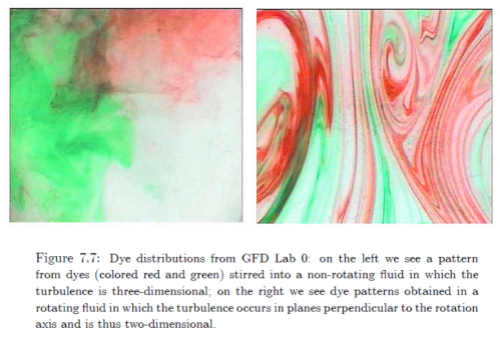

Here is an article from Leonard Weinstein. (It has also been posted in slightly different form at The Air Vent).

Readers who have been around for a while will remember the interesting discussion Convection, Venus, Thought Experiments and Tall Rooms Full of Gas – A Discussion in which myself, Arthur Smith and Leonard all put forward a point of view on a challenging topic.

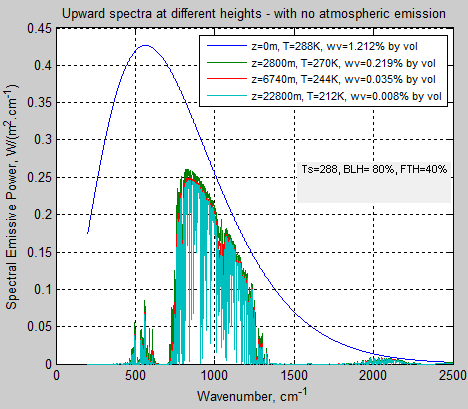

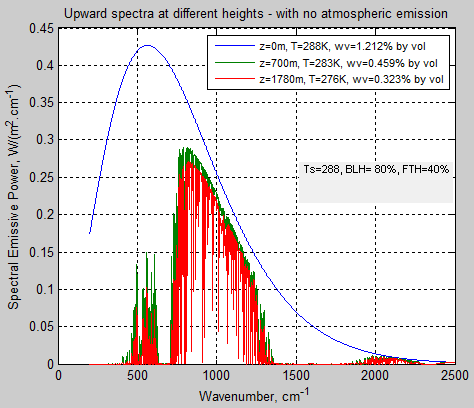

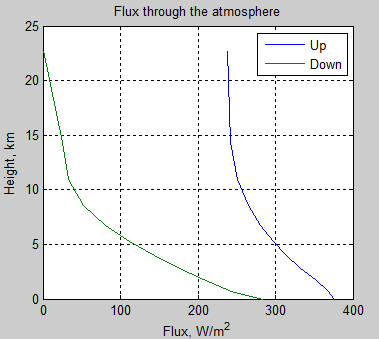

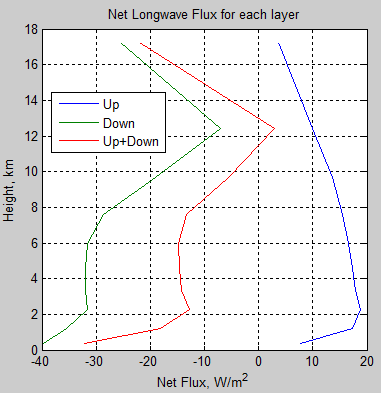

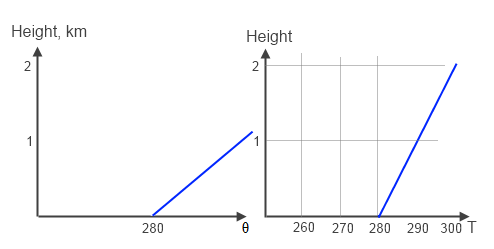

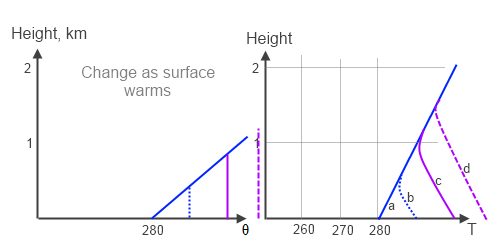

With this article, first I post Leonard’s article (plus some graphics I added for illustration), then my comments and finally Leonard’s response to my comments.

Why Back-Radiation is not a Source of Surface Heating

Leonard Weinstein, July 18, 2012

The argument is frequently made that back radiation from optically absorbing gases heats a surface more than it would be heated without back radiation, and this is the basis of the so-called Greenhouse Effect on Earth.

The first thing that has to be made clear is that a suitably radiation absorbing and radiating atmosphere does radiate energy out based on its temperature, and some of this radiation does go downward, where it is absorbed by the surface (i.e., there is back radiation, and it does transfer energy to the surface). However, heat (which is the net transfer of energy, not the individual transfers) is only transferred down if the ground is cooler than the atmosphere, and this applies to all forms of heat transfer.

While it is true that the atmosphere containing suitably optically absorbing gases is warmer than the local surface in some special cases, on average the surface is warmer than the integrated atmosphere effect contributing to back radiation, and so average heat transfer is from the surface up. The misunderstanding of the distinction between energy transfer, and heat transfer (net energy transfer) seems to be the cause of much of the confusion about back radiation effects.

Simplest Model

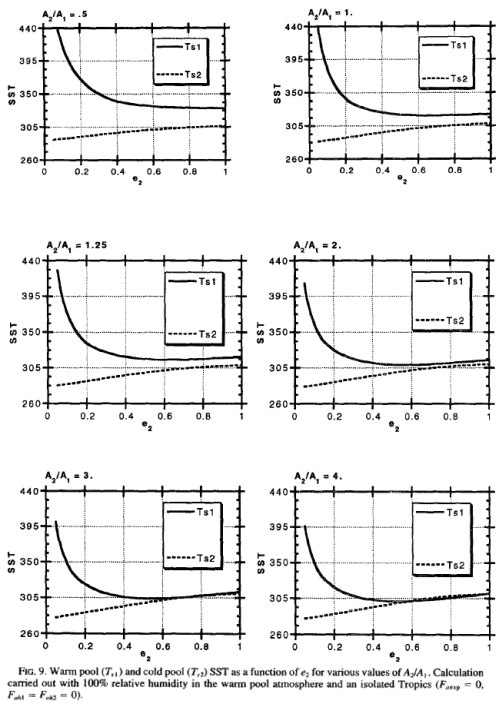

Before going on with the back radiation argument, first examine a few ideal heat transfer examples, which emphasize what is trying to be shown. These include an internally uniformly heated ball with either a thermally insulated surface or a radiation-shielded surface. The ball is placed in space, with distant temperatures near absolute zero, and zero gravity. Assume all emissivity and absorption coefficients for the following examples are 1 for simplicity.

The bare ball surface temperature at equilibrium is found from the balance of input energy into the ball and radiated energy to the external wall:

To = (P/σ)0.25 ….(1)

Where To (K) is absolute temperature, P (Wm-2) is input power per area of the ball, and σ = 5.67×10-8 (Wm-2T-4) is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant.

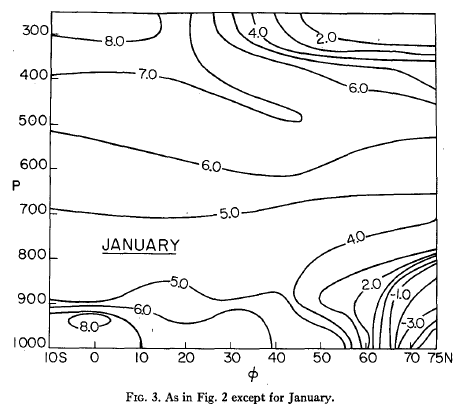

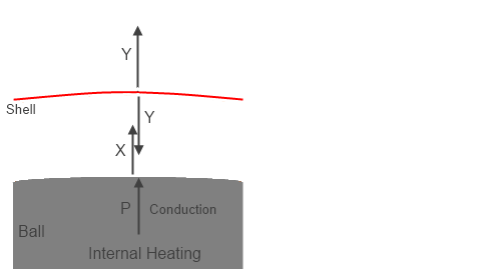

Ball with Insulation Layer

Now consider the same case with a relatively thin layer (compared to the size of the ball) of thermally insulating material coated directly onto the surface of the ball. Assume the insulator material is opaque to radiation, so that the only heat transfer is by conduction. The energy generated by input power heats the surface of the ball, and this energy is conducted to the external surface of the insulator, where the energy is radiated away from the surface. The assumption of a thin insulation layer implies the total surface area is about the same as the initial ball area.

Figure 1 – Ball with Insulation

The temperature of the external surface then has to be the same (=To ) as the bare ball was, to balance power in and radiated energy out. However, in order to transmit the energy from the surface of the ball to the external surface of the insulator there had to be a temperature gradient through the insulation layer based on the conductivity of the insulator and thickness of the insulation layer.

For the simplified case described, Fourier’s conduction law gives:

qx=-k(dT/dx) ….(2)

where qx (Wm-2) is the local heat transfer, k (Wm-1T-1) is the conductivity, and x is distance outward of the insulator from the surface of the ball. The equilibrium case is a linear temperature variation, so we can substitute ΔT/h for dT/dx, where h is the insulator thickness, and ΔT is the temperature difference between outer surface of insulator and surface of ball (temperature decreasing outward).

Now qx has to be the same as P, so from (2):

ΔT = (To-T’) = -Ph/k ….(3)

Where T’ is the ball surface temperature under the insulation, and thus we get:

T’ = (Ph/k)+To ….(4)

The new ball surface temperature is now found by combining (1) + (4):

T’ = (Ph/k)+(P/σ)0.25 ….(5)

The point to all of the above is that the surface of the ball was made hotter for the same input energy to the ball by adding the insulation layer. The increased temperature did not come from the insulation heating the surface, it came from the reduced rate of surface energy removal at the initial temperature (thermal resistance), and thus the internal surface temperature had to increase to transmit the required power.

There was no added heat and no back heat transfer!

Ball with Shell & Conducting Gas

An alternate version of the insulated surface can be found by adding a thin conducting enclosing shell spaced a small distance from the wall of the ball, and filling the gap with a highly optically absorbing dense gas. Assume the gas is completely opaque to the thermal wavelengths at very short distances, so that he heat transfer would be totally dominated by diffusion (no convection, since zero gravity).

The result would be exactly the same as the solid insulation case with the correct thermal conductivity, k, used (derived from the diffusion equations).

It should be noted that the gas molecules have a range of speeds, even at a specific temperature (Maxwell distribution). The heat is transferred only by molecular collisions with the wall for this case. Now the variation in speed of the molecules, even at a single temperature, assures that some of the molecules hitting the ball wall will have higher energy going in that leaving the wall. Likewise, some of the molecules hitting the outer shell will have lower speeds than when they leave inward. That is, some energy is transmitted from the colder outer wall to the gas, and some energy is transmitted from the gas to the hotter ball wall. However, when all collisions are included, the net effect is that the ball transfers heat (=P) to the outer shell, which then radiates P to space.

Again, the gas layer did not result in the ball surface heating any more than for the solid insulation case. It resulted in heating due to the resistance to heat transfer at the lower temperature, and thus resulted in the temperature of the ball increasing. The fact that energy transferred both ways is not a cause of the heating.

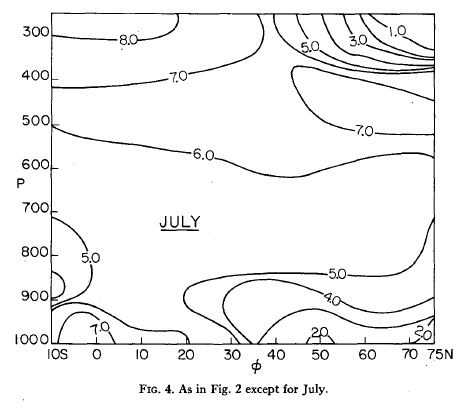

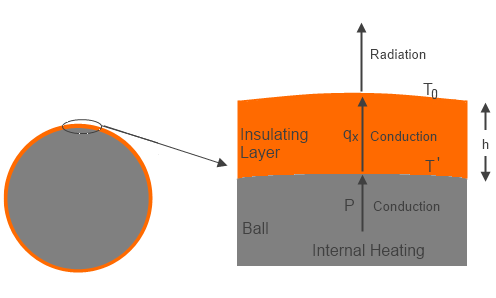

Ball with Shell & Vacuum

Next we look at the bare ball, but with an enclosure of a very small thickness conductor placed a small distance above the entire surface of the ball (so the surface area of the enclosure is still essentially the same as for the bare ball), but with a high vacuum between the surface of the ball and the enclosed layer.

Now only radiation heat transfer can occur in the system. The ball is heated with the same power as before, and radiates, but the enclosure layer absorbs all of the emitted radiation from the ball. The absorbed energy heats the enclosure wall up until it radiated outward the full input power P.

The final temperature of the enclosure wall now is To, the same as the value in equation (1).

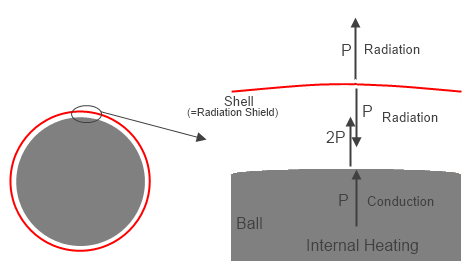

Figure 2 – Ball with Radiation Shield separated by vacuum

However, it is also radiating inward at the same power P. Since the only energy absorbed by the enclosure is that radiated by the ball, the ball has to radiate 2P to get the net transmitted power out to equal P. Since the only input power is P, the other P was absorbed energy from the enclosure. Does this mean the enclosure is heating the ball with back radiation? NO. Heat transfer is NET energy transfer, and the ball is radiating 2P, but absorbing P, so is radiating a NET radiation heat transfer of P. This type of effect is shown in radiation equations by:

Pnet = σ(Thot4-Tcold4) ….(6)

That is, the net radiation heat transfer is determined by both the emitting and absorbing surfaces. There is radiation energy both ways, but the radiation heat transfer is one way.

This is not heating by back radiation, but is commonly also considered a radiation resistance effect.

There is initially a decrease in net radiation heat transfer forcing the temperature to adjust to a new level for a given power transfer level. This is directly analogous to the thermal insulation effect on the ball, where radiation is not even a factor between the ball and insulator, or the opaque gas in the enclosed layer, where there is no radiation transfer, but some energy is transmitted both ways, and net energy (heat transfer) is only outward. The hotter surface of the ball is due to a resistance to direct radiation to space in all of these cases.

Ball with Multiple Shells

If a large number of concentric radiation enclosures were used (still assuming the total exit area is close to the same for simplicity), the ball temperature would get even hotter. In fact, each layer inward would have to radiate a net P outward to transfer the power from the ball to the external final radiator. For N layers, this means that the ball surface would have to radiate:

P’ = (N+1)Po ….(7)

Now from (1), this means the relative ball surface temperature would increase by:

T’/To = (N+1)0.25 ….(8)

Some example are shown to give an idea how the number of layers changes relative absolute temperature:

N T’/To

——————-

1 1.19

10 1.82

100 3.16

Change in N clearly has a large effect, but the relationship is a semi-log like effect.

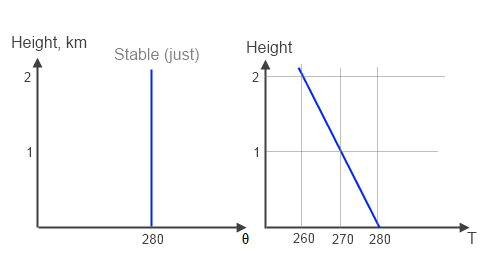

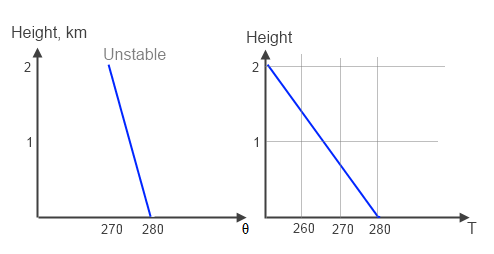

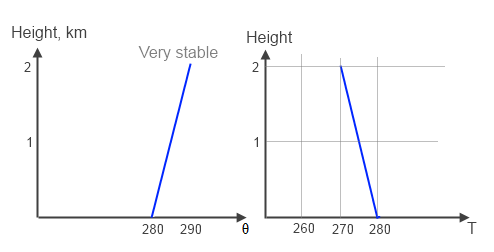

Lapse Rate Effect

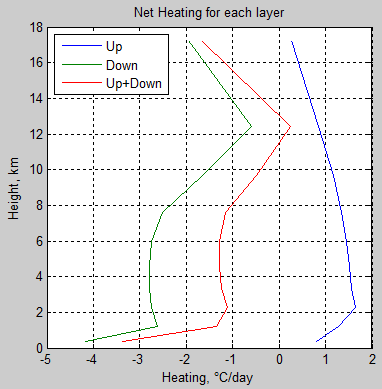

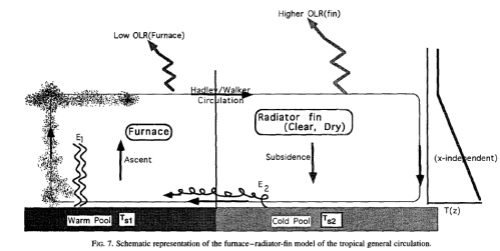

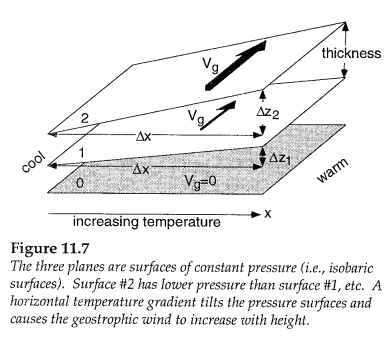

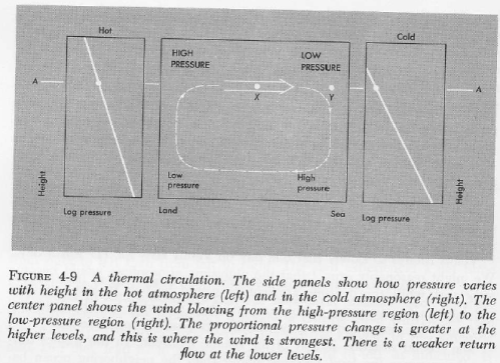

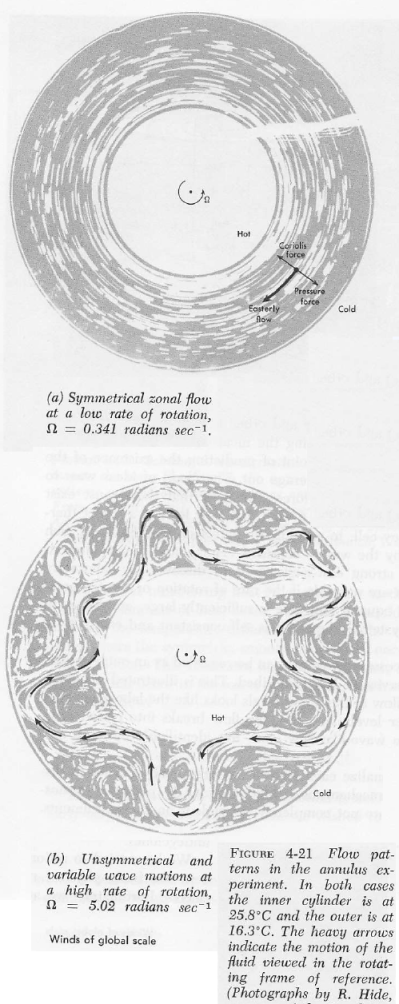

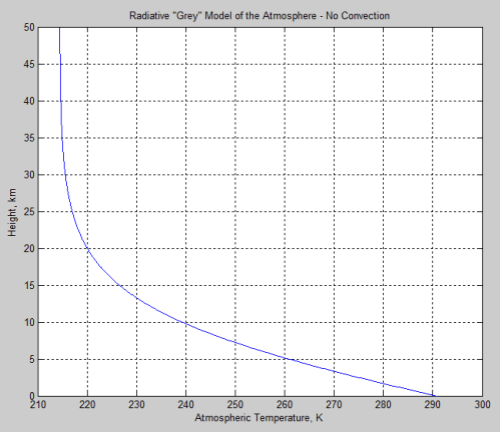

Planetary atmospheres are much more complex than either a simple conduction insulating layer or radiation insulation layer or multiple layers. This is due to the presence of several mechanisms to transport energy that was absorbed from the Sun, either at the surface or directly in the atmosphere, up through the atmosphere, and also due to the effect called the lapse rate.

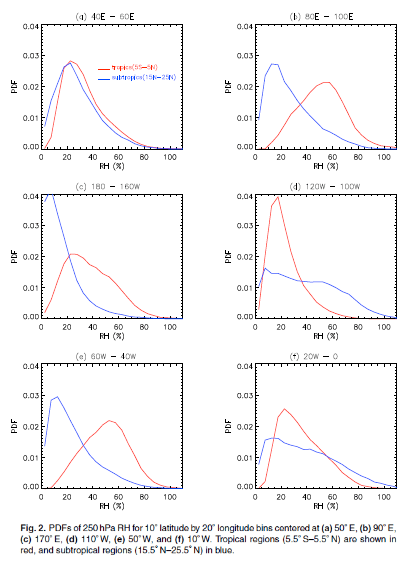

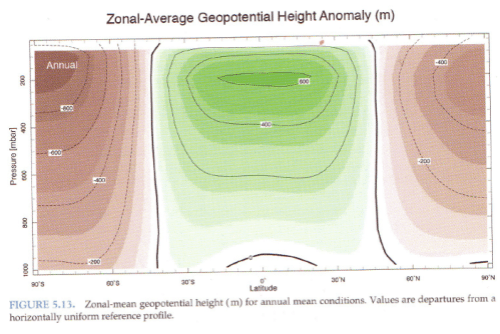

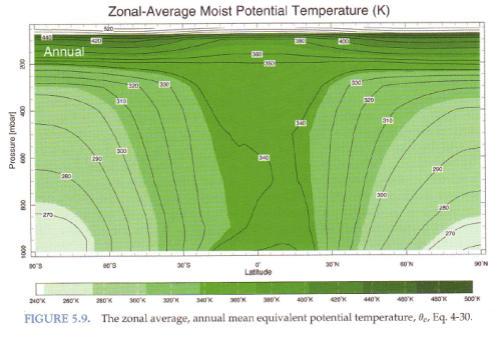

The lapse rate results from the convective mixing of the atmosphere combined with the adiabatic cooling due to expansion at decreasing pressure with increasing altitude. The lapse rate depends on the specific heat of the atmospheric gases, gravity, and by any latent heat release, and may be affected by local temperature variations due to radiation from the surface directly to space. The simple theoretical value of that variation in a dry adiabatic atmosphere is about -9.8 C per km altitude on Earth. The effect of water evaporation and partial condensation at altitude, drops the size of this average to about -6.5 C per km, which is the called the environmental lapse rate.

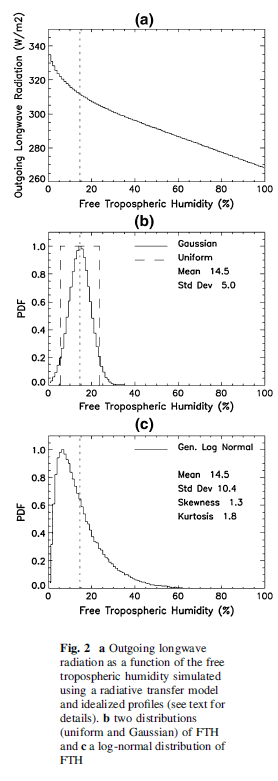

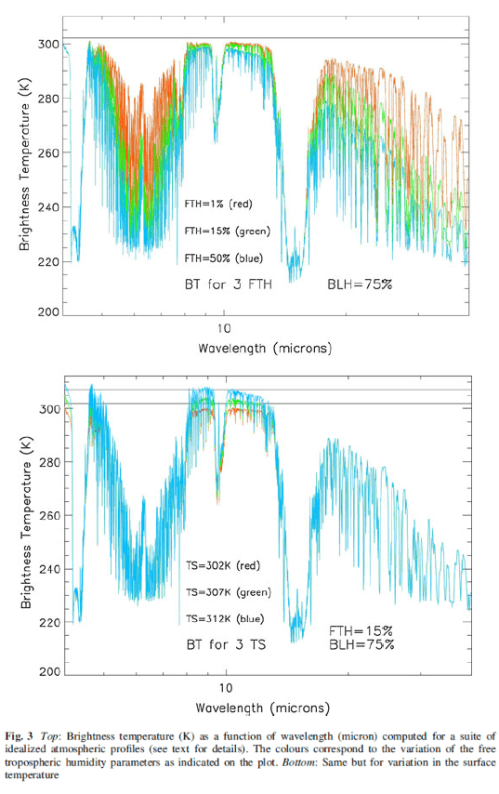

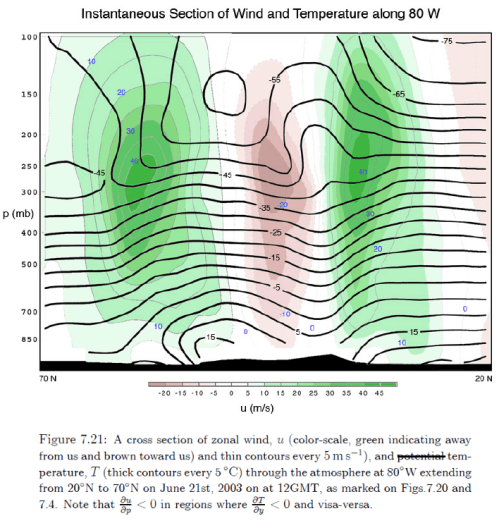

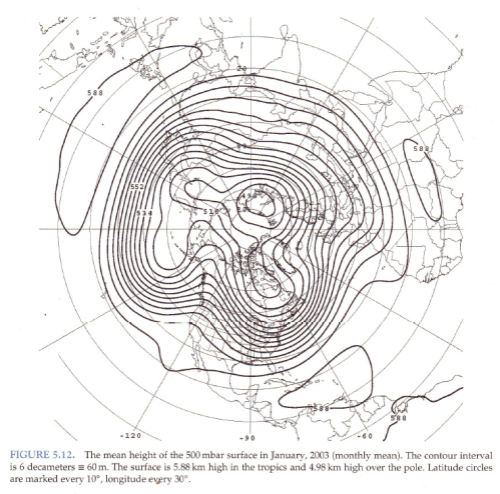

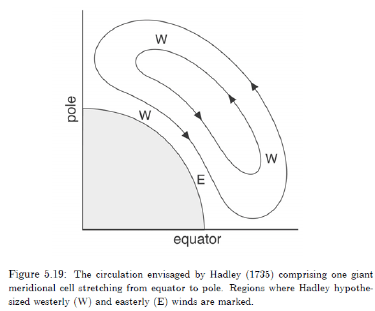

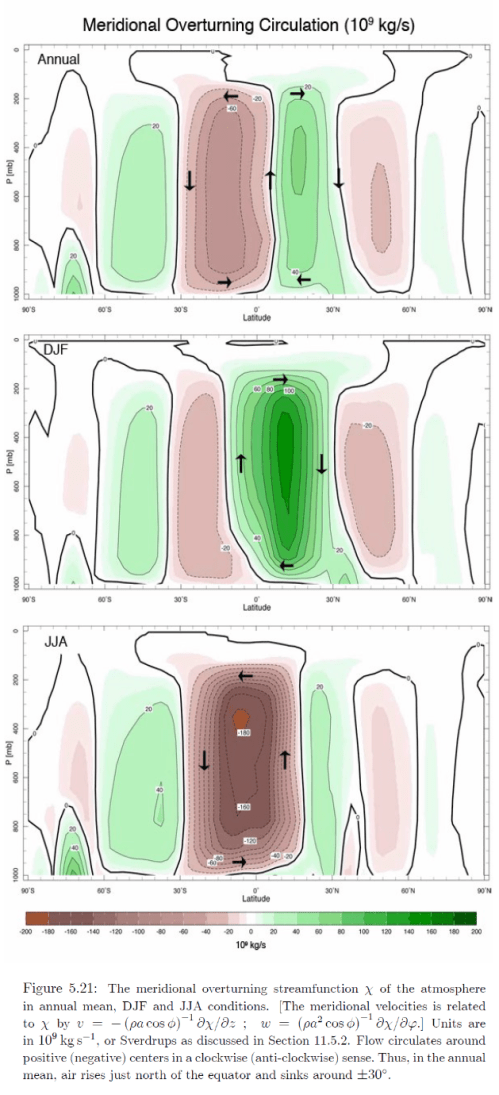

The absorbed solar energy is carried up in the atmosphere by a combination of evapotransporation followed by condensation, thermal convection and radiation (including direct radiation to space, and absorbed and emitted atmospheric radiation). Eventually the conducted, convected, and radiated energy reaches high enough in the atmosphere where it radiates directly to space. This does require absorbing and radiating gases and/or clouds. The sum of all the energy radiated to space from the different altitudes has to equal the absorbed solar energy for the equilibrium case.

The key point is that the outgoing radiation average location is raised significantly above the surface. A single average altitude for outgoing radiation generally is used to replace the outgoing radiation altitude range. The temperature of the atmosphere at this average altitude then is calculated by matching the outgoing radiation to the absorbed solar radiation. The environmental lapse rate, combined with the temperature at the average altitude required to balance incoming and outgoing energy, allows the surface temperature to be then calculated.

The equation for the effect is:

T’ = To -ΓH ….(9)

Where To is the average surface temperature for the non-absorbing atmospheric gases case, with all radiation to space directly from the surface, Γ is the lapse rate (negative as shown), and H is the effective average altitude of outgoing radiation to space. The combined methods that transport energy up so that it radiated to space, are variations of energy transport resistance compared to direct radiation from the surface. In the end, the only factors that raise ground temperature to be higher than the case with no greenhouse gas is the increase in average altitude of outgoing radiation and the lapse rate. That is all there is to the so-called greenhouse effect. If the lapse rate or albedo is changed by addition of specific gases, this is a separate effect, and is not included here.

The case of Venus is a clear example of this effect. The average altitude where radiation to space occurs is about 50 km. The average lapse rate on Venus is about 9 C per km. The surface temperature increase over the case with the same albedo and absorbed insolation but no absorbing or cloud blocking gases, would be about 450 C, so the lapse rate fully explains the increase in temperature.

It is not directly due to the pressure or density alone of the atmosphere, but the resulting increase in altitude of outgoing radiation to space. Changing CO2 concentration (or other absorbing gases) might change the outgoing altitude, but that altitude change would be the only cause of a change in surface temperature, with the lapse rate times the new altitude as the increase in temperature over the case with no absorbing gases.

One point to note is that the net energy transfer (from combined radiation and other transport means) from the surface or from a location in the atmosphere where solar energy was absorbed is always exactly the same whatever the local temperature. For example, the hot surface of Venus radiated up (a very short distance) over 16 kWm-2. However, the total energy transfer up is just the order of absorbed solar energy, or about 17 Wm-2, and some of the energy carried up is by conduction and convection. Thus the net radiation heat transfer is <17 Wm-2, and thus back radiation has to be almost exactly the same as radiation up. The back radiation is not heating the surface; the thermal heat transfer resistance from all causes, including that resulting from back radiation reducing net radiation, results in the excess heating.

In the end, it does not matter what the cause of resistance to heat transfer is. The total energy balance and thermal heat transfer resistance defines the process. For planets with enough atmosphere, the lapse rate defines the lower atmosphere temperature gradient, and if the lapse rate is not changed, the distance the location of outgoing radiation is moved up by addition of absorbing gases determines the increase in temperature effect. It should be clear the back radiation did not do the heating; it is a result of the effect, not the cause.

—— End of section 1 ——

My Response

I agree with Leonard. Now for his rebuttal..

Ok, a few words of clarification. I agree with Leonard about the greenhouse mechanism, the physics and the maths but see a semantic issue about back radiation. It’s always possible it’s a point of substance disguised as a semantic issue but I think that is unlikely.

A large number of people are unhappy about climate science basics but are unencumbered by any knowledge of radiative heat transfer theory as taught in heat transfer textbooks. This group of people claim that back radiation has no effect on the surface temperature. I’ll call them Group Zero. Because of this entertaining and passionate group of people I have spent much time explaining back radiation and physics basics. Perhaps this has led others to the idea that I have a different idea about the mechanism of the inappropriately-named “greenhouse” effect.

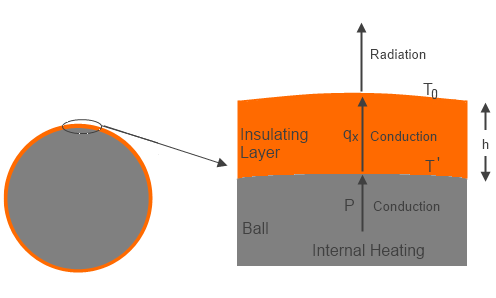

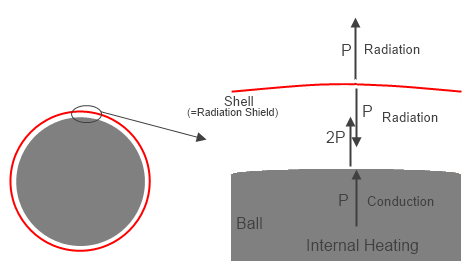

Group Zero are saying something completely different from Leonard. Here’s my graphic of Leonard’s explanation from one of his simplified scenarios:

Figure 2 – again

From the maths it is clear that the downward radiation from the shell (shield) is absorbed by the surface and re-emitted. Here the usual graphic presented by the Group Zero position, replete with all necessary equations:

Figure 3 – how can you argue with this?

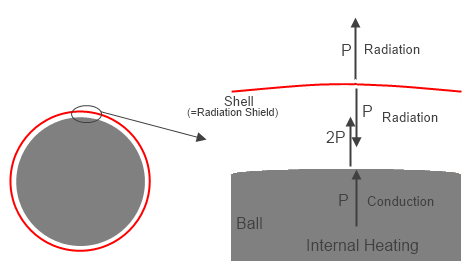

And here’s an interpretation of a Group Zero concept, pieced together by me from many happy hours of fruitless discussion:

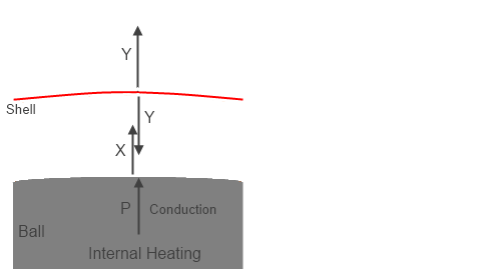

Figure 4 – Group Z?

In this case P, the internal heating, is still a known value. But Y and X are unknown, which is why I have changed them from the solution values shown in figure 2.

Now we have to figure out what they are. Let’s make the assumption that the shell radiates equally inwards and outwards, which is true if it is thin (and so upper and lower surfaces will be at the same temperature) and has the same emissivity both sides. That is why we see the upward flux and the downward flux from the shell both = Y.

Because, according to Group Zero, the downward radiation from a colder atmosphere cannot “have any effect on” the surface, I’m going to assume their same approach to the radiation shield (the “shell”). So the surface only has the energy source P. Group Zero never really explain what happens to Y when it “reaches the ground” but that’s another story. (Although it would be quite interesting to find out along with an equation).

So at the surface, energy in = energy out.

P=X ….(10)

And at the shell, energy in = energy out.

X = 2Y ….(11)

In figure 2, by using real physics we see that the surface emission of radiation by the ball = 2P. This means the surface temperature, T’ = (2P/σ)0.25.

In figure 4, by using invented physics we see that the surface emission of radiation by the ball = P. This means the surface temperature, T'(invented) = (P/σ)0.25.

So the real surface temperature, T’ is 1.19 times larger than T'(invented). Because 20.25 = 1.19.

And back to the important point about the “greenhouse” effect. Because the atmosphere is quite opaque to radiation due to radiatively-active gases like water vapor and CO2 the emission of radiation to space from the climate system is from some altitude. And because temperature reduces with height due to other physics the surface must be warmer than the effective radiating point of the atmosphere. This means the surface temperature of the earth is higher than it would be if there were no radiatively-active gases. (The actual maths of the complete explanation takes up a lot more room than this paragraph). This means I completely agree with Leonard about the “greenhouse” effect.

If back radiation were not absorbed by the surface lots of climate effects would be different because the laws of physics would be different. I’m pretty sure that Leonard completely agrees with me on this.

—— End of section 2 ——

Leonard’s Final Comment

I think we are getting very close to agreement on most of the discussion, but I still sense a bit of disagreement to my basic point. However, this seems to be mainly based on difference in semantics, not the logic of the physics. The frequent use of the statement of heat being transferred from the cold to hot surface (like in back radiation), is the main source of the misuse of a term. Energy can be transferred both ways, but heat transfer has a specific meaning. An example of a version of the second law of thermodynamics, which defines limitations in heat transfer, is from the German scientist Rudolf Clausius, who laid the foundation for the second law of thermodynamics in 1850 by examining the relation between heat transfer and work. His formulation of the second law, which was published in German in 1854, may be stated as: “No process is possible whose sole result is the transfer of heat from a body of lower temperature to a body of higher temperature.”

The specific fact of back radiation and resulting energy transfer does result in the lower surface of the cases with radiation resistance going to a higher temperature. However, this is not due to heat being transferred by back radiation, but by the internal supplied power driving the wall to a higher temperature to transfer the same power. The examples of the solid insulation and opaque gas do exactly the same thing, and back heat transfer or even back energy transport is not the cause of the wall going to the higher temperature for those cases. There is no need to invoke a different effect that heat transfer resistance for the radiation case.

An example can give some insight on how small radiation heat transfer can be even in the presence of huge forward and back radiation effects. For this example we use an example with surface temperature like that found on Venus.

Choose a ball with a small gap with a vacuum, followed by an insulation layer large enough to cause a large temperature variation. The internal surface power to be radiated then conducted out is 17 Wm-2 (similar to absorbed solar surface heating on Venus). The insulation layer is selected thick enough and low enough thermal conductivity so that the bottom of the insulation the wall is 723K (similar to the surface temperature on Venus). The outside insulation surface would only be at 131.6K for this case.

The question is: what is the surface temperature of the ball under the gap?

From my equation (6), the surface of the ball would be 723.2K. The radiation gap caused an increase in surface temperature of 0.2K, which is only 0.033% of the temperature increase. The radiation from the surface of the ball had increased from 17 Wm-2 (for no insulation) to 15,510 Wm-2 due to the combined radiation gap and insulation, and back radiation to the ball is 15,503 Wm-2. This resulted in the net 17 Wm-2 heat transfer. However, the only source of the net energy causing the final wall temperature was the resistance to heat transfer causing the supplied 17 Wm-2 to continually raise the wall temperature until the net out was 17 Wm-2. Nowhere did the back radiation add net energy to the ball wall, even though the back radiation absorbed was huge.

Read Full Post »