean & Climate Dynamics by Marshall & Plumb, 2008)

And this means that if the ascent is – for example – twice as fast, the amount of water vapor condensed at any given height will still be the same. It will happen in half the time, but why will this change any of the thermodynamics of the process?

It might, but it’s not clearly stated, so who can determine the “new physics”?

I can see that something else is claimed to do with the ratio CvdT /pV but I don’t know what it is, or what is behind the claim.

Writing the equations down is important so that other people can evaluate the claim.

And the final “result” of the hand waving is what appears to be the crux of the paper – more humidity at the surface will cause so much “faster” condensation of the moisture that the parcel of air will be drier higher up in the atmosphere. (Where “faster” could mean dT/dt, or could mean dT/dz).

Assuming I understood the claim of the paper correctly it has not been proven from any theoretical considerations. (And I’m not sure I have understood the claim correctly).

Empirical Observations

The heading is actually “Empirical Observations to Verify the Physics”. A more accurate title is “Empirical Observations”.

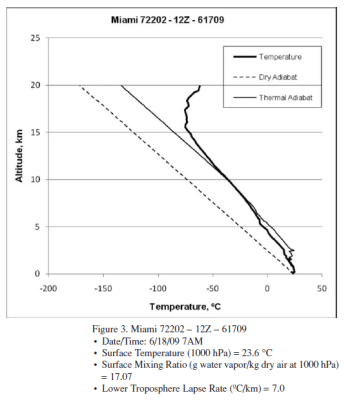

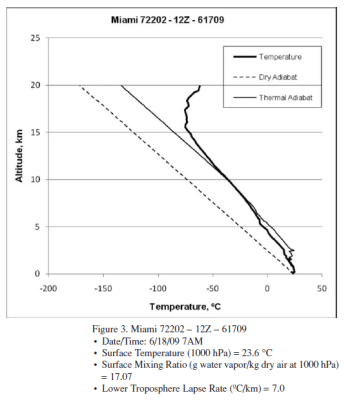

The author provides 3 radiosonde profiles from Miami. Here is one example:

From Gilbert (2010)

Figure 1 – “Thermal adiabat” in the legend = “moist adiabat”

With reference to the 3 profiles, a higher surface humidity apparently leads to complete condensation at a lower altitude.

This is, of course, interesting. This would mean a higher humidity at the surface leads to a drier upper troposphere.

But it’s just 3 profiles. From one location on two different days. Does this prove something or should a few more profiles be used?

A few statements that need backing up:

The lower troposphere lapse rate decreases (slower rate of cooling) with increasing system surface humidity levels, as expected. But the differences in lapse rate are far less than expected based on the relative release of latent heat occurring in the three systems.

What equation determines “than expected”? What result was calculated vs measured? What implications result?

The amount of PV work that occurs during ascension increases markedly as the system surface humidity levels increase, especially at lower altitudes..

How was this calculated? What specifically is the claim? The equation 4a, under adiabatic conditions, with the additional of latent heat reads like this:

CvdT + Ldq + pdV = 0 ….[4a]

Was this equation solved from measured variables of pressure, temperature & specific humidity?

Latent heat release is effectively complete at 7.5 km for the highest surface humidity system (20.06 g/kg) but continues up to 11 km for the lower surface humidity systems (18.17 and 17.07 g/kg). The higher humidity system has seen complete condensation at a lower altitude, and a significantly higher temperature (−17 ºC) than the lower humidity systems (∼ −40 ºC) despite the much greater quantity of latent heat released.

How was this determined?

If it’s true, perhaps the highest humidity surface condition ascended into a colder air front and therefore lost all its water vapor due to the lower temperature?

Why is this (obvious) possibility not commented on or examined??

Textbook Stuff and Why Relative Humidity doesn’t Increase with Height

The radiosonde profiles in the paper are not necessarily following one “parcel” of air.

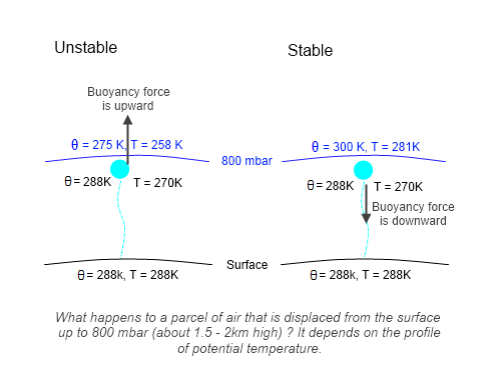

Consider a parcel of air near saturation at the surface. It rises, cools and soon reaches saturation. So condensation takes place, the release of latent heat causes the air to be more buoyant and so it keeps rising. As it rises water vapor is continually condensing and the air (of this parcel) will be at 100% relative humidity.

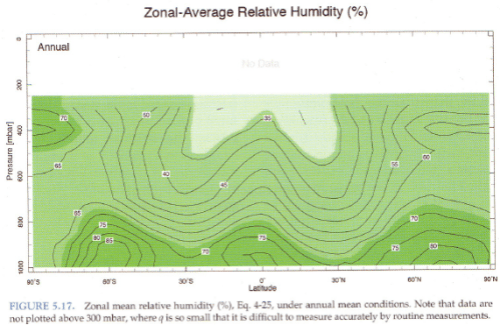

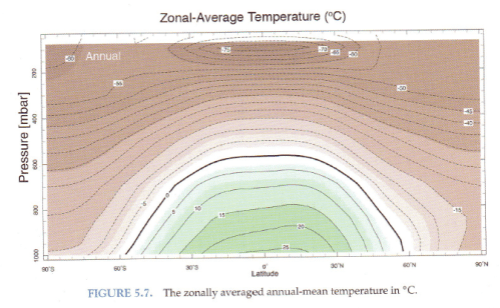

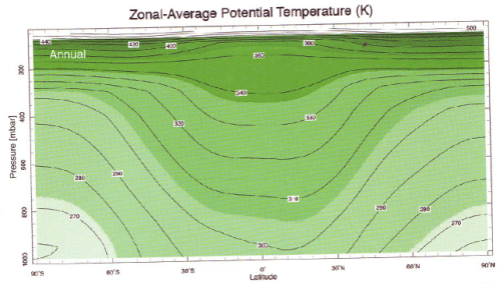

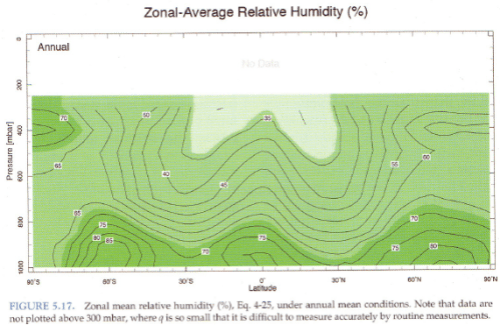

Yet relative humidity doesn’t increase with height, it reduces:

From Marshall & Plumb (2008)

Figure 2

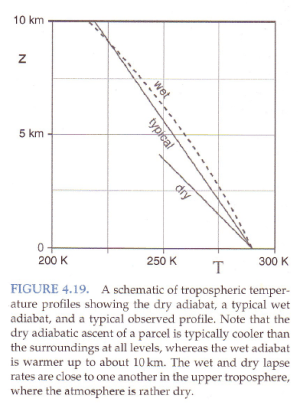

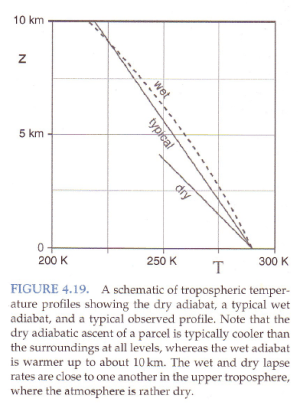

Standard textbook stuff on typical temperature profiles vs dry and moist adiabatic profiles:

From Marshall & Plumb (2008)

Figure 3

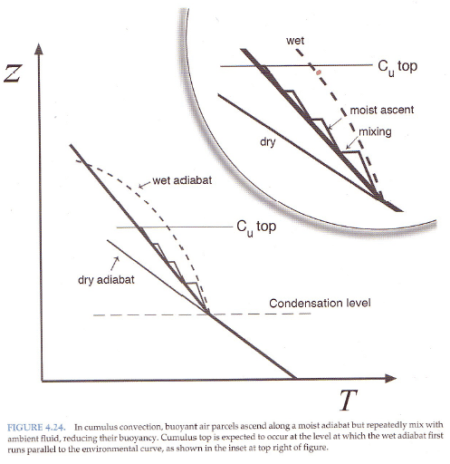

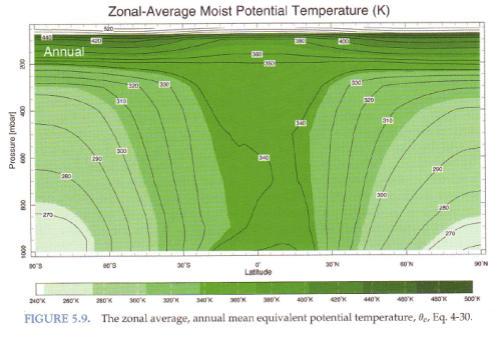

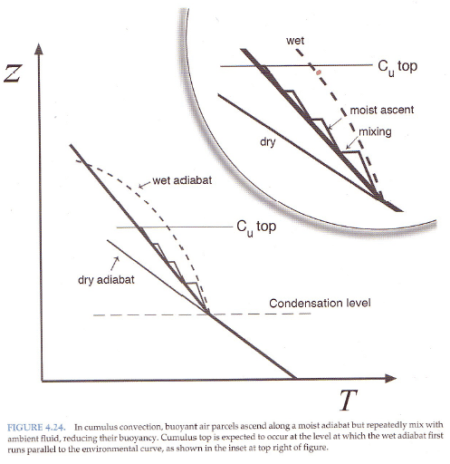

And explaining why the atmosphere under convection doesn’t always follow a moist adiabat:

From Marshall & Plumb (2008)

Figure 4

The atmosphere has descending dry air as well as rising moist air. Mixing of air takes place, which is why relative humidity reduces with height.

Conclusion

The “theory section” of the paper is not a theory section. It has a few equations which are incorrect, followed by some hand-waving arguments that might be interesting if they were turned into equations that could be examined.

It is elementary to prove the errors in the few equations stated in the paper. If we use the author’s equations we derive a final result which contradicts known fundamental thermodynamics.

The empirical results consist of 3 radiosonde profiles with many claims that can’t be tested because the method by which these claims were calculated is not explained.

If it turned out that – all other conditions remaining the same – higher specific humidity at the surface translated into a drier upper troposphere, this would be really interesting stuff.

But 3 radiosonde profiles in support of this claim is not sufficient evidence.

The Maths Section – Real Derivation of Dry Adiabatic Lapse Rate

There are a few ways to get to the final result – this is just one approach. Refer to the original 5 equations under the heading: The Equations for the Lapse Rate.

From [2], pV = RT, differentiate both sides with respect to T:

↠ d(pV)/dT = d(RT)/dT

The left hand side can be expanded as: V.dp/dT + p.dV/dT, and the right hand side = R (as dT/dT=1).

↠ Vdp + pdV = RdT ….[7]

Insert [5], Cp = Cv + R, into [7]:

Vdp + pdV = (Cp-Cv)dT ….[8]

From [1] & [3]:

Vdp = -Mgdz ….[9]

Insert [9] into [8]:

pdV – Mgdz = (Cp-Cv)dT ….[10]

From 4a, under adiabatic conditions, dQ = 0, so CvdT + pdV = 0, and substituting into [10]”

-CvdT – Mgdz = CpdT – CvdT

and adding CvdT to both sides:

-Mgdz = CpdT, or dT/dz = -Mg/Cp ….[11]

and specific heat capacity, cp = Cp/M, so:

dT/dz = g /cp ….[11a]

The correct result, stated as equation [6] earlier.

Notes

Note 1: Definitions in equations. WG2010 has:

- P = pressure, while this article has p = pressure (lower case instead of upper case0

- Cv = heat capacity for 1 kg, this article has Cv = heat capacity for one mole, and cv = heat capacity for 1 kg.

Note 2: The moist adiabatic lapse rate is calculated using the same approach but with an extra term, Ldq, in equation 4a, which accounts for the latent heat released as water vapor condenses.

Read Full Post »

What’s the Palaver? – Kiehl and Trenberth 1997

Posted in Atmospheric Physics, Commentary on June 21, 2011| 123 Comments »

A long time ago I started writing this article. I haven’t yet finished it.

I realized that trying to write it was difficult because the audience criticism was so diverse. Come to me you huddled masses.. This paper, so simple in concept, has become somehow the draw card for “everyone against AGW”. The reasons why are not clear, since the paper is nothing to do with that.

As I review the “critiques” around the blogosphere, I don’t find any consistent objection. That makes it very hard to write about.

So, the reason for posting a half-finished article is for readers to say what they don’t agree with and maybe – if there is a consistent message/question – I will finish the article, or maybe answer the questions here. If readers think that the ideas in the paper somehow violate the first or second law of thermodynamics, please see note 1 and comment in those referenced articles. Not here.

==== part written article ===

In 1997, J. T. Kiehl and Kevin Trenberth’s paper was published, Earth’s Annual Global Mean Energy Budget. (Referred to as KT97 for the rest of this article).

For some reason it has become a very unpopular paper, widely criticized, and apparently viewed as “the AGW paper”.

This is strange as it is a paper which says nothing about AGW, or even possible pre-feedback temperature changes from increases in the inappropriately-named “greenhouse” gases.

KT97 is a paper which attempts to quantify the global average numbers for energy fluxes at the surface and the top of atmosphere. And to quantify the uncertainty in these values.

Of course, many people criticizing the paper believe the values violates the first or second law of thermodynamics. I won’t comment in the main article on the basic thermodynamics laws – for this, check out the links in note 1.

In this article I will try and explain the paper a little. There are many updates from various researchers to the data in KT97, including Trenberth & Kiehl themselves (Trenberth, Fasullo and Kiehl 2009), with later and more accurate figures.

We are looking at this earlier paper because it has somehow become such a focus of attention.

Most people have seen the energy budget diagram as it appears in the IPCC TAR report (2001), but here it is reproduced for reference:

From Kiehl & Trenberth (1997)

History and Utility

Many people have suggested that the KT97 energy budget is some “new invention of climate science”. And at the other end of the spectrum at least one commenter I read was angered by the fact that KT97 had somehow claimed this idea for themselves when many earlier attempts had been made long before KT97.

The paper states:

Compared with “imagining stuff”, reading a paper is occasionally helpful. KT97 is simply updating the field with the latest data and more analysis.

What is an energy budget?

It is an attempt to identify the relative and absolute values of all of the heat transfer components in the system under consideration. In the case of the earth’s energy budget, the main areas of interest are the surface and the “top of atmosphere”.

Why is this useful?

Well, it won’t tell you the likely temperature in Phoenix next month, whether it will rain more next year, or whether the sea level will change in 100 years.. but it helps us understand the relative importance of the different heat transfer mechanisms in the climate, and the areas and magnitude of uncertainty.

For example, the % of reflected solar radiation is now known to be quite close to 30%. That equates to around 103 W/m² of solar radiation (see note 2) that is not absorbed by the climate system. Compared with the emission of radiation from the earth’s climate system into space – 239 W/m² – this is significant. So we might ask – how much does this reflected % change? How much has it changed in the past? See The Earth’s Energy Budget – Part Four – Albedo.

In a similar way, the measurements of absorbed solar radiation and emitted thermal radiation into space are of great interest – do they balance? Is the climate system warming or cooling? How much uncertainty do we have about these measurements.

The subject of the earth’s energy budget tries to address these kind of questions and therefore it is a very useful analysis.

However, it is just one tiny piece of the jigsaw puzzle called climate.

Uncertainty

It might surprise many people that KT97 also say:

And in their conclusion:

It’s true. There are uncertainties and measurement difficulties. Amazing that they would actually say that. Probably didn’t think people would read the paper..

AGW – “Nil points”

What does this paper say about AGW?

What does it say about feedback from water vapor, ice melting and other mechanisms?

What does it say about the changes in surface temperature from doubling of CO2 prior to feedback?

Top of Atmosphere

Since satellites started measuring:

– it has become much easier to understand – and put boundaries around – the top of atmosphere (TOA) energy budget.

The main challenge is the instrument uncertainty. So KT97 consider the satellite measurements. The most accurate results available (at that time) were from five years of ERBE data (1985-1989).

From those results, the outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) from ERBE averaged 235 W/m² while the absorbed solar radiation averaged 238 W/m². Some dull discussion of error estimates from earlier various papers follows. The main result being that the error estimates are in the order of 5W/m², so it isn’t possible to pin down the satellite results any closer than that.

KT97 concludes:

What are they saying? That – based on the measurements and error estimates – a useful working assumption is that the earth (over this time period) is in energy balance and so “pick the best number” to represent that. Reflected solar radiation is the hardest to measure accurately (because it can be reflected in any direction) so we assume that the OLR is the best value to work from.

If the absorbed solar radiation and the OLR had been, say, 25 W/m² apart then the error estimates couldn’t have bridged this gap. And the choices would have been:

So all the paper is explaining about the TOA results is that the measurement results don’t justify concluding that the earth is out of energy balance and therefore they pick the best number to represent the TOA fluxes. That’s it. This shouldn’t be very controversial.

And also note that during this time period the ocean heat content (OHC) didn’t record any significant increase, so an assumption of energy balance during this period is reasonable.

And, as with any review paper, KT97 also include the results from previous studies, explaining where they agree and where they differ and possible/probable reasons for the differences.

In their later update of their paper (2009) they use the results of a climate model for the TOA imbalance. This comes to 0.9 W/m². In the context of the uncertainties they discuss this is not so significant. It is simply a matter of whether the TOA fluxes balance or not. This is something that is fundamentally unknown over a given 5-year or decadal time period.

As an exercise for the interested student, if you review KT97 with the working assumption that the TOA fluxes are out of balance by 1W/m², what changes of note take place to the various values in the 1997 paper?

Surface Fluxes

This is the more challenging energy balance. At TOA we have satellites measuring the radiation quite comprehensively – and we have only radiation as the heat transfer mechanism for incoming and outgoing energy.

At the surface the measurement systems are less complete. Why is that?

Firstly, we have movement of heat from the surface via latent heat and sensible heat – as well as radiation.

Secondly, satellites can only measure only a small fraction of the upward emitted surface radiation and none of the downward radiation at the surface.

Surface Fluxes – Radiation

To calculate the surface radiation, upward and downward, we need to rely on theory, on models.

Well, that’s what you might think if you read a lot of blogs that have KT97 on their hit list. It’s easy to make claims.

In fact, if we want to know on a global annual average basis what the upward and downward longwave fluxes are, and if we want to know the solar (shortwave) fluxes that reach the surface (vs absorbed in the atmosphere), we need to rely on models. This is simply because we don’t have 1,000’s of high quality radiation-measuring stations.

Instead we do have a small network of high-quality monitoring stations for measuring downward radiation – the BSRN (baseline surface radiation network) was established by the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP) in the early 1990’s. See The Amazing Case of “Back Radiation”.

The important point is that, for the surface values of downward solar and downward longwave radiation we can check the results of theory against measurements in the places where measurements are available. This tells us whether models are accurate or not.

To calculate the values of surface fluxes with the resolution to calculate the global annual average we need to rely on models. For many people, their instinctive response is that obviously this is not accurate. Instinctive responses are not science, though.

Digression – Many Types of Models

There are many different types of models. For example, if we want to know the value of the DLR (downward longwave radiation) at the surface on Nov 1st, 2210 we need to be sure that some important parameters are well-known for this date. We would need to know the temperature of the atmosphere as a function of height through the atmosphere – and also the concentration of CO2, water vapor, methane – and so on. We would need to predict all of these values successfully for Nov 1st, 2210.

The burden of proof is quite high for this “prediction”.

However, if we want to know the average value of DLR for 2009 we need to have a record of these parameters at lots of locations and times and we can do a proven calculation for DLR at these locations and times.

An Analogy – It isn’t much different from calculating how long the water will take to boil on the stove – we need to know how much water, the initial temperature of the water, the atmospheric temperature and what level you turned the heat to. If we want to predict this value for the future we will need to know what these values will be in the future. But to calculate the past is easy – if we already have a record of these parameters.

See Theory and Experiment – Atmospheric Radiation for examples of verifying theory against experiment.

End of Digression

And if we want to know the upward fluxes we need to know the reflected portion.

Related Articles

Kiehl & Trenberth and the Atmospheric Window

The Earth’s Energy Budget – Part One – a few climate basics.

The Earth’s Energy Budget – Part Two – the important concept of energy balance at top of atmosphere.

References

Earth’s Annual Global Mean Energy Budget, Kiehl & Trenberth, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (1997) – free paper

Earth’s Global Energy Budget, Trenberth, Fasullo & Kiehl, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (2009) – free paper

Notes

Note 1 – The First Law of Thermodynamics is about the conservation of energy. Many people believe that because the temperature is higher at the surface than the top of atmosphere this somehow violates this first law. Check out Do Trenberth and Kiehl understand the First Law of Thermodynamics? as well as the follow-on articles.

The Second Law of Thermodynamics is about entropy increasing, due to heat flowing from hotter to colder. Many have created an imaginary law which apparently stops energy from radiation from a colder body being absorbed by a hotter body. Check out these articles:

Amazing Things we Find in Textbooks – The Real Second Law of Thermodynamics

The Three Body Problem

Absorption of Radiation from Different Temperature Sources

The Amazing Case of “Back Radiation” – Part Three and Part One and Part Two

Note 2 – When comparing solar radiation with radiation emitted by the climate system there is a “comparison issue” that has to be taken into account. Solar radiation is “captured” by an area of πr² (the area of a disc) because the solar radiation comes from a point source a long way away. But terrestrial radiation is emitted over the whole surface of the earth, an area of 4πr². So if we are talking about W/m² either we need to multiply terrestrial radiation by a factor of 4 to equate the two, or divide solar radiation by a factor of 4 to equate the two. The latter is conventionally chosen.

More about this in The Earth’s Energy Budget – Part One

Read Full Post »