In Part One we saw:

- some trends based on real radiosonde measurements

- some reasons why long term radiosonde measurements are problematic

- examples of radiosonde measurement “artifacts” from country to country

- the basis of reanalyses like NCEP/NCAR

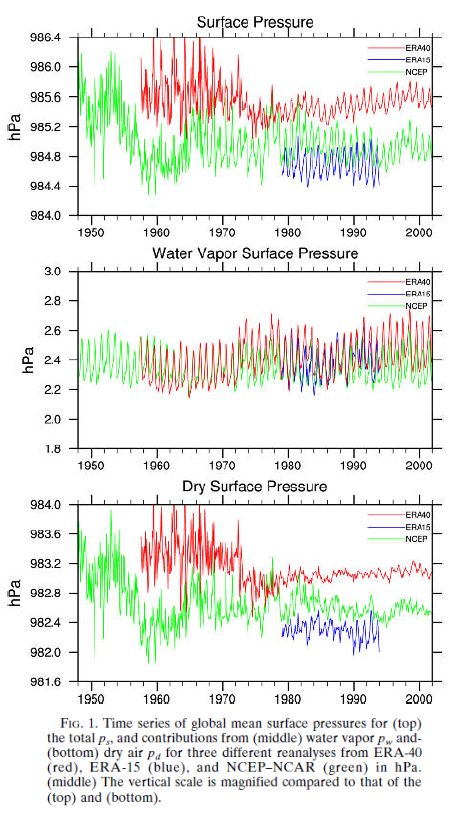

- an interesting comparison of reanalyses against surface pressure measurements

- a comparison of reanalyses against one satellite measurement (SSMI)

But we only touched on the satellite data (shown in Trenberth, Fasullo & Smith in comparison to some reanalysis projects).

Wentz & Schabel (2000) reviewed water vapor, sea surface temperature and air temperature from various satellites. On water vapor they said:

..whereas the W [water vapor] data set is a relatively new product beginning in 1987 with the launch of the special sensor microwave imager (SSM/I), a multichannel microwave radiometer. Since 1987 four more SSM/I’s have been launched, providing an uninterrupted 12-year time series. Imaging radiometers before SSM/I were poorly calibrated, and as a result early water-vapour studies (7) were unable to address climate variability on interannual and decadal timescales.

The advantage of SSMI is that it measures the 22 GHz water vapor line. Unlike measurements in the IR around 6.7 μm (for example the HIRS instrument) which require some knowledge of temperature, the 22 GHz measurement is a direct reflection of water vapor concentration. The disadvantage of SSMI is that it only works over the ocean because of the low ocean emissivity (but variable land emissivity). And SSMI does not provide any vertical resolution of water vapor concentration, only the “total precipitable water vapor” (TPW) also known as “column integrated water vapor” (IWV).

The algorithm, verification and error analysis for the SSMI can be seen in Wentz’s 1997 JGR paper: A well-calibrated ocean algorithm for special sensor microwave / imager.

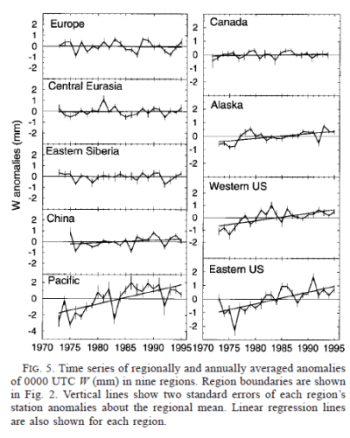

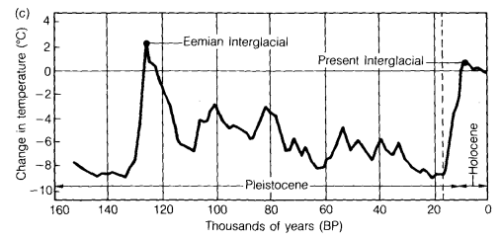

Here is Wentz & Schabel’s graph of IWV over time (shown as W in their figure):

From Wentz & Schabel (2000)

Figure 1 – Region captions added to each graph

They calculate, for the short period in question (1988-1998):

- 1.9%/decade for 20°N – 60°N

- 2.1%/decade for 20°S – 20°N

- 1.0%/decade for 20°S – 60°S

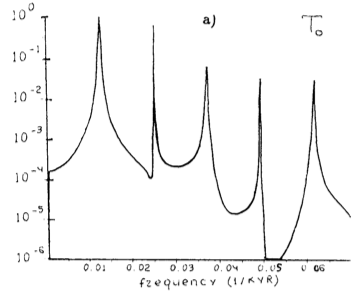

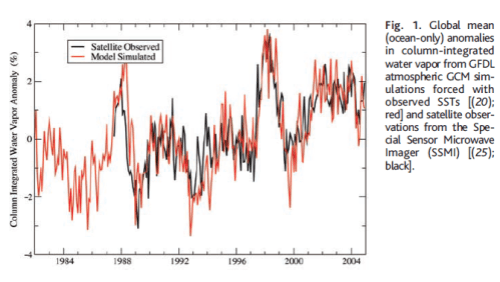

Soden et al (2005) take the dataset a little further and compare it to model results:

From Soden et al (2005)

Figure 2

They note the global trend of 1.4 ± 0.78 %/decade.

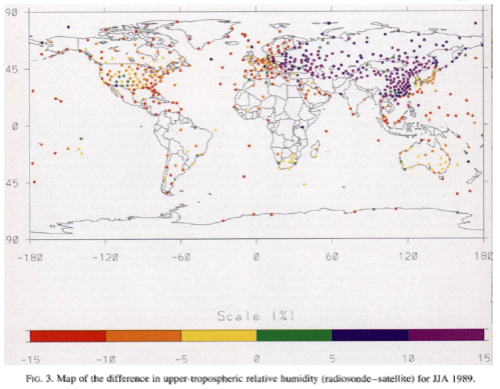

As their paper is more about upper tropospheric water vapor they also evaluate the change in channel 12 of the HIRS instrument (High Resolution Infrared Radiometer Sounder):

The radiance channel centered at 6.7 μm (channel 12) is sensitive to water vapor integrated over a broad layer of the upper troposphere (200 to 500 hPa) and has been widely used for studies of upper tropospheric water vapor. Because clouds strongly attenuate the infrared radiation, we restrict our analysis to clear-sky radiances in which the upwelling radiation in channel 12 is not affected by clouds.

The change in radiance from channel 12 is approximately zero over the time period, which for technical reasons (see note 1) corresponds to roughly constant relative humidity in that region over the period from the early 1980’s to 2004. You can read the technical explanation in their paper, but as we are focusing on total water vapor (IWV) we will leave a discussion over UTWV for another day.

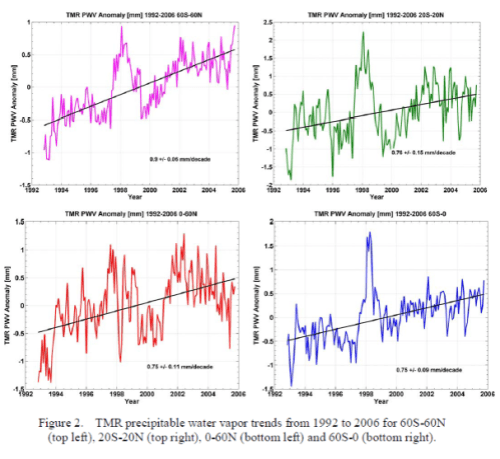

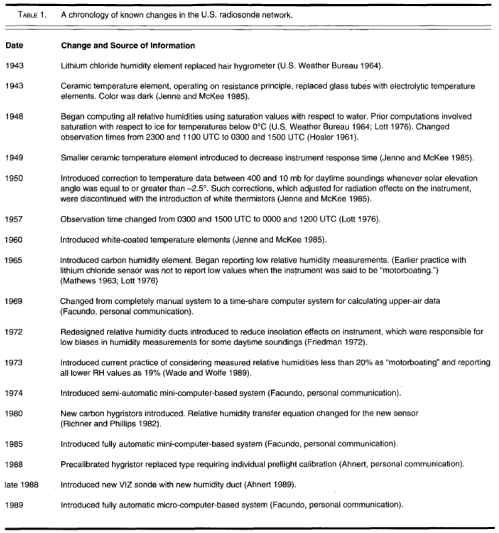

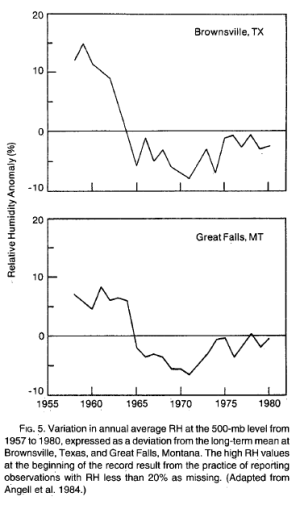

Updated Radiosonde Trends

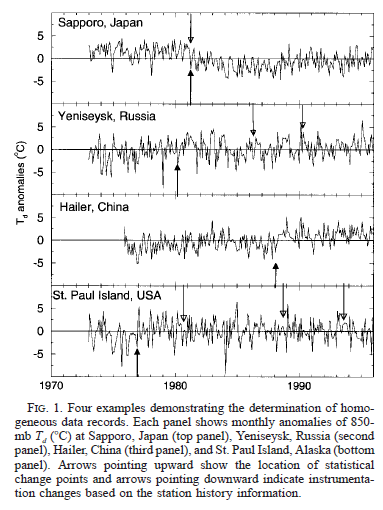

Durre et al (2009) updated radiosonde trends in their 2009 paper. There is a lengthy extract from the paper in note 2 (end of article) to give insight into why radiosonde data cannot just be taken “as is”, and why a method has to be followed to identify and remove stations with documented or undocumented instrument changes.

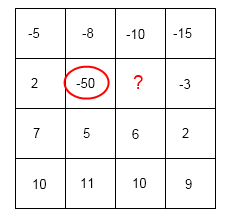

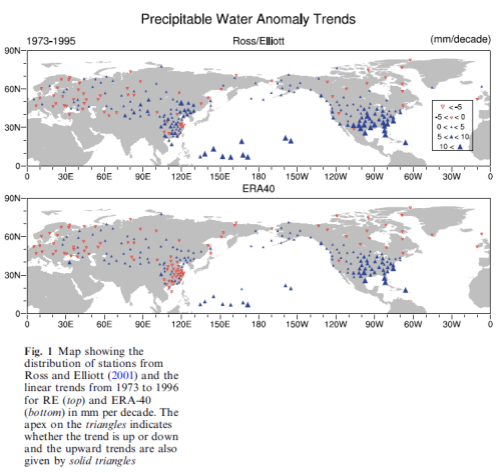

Importantly they note, as with Ross & Elliott 2001:

..Even though the stations were located in many parts of the globe, only a handful of those that qualified for the computation of trends were located in the Southern Hemisphere. Consequently, the trend analysis itself was restricted to the Northern Hemisphere as in that of RE01..

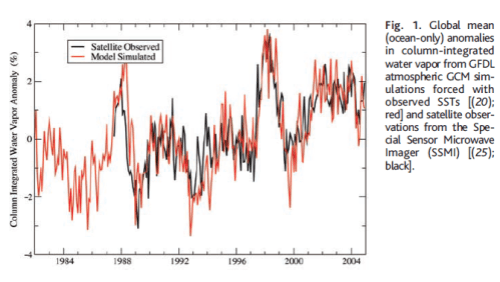

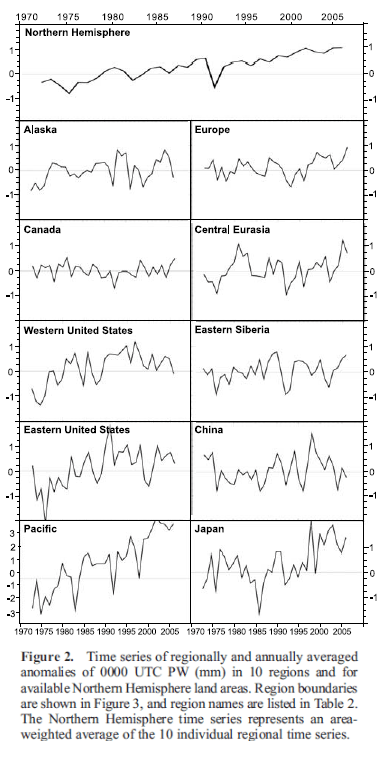

Here are their time-based trends:

From Durre et al (2009)

Figure 3

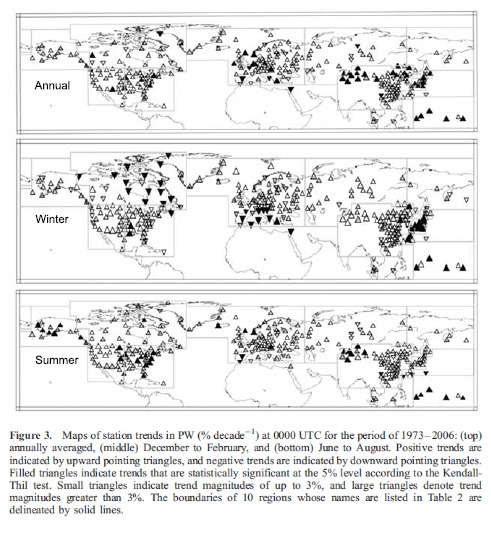

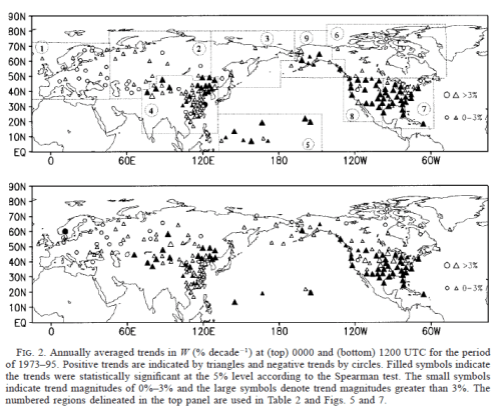

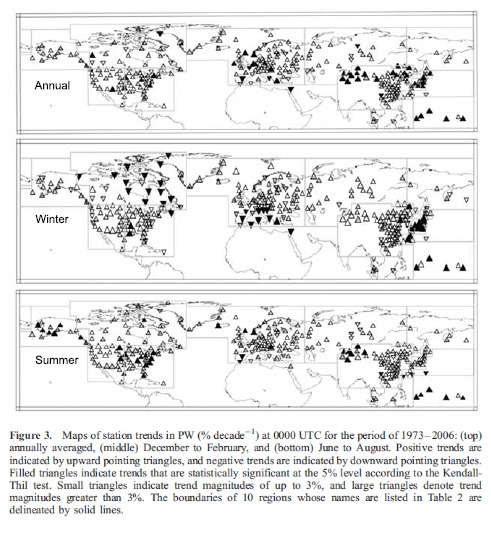

And a map of trends:

From Durre et al (2009)

Figure 4

Note the sparse coverage of the oceans and also the land regions in Africa and Asia, except China.

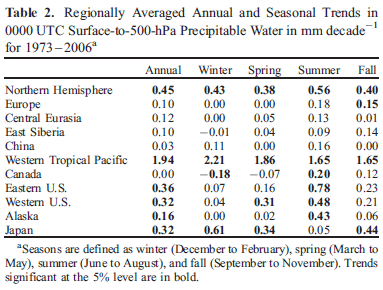

And their table of results:

From Durre et al (2009)

Figure 5

A very interesting note on the effect of their removal of stations based on detection of instrument changes and other inhomogeneities:

Compared to trends based on unadjusted PW data (not shown), the trends in Table 2 are somewhat more positive. For the Northern Hemisphere as a whole, the unadjusted trend is 0.22 mm/decade�, or 0.23 mm/decade� less than the adjusted trend.

This tendency for the adjustments to yield larger increases in PW is consistent with the notion that improvements in humidity measurements and observing practices over time have introduced an artificial drying into the radiosonde record (e.g., RE01).

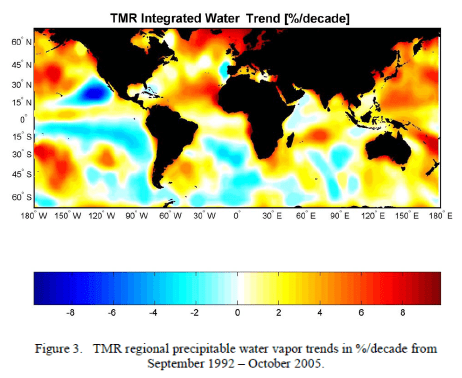

TOPEX Microwave

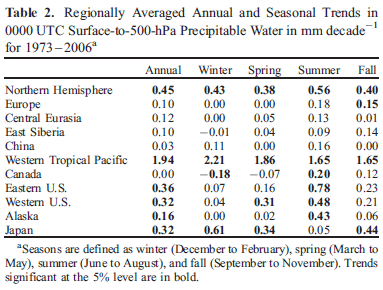

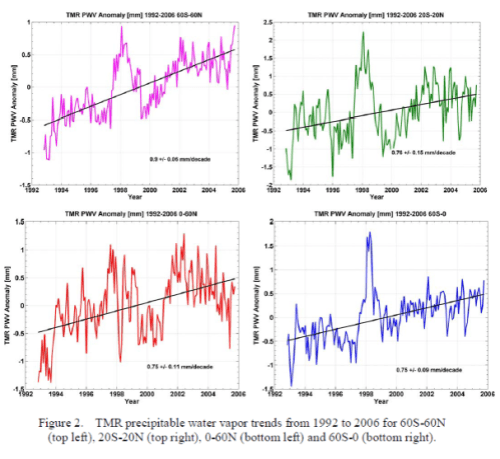

Brown et al (2007) evaluated data from the Topex Microwave Radiometer (TMR). This is included on the Topex/Poseiden oceanography satellite and is dedicated to measuring the integrated water vapor content of the atmosphere. TMR is nadir pointing and measures the radiometric brightness temperature at 18, 21 and 37 GHz. As with SSMI, it only provides data over the ocean.

For the period of operation of the satellite (1992 – 2005) they found the trend of 0.90 ± 0.06 mm/decade:

From Brown et al (2007)

Figure 6 – Click for a slightly larger view

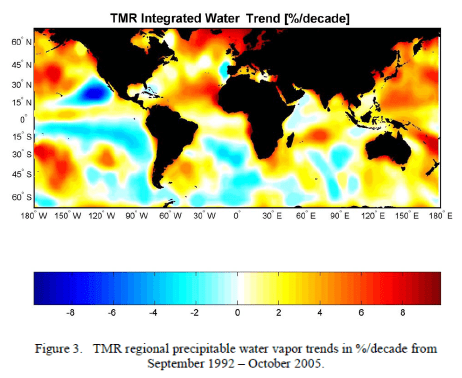

And a map view:

From Brown et al (2007)

Figure 7

Paltridge et al (2009)

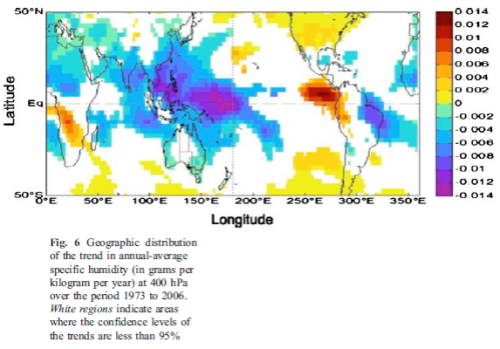

Paltridge, Arking & Pook (2009) – P09 – take a look at the NCEP/NCAR reanalysis project from 1973 – 2007. They chose 1973 as the start date for the reasons explained in Part One – Elliott & Gaffen have shown that pre-1973 data has too many problems. They focus on humidity data below 500mbar as the measurement of humidity at higher altitudes and lower temperatures are more prone to radiosonde problems.

The NCEP/NCAR data shows positive trends below 850 mbar (=hPa) in all regions, negative trends above 850 mbar in the tropics and midlatitudes, and negative trends above 600 mbar in the northern midlatitudes.

Here are the water vapor trends vs height (pressure) for both relative humidity and specific humidity:

From Paltridge et al (2009)

Figure 8

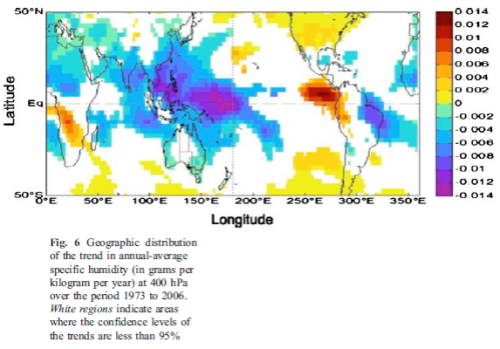

And here is the map of trends:

from Paltridge et al (2009)

Figure 9

They comment on the “boundary layer” vs “free troposphere” issue.. In brief the boundary layer is that “well-mixed layer” close to the surface where the friction from the ground slows down the atmospheric winds and results in more turbulence and therefore a well-mixed layer of atmosphere. This is typically around 300m to 1000m high (there is no sharp “cut off”). At the ocean surface the atmosphere tends to be saturated (if the air is still) and so higher temperatures lead to higher specific humidities. (See Clouds and Water Vapor – Part Two if this is a new idea). Therefore, the boundary layer is uncontroversially expected to increase its water vapor content with temperature increases. It is the “free troposphere” or atmosphere above the boundary layer where the debate lies.

They comment:

It is of course possible that the observed humidity trends from the NCEP data are simply the result of problems with the instrumentation and operation of the global radiosonde network from which the data are derived.

The potential for such problems needs to be examined in detail in an effort rather similar to the effort now devoted to abstracting real surface temperature trends from the face-value data from individual stations of the international meteorological networks.

In the meantime, it is important that the trends of water vapor shown by the NCEP data for the middle and upper troposphere should not be “written off” simply on the basis that they are not supported by climate models—or indeed on the basis that they are not supported by the few relevant satellite measurements.

There are still many problems associated with satellite retrieval of the humidity information pertaining to a particular level of the atmosphere— particularly in the upper troposphere. Basically, this is because an individual radiometric measurement is a complicated function not only of temperature and humidity (and perhaps of cloud cover because “cloud clearing” algorithms are not perfect), but is also a function of the vertical distribution of those variables over considerable depths of atmosphere. It is difficult to assign a trend in such measurements to an individual cause.

Since balloon data is the only alternative source of information on the past behavior of the middle and upper tropospheric humidity and since that behavior is the dominant control on water vapor feedback, it is important that as much information as possible be retrieved from within the “noise” of the potential errors.

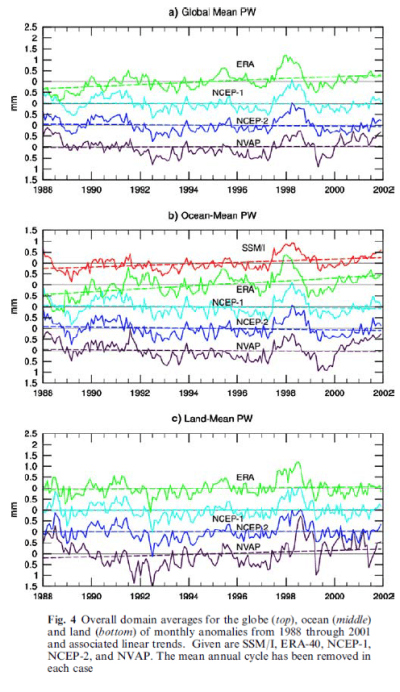

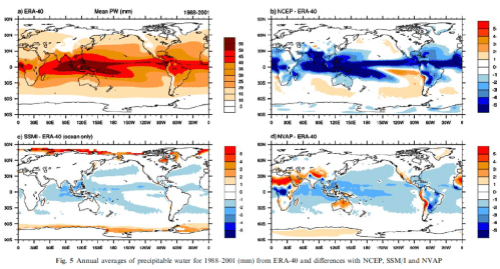

So what has P09 added to the sum of knowledge? We can already see the NCEP/NCAR trends in Trends and variability in column-integrated atmospheric water vapor by Trenberth et al from 2005.

Did the authors just want to take the reanalysis out of the garage, drive it around the block a few times and park it out front where everyone can see it?

No, of course not!

– I hear all the NCEP/NCAR believers say.

One of our commenters asked me to comment on Paltridge’s reply to Dessler (which was a response to Paltridge..), and linked to another blog article. It seems like even the author of that blog article is confused about NCEP/NCAR. This reanalysis project (as explained in Part One), is a model output not a radiosonde dataset:

Humidity is in category B – ‘although there are observational data that directly affect the value of the variable, the model also has a very strong influence on the value ‘

And for those people who have a read of Kalnay’s 1996 paper describing the project they will see that with the huge amount of data going into the model, the data wasn’t quality checked by human inspection on the way in. Various quality control algorithms attempt to (automatically) remove “bad data”.

This is why we have reviewed Ross & Elliott (2001) and Durre et al (2009). These papers review the actual radiosonde data and find increasing trends in IWV. They also describe in a lot of detail what kind of process they had to go through to produce a decent dataset. The authors of both papers also both explained that they could only produce a meaningful trend for the northern hemisphere. There is not enough quality data for the southern hemisphere to even attempt to produce a trend.

And Durre et al note that when they use the complete dataset the trend is half that calculated with problematic data removed.

This is the essence of the problem with Paltridge et al (2009)

Why is Ross & Elliot (2001) not reviewed and compared? If Ross & Elliott found that Southern Hemisphere trends could not be calculated because of the sparsity of quality radiosonde data, why doesn’t P09 comment on that? Perhaps Ross & Elliott are wrong. But no comment from P09. (Durre et al find the same problem with SH data, and probably too late for P09 but not too late for the 2010 comments the authors have been making).

In The Mass of the Atmosphere: A Constraint on Global Analyses, Trenberth & Smith pointed out clear problems with NCEP/NCAR vs ERA-40. Perhaps Trenberth and Smith are wrong. Or perhaps there is another way to understand these results. But no comment on this from P09.

P09 comment on the issues with satellite humidity retrieval for different layers of the atmosphere but no comment on the results from the microwave SSMI which has a totally different algorithm to retrieve IWV. And it is important to understand that they haven’t actually demonstrated a problem with satellite measurements. Let’s review their comment:

In the meantime, it is important that the trends of water vapor shown by the NCEP data for the middle and upper troposphere should not be “written off” simply on the basis that they are not supported by climate models—or indeed on the basis that they are not supported by the few relevant satellite measurements.

The reader of the paper wouldn’t know that Trenberth & Smith have demonstrated an actual reason for preferring ERA-40 (if any reanalysis is to be used).

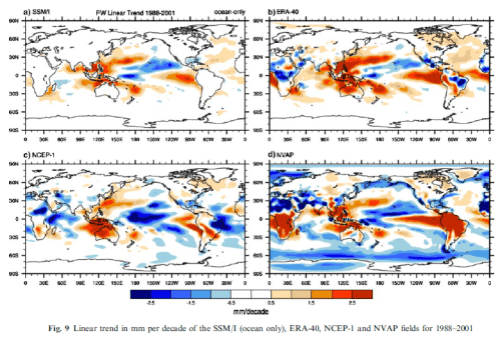

The reader of the paper might understand “a few relevant satellite measurements” as meaning there wasn’t much data from satellites. If you review figure 4 you can see that the quality radiosonde data is essentially mid-latitude northern hemisphere land. Satellites – that is, multiple satellites with different instruments at different frequencies – have covered the oceans much much more comprehensively than radiosondes. Are the satellites all wrong?

The reader of the paper would think that the dataset has been apparently ditched because it doesn’t fit climate models.

This is probably the view of Paltridge, Arking & Pook. But they haven’t demonstrated it. They have just implied it.

Dessler & Davis (2010)

Dessler & Davis responded to P09. They plot some graphs from 1979 to present. The reason for plotting graphs from 1979 is because this is when the satellite data was introduced. And all of the reanalysis projects, except NCEP/NCAR incorporated satellite humidity data. (NCEP/NCAR does incorporate satellite data for some other fields).

Basically when data from a new source is introduced, even if it is more accurate, it can introduce spurious trends and even in opposite direction to the real trends. This was explained in Part One under the heading Comparing Reanalysis of Humidity. So trend analysis usually takes place over periods of consistent data sources.

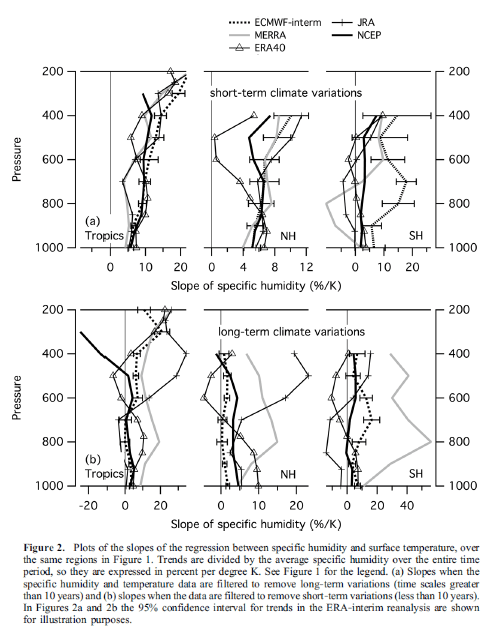

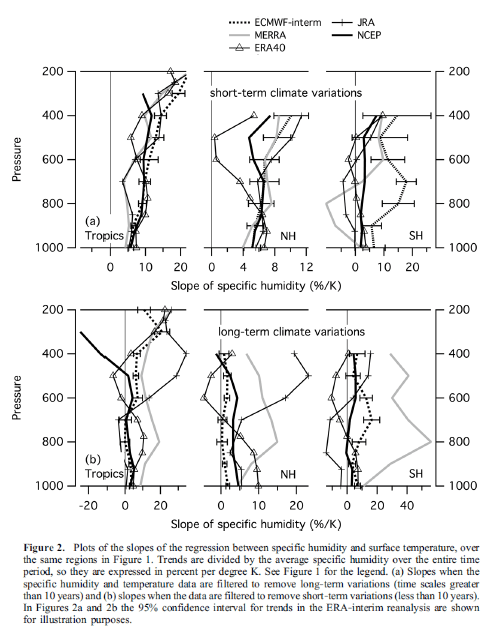

This figure contrasts short term relationships between temperature and humidity with long term relationships:

From Dessler & Davis (2010)

Figure 10

If the blog I referenced earlier is anything to go by, the primary reason for producing this figure has been missed. And as that blog article seemed to not comprehend that NCEP/NCAR is a reanalysis (= model output) it’s not so surprising.

Dessler & Davis said:

There is poorer agreement among the reanalyses, particularly compared to the excellent agreement for short‐term fluctuations. This makes sense: handling data inhomogeneities will introduce long‐term trends in the data but have less effect on short‐term trends. This is why long term trends from reanalyses tend to be looked at with suspicion [e.g., Paltridge et al., 2009; Thorne and Vose, 2010; Bengtsson et al., 2004].

[Emphasis added]

They are talking about artifacts of the model (NCEP/NCAR). In the short term the relationship between humidity and temperature agree quite well among the different reanalyses. But in the longer term NCEP/NCAR doesn’t – demonstrating that it is likely introducing biases.

The alternative, as Dessler & Davis explain, is that there is somehow an explanation for a long term negative feedback (temperature and water vapor) with a short term positive feedback.

If you look around the blog world, or at say, Professor Lindzen you don’t find this. You find arguments about why short term feedback is negative. Not an argument that short term is positive and yet long term is negative.

I agree that many people say: “I don’t know, it’s complicated, perhaps there is a long term negative feedback..” and I respect that point of view.

But in the blog article pointed to me by our commenter in Part One, the author said:

JGR let some decidedly unscientific things slip into that Dessler paper. One of the reasons provided is nothing more than a form of argument from ignorance: “there’s no theory that explains why the short term might be different to the long term”.

Why would any serious scientist admit that they don’t have the creativity or knowledge to come up with some reasons, and worse, why would they think we’d find that ignorance convincing?

..It’s not that difficult to think of reasons why it’s possible that humidity might rise in the short run, but then circulation patterns or other slower compensatory effects shift and the long run pattern is different. Indeed they didn’t even have to look further than the Paltridge paper they were supposedly trying to rebut (see Garth’s writing below). In any case, even if someone couldn’t think of a mechanism in a complex unknown system like our climate, that’s not “a reason” worth mentioning in a scientific paper.

The point that seems to have been missed is this is not a reason to ditch the primary dataset but instead a reason why NCEP/NCAR is probably flawed compared with all the other reanalyses. And compared with the primary dataset. And compared with multiple satellite datasets.

This is the issue with reanalyses. They introduce spurious biases. Bengsston explained how (specifically for ERA-40). Trenberth & Smith have already demonstrated it for NCEP/NCAR. And now Dessler & Davis have simply pointed out another reason for taking that point of view.

The blog writer thinks that Dessler is trying to ditch the primary dataset because of an argument from ignorance. I can understand the confusion.

It is still confusion.

One last point to add is that Dessler & Davis also added the very latest in satellite water vapor data – the AIRS instrument from 2003. AIRS is a big step forward in satellite measurement of water vapor, a subject for another day.

AIRS also shows the same trends as the other reanalyses and different from NCEP/NCAR.

A Scenario

Before reaching the conclusion I want to throw a scenario out there. It is imaginary.

Suppose that there were two sources of data for temperature over the surface of the earth – temperature stations and satellite. Suppose the temperature stations were located mainly in mid-latitude northern hemisphere locations. Suppose that there were lots of problems with temperature stations – instrument changes & environmental changes close to the temperature stations (we will call these environmental changes “UHI”).

Suppose the people who had done the most work analyzing the datasets and trying to weed out the real temperature changes from the spurious ones had demonstrated that the temperature had decreased over northern hemisphere mid-latitudes. And that they had claimed that quality southern hemisphere data was too “thin on the ground” to really draw any conclusions from.

Suppose that satellite data from multiple instruments, each using different technology, had also demonstrated that temperatures were decreasing over the oceans.

Suppose that someone fed the data from the (mostly NH) land-based temperature stations – without any human intervention on the UHI and instrument changes – into a computer model.

And suppose this computer model said that temperatures were increasing.

Imagine it, for a minute. I think we can picture the response.

And yet, this is a similar situation that we are confronted with on integrated water vapor (IWV). I have tried to think of a reason why so many people would be huge fans of this particular model output. I did think of one, but had to reject it immediately as being ridiculous.

I hope someone can explain why NCEP/NCAR deserves the fan club it has currently built up.

Conclusion

Radiosonde datasets, despite their problems, have been analyzed. The researchers have found positive water vapor trends for the northern hemisphere with these datasets. As far as I know, no one has used radiosonde datasets to find the opposite.

Radiosonde datasets provide excellent coverage for mid-latitude northern hemisphere land, and, with a few exceptions, poor coverage elsewhere.

Satellites, using IR and microwave, demonstrate increasing water vapor over the oceans for the shorter time periods in which they have been operating.

Reanalysis projects have taken in various data sources and, using models, have produced output values for IWV (total water vapor) with mixed results.

Reanalysis projects all have the benefit of convenience, but none are perfect. The dry mass of the atmosphere, which should be constant within noise errors unless a new theory comes along, demonstrates that NCEP/NCAR is worse than ERA-40.

ERA-40 demonstrates increasing IWV. NCEP/NCAP demonstrates negative IWV.

Some people have taken NCEP/NCAR for a drive around the block and parked it in front of their house and many people have wandered down the street to admire it. But it’s not the data. It’s a model.

Perhaps Paltridge, Arking or Pook can explain why NCEP/NCAR is a quality dataset. Unfortunately, their paper doesn’t demonstrate it.

It seems that some people are really happy if one model output or one dataset or one paper says something different from what 5 or 10 or 100 others are saying. If that makes you, the reader, happy, then at least the world has less deaths from stress.

In any field of science there are outliers.

The question on this blog at least, is what can be proven, what can be demonstrated and what evidence lies behind any given claim. From this blog’s perspective, the fact that outliers exist isn’t really very interesting. It is only interesting to find out if in fact they have merit.

In the world of historical climate datasets nothing is perfect. It seems pretty clear that integrated water vapor has been increasing over the last 20-30 years. But without satellites, even though we have a long history of radiosonde data, we have quite a limited dataset geographically.

If we can only use radiosonde data perhaps we can just say that water vapor has been increasing over northern hemisphere mid-latitude land for nearly 40 years. If we can use satellite as well, perhaps we can say that water vapor has been increasing everywhere for over 20 years.

If we can use the output from reanalysis models and do a lucky dip perhaps we can get a different answer.

And if someone comes along, analyzes the real data and provides a new perspective then we can all have another review.

References

On the Utility of Radiosonde Humidity Archives for Climate Studies, Elliot & Gaffen, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (1991)

Relationships between Tropospheric Water Vapor and Surface Temperature as Observed by Radiosondes, Gaffen, Elliott & Robock, Geophysical Research Letters(1992)

Column Water Vapor Content in Clear and Cloudy Skies, Gaffen & Elliott, Journal of Climate (1993)

On Detecting Long Term Changes in Atmospheric Moisture, Elliot, Climate Change (1995)

Tropospheric Water Vapor Climatology and Trends over North America, 1973-1993, Ross & Elliot, Journal of Climate (1996)

An assessment of satellite and radiosonde climatologies of upper-tropospheric water vapor, Soden & Lanzante, Journal of Climate (1996)

The NCEP/NCAR 40-year Reanalysis Project, Kalnay et al, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (1996)

Precise climate monitoring using complementary satellite data sets, Wentz & Schabel, Nature (2000)

Radiosonde-Based Northern Hemisphere Tropospheric Water Vapor Trends, Ross & Elliott, Journal of Climate (2001)

An analysis of satellite, radiosonde, and lidar observations of upper tropospheric water vapor from the Atmospheric Radiation Measurement Program, Soden et al, Journal of Geophysical Research (2005)

The Radiative Signature of Upper Tropospheric Moistening, Soden et al, Science (2005)

The Mass of the Atmosphere: A Constraint on Global Analyses, Trenberth & Smith, Journal of Climate (2005)

Trends and variability in column-integrated atmospheric water vapor, Trenberth et al, Climate Dynamics (2005)

Can climate trends be calculated from reanalysis data? Bengtsson et al, Journal of Geophysical Research (2005)

Ocean Water Vapor and Cloud Burden Trends Derived from the Topex Microwave Radiometer, Brown et al, Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 2007. IGARSS 2007. IEEE International (2007)

Radiosonde-based trends in precipitable water over the Northern Hemisphere: An update, Durre et al, Journal of Geophysical Research (2009)

Trends in middle- and upper-level tropospheric humidity from NCEP reanalysis data, Paltridge et al, Theoretical Applied Climatology (2009)

Trends in tropospheric humidity from reanalysis systems, Dessler & Davis, Journal of Geophysical Research (2010)

Notes

Note 1: The radiance measurement in this channel is a result of both the temperature of the atmosphere and the amount of water vapor. If temperature increases radiance increases. If water vapor increases it attenuates the radiance. See the slightly more detailed explanation in their paper.

Note 2: Here is a lengthy extract from Durre et al (2009), partly because it’s not available for free, and especially to give an idea of the issues arising from trying to extract long term climatology from radiosonde data and, therefore, careful approach that needs to be taken.

Emphasis added in each case:

From the IGRA+RE01 data, stations were chosen on the basis of two sets of requirements: (1) criteria that qualified them for use in the homogenization process and (2) temporal completeness requirements for the trend analysis.

In order to be a candidate for homogenization, a 0000 UTC or 1200 UTC time series needed to both contain at least two monthly means in each of the 12 calendar months during 1973–2006 and have at least five qualifying neighbors (see section 2.2). Once adjusted, each time series was tested against temporal completeness requirements analogous to those used by RE01; it was considered sufficiently complete for the calculation of a trend if it contained no more than 60 missing months, and no data gap was longer than 36 consecutive months.

Approximately 700 stations were processed through the pairwise homogenization algorithm (hereinafter abbreviated as PHA) at each of the nominal observation times. Even though the stations were located in many parts of the globe, only a handful of those that qualified for the computation of trends were located in the Southern Hemisphere.

Consequently, the trend analysis itself was restricted to the Northern Hemisphere as in that of RE01. The 305 Northern Hemisphere stations for 0000 UTC and 280 for 1200 UTC that fulfilled the completeness requirements covered mostly North America, Greenland, Europe, Russia, China, and Japan.

Compared to RE01, the number of stations for which trends were computed increased by more than 100, and coverage was enhanced over Greenland, Japan, and parts of interior Asia. The larger number of qualifying

stations was the result of our ability to include stations that were sufficiently complete but contained significant inhomogeneities that required adjustment.

Considering that information on these types of changes tends to be incomplete for the historical record, the successful adjustment for inhomogeneities requires an objective technique that not only uses any available metadata, but also identifies undocumented change points [Gaffen et al., 2000; Durre et al., 2005]. The PHA of MW09 has these capabilities and thus was used here. Although originally developed for homogenizing time series of monthly mean surface temperature, this neighbor-based procedure was designed such that it can be applied to other variables, recognizing that its effectiveness depends on the relative magnitudes of change points compared to the spatial and temporal variability of the variable.

As can be seen from Table 1, change points were identified in 56% of the 0000 UTC and 52% of the 1200 UTC records, for a total of 509 change points in 317 time series.

Of these, 42% occurred around the time of a known metadata event, while the remaining 58% were considered to be ‘‘undocumented’’ relative to the IGRA station history information. On the basis of the visual inspection, it appears that the PHA has a 96% success rate at detecting obvious discontinuities. The algorithm can be effective even when a particular step change is present at the target and a number of its neighbors simultaneously.

In Japan, for instance, a significant drop in PW associated with a change between Meisei radiosondes around 1981 (Figure 1, top) was detected in 16 out of 17 cases, thanks to the inclusion of stations from adjacent tries in the pairwise comparisons Furthermore, when an adjustment is made around the time of a documented change in radiosonde type, its sign tends to agree with that expected from the known biases of the relevant instruments. For example, the decrease in PW at Yap in 1995 (Figure 1, middle) is consistent with the artificial drying expected from the change from a VIZ B to a Vaisala RS80–56 radiosonde that is known to have occurred at this location and time [Elliott et al., 2002; Wang and Zhang, 2008].

Read Full Post »